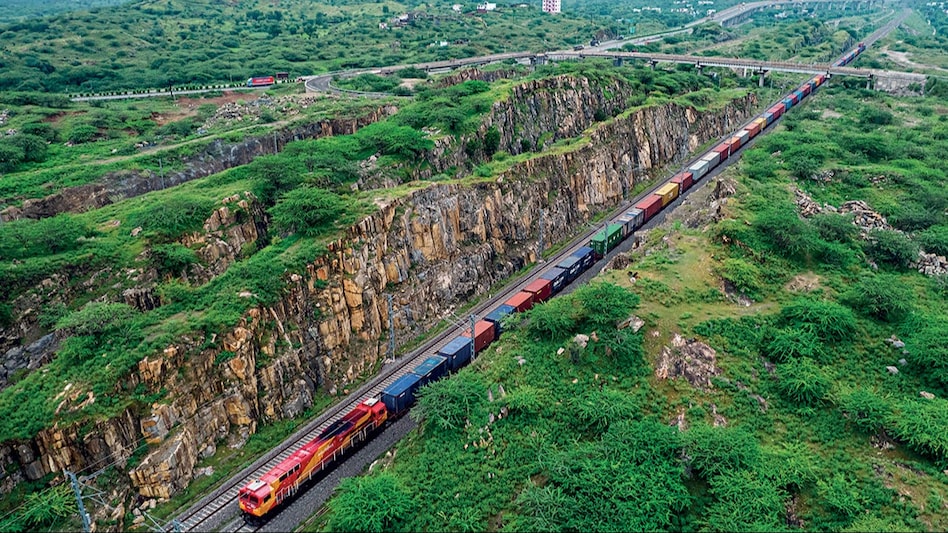

Here's why the Indian Railways' dedicated freight corridors could prove to be a game changer

The dedicated freight corridors (DFC) network of the Indian Railways has started attracting more freight players. From connecting major ports to criss-crossing multimodal logistics parks, DFCs are set to be a game changer for freight services in India

- May 27, 2024,

- Updated May 27, 2024 5:44 PM IST

The summer began early in 2022. That March was the hottest on record. That sparked a huge jump in power consumption as people relied on their ACs and coolers to beat the heat wave. That meant a higher demand for coal to feed India’s thermal power plants, which account for over 70% of the country’s power generation.

- Unlimited access to Business Today website

- Exclusive insights on Corporate India's working, every quarter

- Access to our special editions, features, and priceless archives

- Get front-seat access to events such as BT Best Banks, Best CEOs and Mindrush

The summer began early in 2022. That March was the hottest on record. That sparked a huge jump in power consumption as people relied on their ACs and coolers to beat the heat wave. That meant a higher demand for coal to feed India’s thermal power plants, which account for over 70% of the country’s power generation.

The jump in demand led to a surge in rail traffic, sparking delays. In fact, the Indian Railways had to cancel over 1,000 passenger trains to facilitate the quick delivery of coal to power plants.

Such instances are set to be a thing of the past, all thanks to the Eastern Dedicated Freight Corridor (DFC). This 1,337-km dedicated rail route for coal movement connects Son Nagar in Bihar to Ludhiana in Punjab, intersecting central, eastern, and northern coalfields and feeding coal to over two dozen thermal plants in the North. Most importantly, it is expected to cut the transit time from coal mines in the East to power plants in the North by 24 hours on average.

“The days of blackouts due to coal shortages because of the inefficiency of Indian Railways are over,” Nanduri Srinivas, former Director of Operations and Business Development of the Dedicated Freight Corridor Corporation of India Ltd (DFCCIL), tells BT. “Some of the power plants in the North have cut down on coal reserve stocking, which has helped in releasing the required operational capital as coal is reaching faster due to the eastern DFC,” adds Srinivas, who retired on December 31, 2023.

The western arm of the DFC, which spans 1,506 km and connects Dadri in Haryana with Mumbai, has reduced the transit time of export and import (EXIM) traffic by almost 50%. This section allowing double stacking of containers—on the Indian Railways routes only single containers are loaded on trains—provides connectivity between the country’s major ports, like Mundra and Pipavav in Gujarat, and the northern hinterlands. The section connecting Jawaharlal Nehru Port (JNPT), Mumbai, is likely to be commissioned by the end of 2024.

Once all the pieces are in place, the DFC—which was born in 2006 with the incorporation of the Indian Railways PSU DFCCIL but picked up pace after the NDA government came to power in 2014—is expected to lead to a shift in the movement of freight. From 2000-01, the share of freight traffic had shifted decisively in favour of road—from 63% in 1990-91, the share of rail dipped to a low of 26% by 2021-22, per the DFCCIL, with a corresponding jump in the road share from 37% in 1990-91 to 74% in 2021-22.

Now, the Railways is looking to increase the share of rail in freight loading to 45% by 2050. To make that happen, it has pumped Rs 1.24 lakh crore into the two DFCs, which are likely to be fully commissioned by the end of 2024.

On the DFC, freight trains run at a maximum speed of 100 kmph, against 75 kmph on the Indian Railways network, where passenger trains get priority. More importantly, the average speed is 45 kmph on both the DFCs, almost double the 25 kmph on the Indian Railways network.

This hasn’t escaped attention. Steadily, the DFCs have started attracting major freight players, with containers and cement loading increasing nearly 50% in FY23, as they facilitated the movement of 7,560 rakes and earned `501 crore, against 5,053 rakes earning Rs 326.44 crore in FY22. However, it dropped 33% in FY24 to 5,654 rakes, with a reduction in cement loading due to heavy rains and other factors. But thanks to an increase in container traffic and the launch of the Truck on Train (ToT) service—where trucks are loaded directly on the train—its revenue touched `693.23 crore, an increase of 38% over the previous year.

Among the services, ToT has found an eager audience in the dairy behemoth Amul, which uses it to send milk to Delhi-NCR. The country’s largest carmaker, Maruti Suzuki India, too, is a client. “It is also used for sending auto components and engineering equipment from Delhi-NCR to western India,” R.K. Jain, Managing Director of DFCCIL, tells BT. “For e-commerce players, special cargo services have been introduced using new modified general coaches. This drastically cuts transit time and saves on fuel and manpower costs for road trucks, resulting in great savings.”

Chintan Dilip Lakhani, Vice President & Sector Head-Corporate Ratings at rating agency ICRA Ltd, says DFCs are expected to decongest an already saturated rail network and help shift freight transport to more efficient rail with improved operational features like higher axle loads, enlarged dimensions, and higher speed. “Efficient usage of the DFC and the development of ancillary infrastructure like warehouses and improved last-mile connectivity remain important for a meaningful shift from roads to railways,” he says.

The Association of Container Train Operators (ACTO), whose members hold permits to run container trains across India, says the DFC has the potential to bring about a 15-20% shift from road to rail.

“There are three things that need redress. First, operational issues with transit: better running, less stabling due to the unavailability of crew, so assets become more efficient. Second is rational pricing of freight, and third is related to flaws in wagons designed for double stacking as the newer container wagons have some technical restrictions on how much load you can double stack which is less than the older ones,” says Manish Puri, President of ACTO.

The DFCCIL's efforts seem to be showing results, though they are modest. In FY23, the proportion of containerised cargo moving through rail increased marginally compared with road. Freight loading across Indian Railways saw a 5% YoY increase to 1,591 million tonnes (MT) in FY24, the highest ever.

One place where the shift is becoming evident is in the Dadri DFC section in Uttar Pradesh, which connects the nearby multimodal logistics hub spread across 823 acres being built at a cost of over `7,000 crore and allows double stacking of containers. It is also at the intersection of the eastern and western DFCs.

About 60-70% of containerised traffic moves between western and northern India, and it is primarily EXIM traffic shipped through major ports like Mundra, Pipavav, and JNPT.

The country’s biggest hauler, Container Corporation of India (Concor), feels that once the DFC connects to JNPT by the end of FY25, there will be a significant shift of cargo from road to rail.

“The rail coefficient (percentage of freight carried by rail over the total availability) will increase from 18% to around 25-30% at JNPT. The JNPT coming on the DFC will be very exciting for us because we are building new terminals,” Concor CMD Sanjay Swarup said during an investor call.

The Mundra and Pipavav ports have already started reaping the benefits of the DFC connection, with an increase in volumes and a reduction in wagon turnaround times.

Subrata Tripathy, CEO of Ports Business at Adani Ports and SEZ Ltd, says the double-stack ratio at Mundra Port has seen a significant jump of around 10%.

“The double-stack ratio has significantly grown from 54% last year to about 63%, and that’s only accruing out of the continuous DFC that has since been connected, both on the main line as well as the subsidiary feeder route (Mundra Port). This gives us an advantage of double stacking as well as the relative distance advantage over the main competitors, Pipavav and JNPT,” Tripathy said during an investor call in February. Both Adani Ports and Concor did not respond to queries sent by BT.

Sanjiv Garg, former MD of Pipavav Railway Corporation Ltd, says the port has also seen faster container movement post-DFC connectivity. “Pipavav port has electric line connectivity with DFC, while Mundra still has single-line diesel connectivity,” he says.

According to logistics players, the DFC has turned out to be great, especially for exporters of retail and lifestyle goods from north India and for importers of goods such as electronics, for whom speed to market is extremely important.

Vikash Agarwal, MD of logistics firm Maersk South Asia, says transit time and reliability are the key differentiators, and the DFC has been a great boon for trade as it offers both speed and reliability.

“We have seen that transit times from the hinterland near the NCR to the ports on the western coast have reduced from 72 hours to 36 hours,” Agarwal tells BT. “Using rail as a mode of transport also helps reduce the carbon footprint, which has become a significantly important aspect for many organisations,” he adds.

To optimise the use of DFCs, the Railways has been looking to diversify its freight basket with non-conventional traffic.

The prime example is Amul using the ToT service, through which it loads milk trucks on rakes at Palanpur in Gujarat that are unloaded 659 km away at Rewari in Haryana. The RoRo (roll-on, roll-off) service has cut milk transportation time to 8-9 hours from 24 hours via road. In FY24, the DFC moved 207 ToT rakes, resulting in earnings of Rs 13.65 crore.

Auto major Maruti Suzuki India has started using this service to send auto components from its plant in Manesar, Haryana, to Gujarat’s Mehsana, reducing transit time by 12 hours. Maruti moved about one-fourth of its auto components through the DFC in FY24. Also on the Railways’ radar is smaller freight. Amazon was the first e-commerce player to leverage DFC on the Rewari-Palanpur route starting mid-2023.

For parcel services, the Railways has been using modified passenger train coaches that were otherwise discarded after use. It is also in talks with other companies like Flipkart and Delhivery.

Nanduri says the Railways needs to adopt the Blue Ocean strategy—or exploit avenues not open today—to increase its earnings. The Railways primarily deals with heavy and long-haul freight like cement, steel, feldspar, fertiliser, and others, but leaves behind a very sizeable amount of parcel freight that goes by road.

“Parcel goods are large in number, and some are very valuable, and the Railways needs to venture into this segment to increase earnings and utilise world-class infrastructure,” he adds.

On the challenge from road in terms of first- and last-mile connectivity, DFCCIL CMD Jain says the corridors are complementing roadways. “Innovative services like ToT are steps in this direction. DFC is also creating Gati Shakti cargo terminals at its stations for ease of freight movement with the help of trucks,” Jain says. The Railways has invited entities to set up private freight terminals and multimodal logistics parks for better synergy with road.

The first train on the DFC between New Bhaupur and New Khurja in Uttar Pradesh was flagged off by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in December 2020. The two arms of the DFC can run a maximum of 120 trains per day in each direction (480 in all). But they are limited right now to around 250–280 based on customer demand. The eastern DFC gets more traffic owing to coal and fertiliser movement, while the western DFC is yet to pick up.

Sanjiv Garg, Secretary General of industry body Chartered Institute of Logistics Transport (CILT), says the Railways should easily be moving 3,000 MT freight annually, but it does just half of that. “DFCCIL was created as a separate entity, but the Railways hasn’t given it the freedom to decide policy measures. You are pricing yourself higher than what the market would have allowed and trying to recover costs from freight by cross-subsidising passenger fares,” he says.

Freight costs remain a key concern for logistics players, and they have been demanding tariff rationalisation to make it more competitive and attract more business. For instance, the Railways charges `1,350 for transporting feldspar of 65 tonnage weight for a distance of 750 km (first and last-mile connectivity still by road). On road, it works out to `1,300 with door-to-door delivery for a similar distance in a truck of 40 tonnes carrying capacity. The Railways has also imposed a 10% busy season charge on freight since October 2023. In the past few years, feldspar has moved to road.

Nanduri explains that for the modal shift the Railways is eyeing, it needs to go out of its way to change tariff. “What we need is a One Wagon, One Tariff policy. The Railways charges freight based on commodity rather than wagon type. For example, sand, clay, feldspar, and cement, all transported in a similar kind of wagon, have separate tariffs. Why not charge per wagon, irrespective of commodity?” asks Nanduri.

Maersk’s Agarwal also puts cost as the decisive factor. He says India is a very cost-sensitive market, and if the cost-benefit is not passed on to customers, they start losing interest, even if it means compromising on the speed or reliability of supply chains.

“The Indian Railways has introduced a busy season surcharge on container traffic, which defeats the purpose of being more cost-efficient,” says Agarwal. “Consolidating volumes through collaboration between rail operators will drive economies of scale, leading to lower operating costs. Further, innovative pricing mechanisms can eliminate traditional weight-slab-based pricing, and punitive charges such as underframe charges (standard maintenance of wagons) must be abolished.”

According to the DFC, pricing, crew availability, and wagons are decided by the Railways. Customers have flagged issues like trains getting delayed at entry and exit points of the Indian Railways system due to crew unavailability. Some DFC stretches have connectivity with the railway network, and that is creating bottlenecks at some places.

ACTO’s Puri explains that about 80% of the freight cost is built into the cost paid to the Railways. “I need to see a benefit in that from the Railways, and I cannot only be happy with my 20% (operational cost), where I can save 1-2% on capital costs or double stacks. That is a very critical aspect of my cost where I am getting zero benefit and therefore the customer is getting zero benefit, and the road will continue to challenge me,” he says.

But nobody is in any doubt that the DFC represents world-class infrastructure and that it will increase rail’s share of freight traffic in the years to come. For now, faster coal movement to ensure continuous power supply looks to be the most tangible benefit of the DFC.

@richajourno