Is it a V? Is it a K? L? U? W? The pattern of India’s economic recovery has got India’s top economists seized in a bizarre game of Alphabet Economics. Meanwhile, there’s another shape that’s threatening to put the recovery into an ‘O’ loop. It’s called Omicron, and it could be a nasty customer

Please rotate your device

We don't support landscape mode yet. Please go back to portrait mode for the best experience

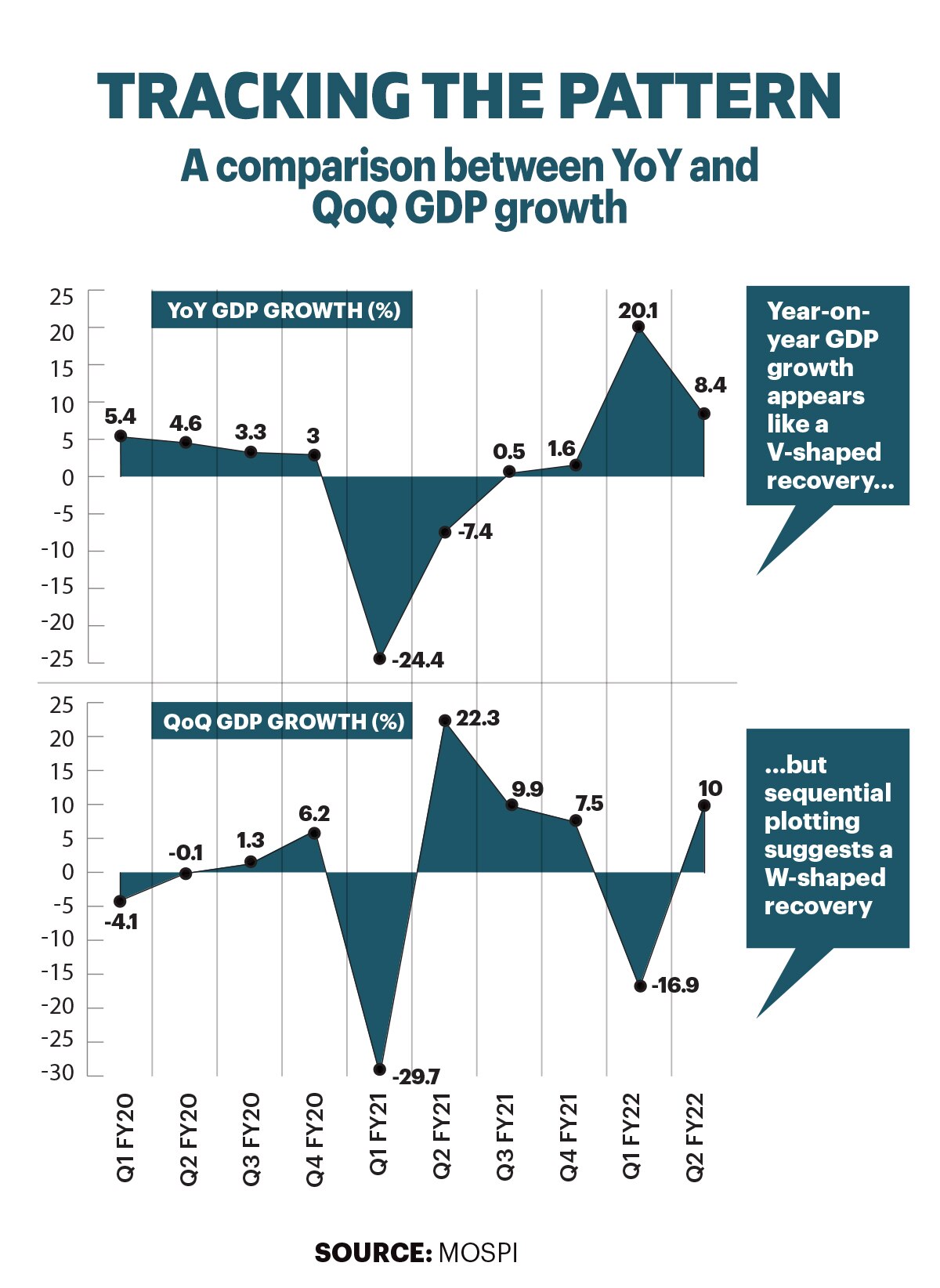

There's a game afoot amongst economists and all and sundry who are engaged in the matter of forecasting economic growth. It's called Alphabet Economics. And it's about predicting the shape of the GDP growth rate curve, after the battering received at the hands of the Covid-19 pandemic. Will it be a V? K? L? U? Or a W? India's former chief economic advisor K.V. Subramanian is betting big on a V-shaped revival, while others including International Monetary Fund (IMF) Chief Economist Gita Gopinath are calling it a K-shaped one, indicating widening inequality or uneven recovery. Even the data indicates two alphabets—V and W (see charts). Plotting sequential quarterly GDP growth shows a W-shaped recovery (with two sharp dips), but plotting annualised GDP growth appears V-shaped, or as N.R. Bhanumurthy, Vice Chancellor of BASE University puts it—a smoking pipe-shaped recovery.

Despite the downside risks from the big O—the Omicron variant of the coronavirus—most economists believe that the worst may actually be behind us. And that Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman's upcoming Union Budget 2022-23 could be an opportunity for the government to take the economy into acceleration mode with a targeted approach for key sectors to boost consumption, which remains weak.

Former chief statistician of India Pronab Sen clearly sees economic recovery taking the K shape, indicating widening disparity between large companies and micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), including the informal segment. Weak demand outlook due to depressed wages and low employment will make the economic recovery rickety going forward, he cautions. "The upward-going tail of the K is corporate India, which is doing very well. The downward part of the K is the rest of India, the non-corporate and non-agriculture sector. That is problematic. The MSMEs are the employment generators and they have suffered the most. Till that sector starts picking up and wages start picking up, the economy is going to remain very fragile," says Sen, who is currently Country Director of International Growth Centre, an economic think-tank.

It is, in fact, a K shape. The upward-going tail of the K is corporate India, which is doing very well. The downward part of the K is the rest of India

Pronab Sen

Country Director

International Growth Centre

The moratorium of six months (March-August 2020) by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) on term loans announced as a Covid-19 response did prevent the death of MSMEs momentarily, but did little to help them survive longer due to a demand slump. "In this five-year period, the corporate sector has taken up a large part of the market share that these MSMEs used to have," says Sen. "Now, getting the MSMEs back is not going to be easy; corporates will fight to protect their turf." Aditi Nayar, Chief Economist at ICRA, who estimates the net loss to the economy between FY21 and FY23 from the pandemic at Rs 39.3 lakh crore in real terms, also sees "a clear K-shaped divergence amongst the formal and informal parts of the economy, and the large gaining at the cost of the small”.

The MSME stress is visible from RBI's data on bank credit as well. The year-on-year gross bank credit growth to micro and small enterprises remained negative at -0.5 per cent in October 2021 for the second straight month following two months of positive growth. This compares with an 8.1 per cent growth in October 2020.

Comparatively, overall gross bank credit was up 6.8 per cent, against 5.1 per cent in October 2021. Even this nearly 7 per cent credit growth is too low for an economy of India's size and growth rate, Reserve Bank of India Governor Shaktikanta Das said recently.

Pradeep Multani, President of trade and industry body PHD Chamber of Commerce and Industry

"It is gathered from the feedback from MSMEs that disruptions caused by the Covid-19 pandemic adversely impacted their earnings by 20-50 per cent, and the micro and small enterprises faced maximum heat, mainly due to reduction in demand and liquidity crunch," says Pradeep Multani, President of trade and industry body PHDCCI (PHD Chamber of Commerce and Industry). In contrast, the aggregate earnings of Nifty companies grew in double digits at 37 per cent year-on-year in the second quarter ended September, with revenues up by 31 per cent. The bigger firms reportedly raised their revenue market shares during the pandemic, either through organic growth or through mergers and acquisitions, as per the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), which is a measure of market concentration to determine market competitiveness.

That Sinking Feeling

RBI Deputy Governor Michael Patra recently said that credit demand was still missing in the economy, largely on account of "the very, very wide output gap", which according to him "will take several years to close". (Output gap or capacity utilisation is the gap between output capacity and actual output.) Patra blamed it on the missing private investment and private demand, which he said is due to the fact that corporates were still facing surplus capacity built over the years. According to RBI data, capacity utilisation at the aggregate level for manufacturing declined to 60 per cent in Q1 of FY22, from 69.4 per cent recorded in the previous quarter. "With capacity utilisation below 70 per cent for the manufacturing sector, there is little reason to invest. Which means the economy is unlikely to get the additional thrust needed from the engines of private consumption and investment," says Dipti Deshpande, Principal Economist, CRISIL.

With manufacturing not producing enough, labour force participation rate (or LPR, share of labour force of the total working-age population) has slumped to nearly 40 per cent compared to 43 per cent before the pandemic, according to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE). "The two pandemic shocks have lowered the LPR structurally… which is the most worrisome," according to the CMIE. Salaried jobs fell by 6.8 million in November, while the number of entrepreneurs declined by 3.5 million. Devendra Pant, Chief Economist at India Ratings, says the falling wage growth and reduced household savings not only impact consumption but also interest rates in the economy. "Unless the household sector revives, it will be difficult for the economy to sustain high economic growth in the medium- to long run," says Pant.

Posting 8.4 per cent growth in the second quarter, the absolute GDP marginally surpassed the pre-Covid-19 level of FY2019-20 by 0.3 per cent in Q2. However, for the first half of 2021-22, the economy was still 4.4 per cent lower than the corresponding period of FY2019-20.

Also, 13 high-frequency indicators show uneven recovery. Seven indicators exceeded pre-Covid-19 levels in October-November 2021, including goods and services tax e-way bill generation (26.7 per cent higher), non-oil exports (26 per cent higher), rail freight traffic (20.2 per cent), Coal India output (15.7 per cent), electricity generation (9.9 per cent), petrol consumption (6.4 per cent), and ports cargo traffic (4 per cent). However, the remaining six indicators were lower than pre-Covid-19 levels. These include scooter production (-25.1 per cent), domestic airline passenger traffic (-22.8 per cent), vehicle registration (-22.8 per cent), diesel consumption (-6.8 per cent), passenger vehicle production (-3.1 per cent) and motorcycle production (-2.6 per cent). "This suggests that the recovery is yet to broad-base," says Nayar of ICRA.

Route to Recovery

Deshpande of CRISIL points out that the bigger impetus to growth will continue to be government investment and exports. "Therefore, the overall pick-up in GDP growth will be gradual, unlike the years when private consumption was the driver. To be sure, as restrictions ease, vaccination rates rise and the economy picks up, private consumption should improve. The pace, however, won't be as much as needed because of ongoing slackness in private consumption," says Deshpande. The private final consumption expenditure, signifying demand in the economy, grew by 8.6 per cent in Q2 year-on-year, but was 3.5 per cent lower than the 2019-20 levels, according to the National Statistical Office (NSO). The public administration, defence and other services component reported a 17.4 per cent growth during the quarter compared to 5.8 per cent in Q1, reflecting an increase in government spending to support economic revival.

We are maintaining our forecast of 9% GDP expansion in FY22, with K-shaped divergence amongst the formal and informal parts of the economy

Aditi Nayar

Chief Economist

ICRA

There are some positive indicators, too. A whopping 83 per cent growth in revenue mop-up in the first seven months of the current fiscal has provided the government significant buffer to spend and support economic revival. Capital expenditure, which acts as a growth multiplier, has grown by 28 per cent in the April to October period, a four-year high. "We expect tax collections to exceed the budget target by around 15 per cent," says an official in the finance ministry, who wished to remain anonymous.

Then, strong exports have held up economic recovery this year. "We expect to reach $400-420 billion [in exports] and, in fact, what has been reassuring is that the order booking position of Indian exporters is pretty good," says Ajay Sahai, Director General and CEO of Federation of All India Export Organisations (FIEO). "That is why we are hopeful that the trend will continue in the next year also."

Ajay Sahai, Director General and CEO of Federation of All India Export Organisations

RBI's bi-monthly consumer confidence survey for the October-November 2021 period showed that demand remained in the "pessimistic terrain". The current situation index, which is current perception compared to the year-ago period, improved to 62.3 in November 2021 from 57.7 in September, after touching a low of 48.6 in July. The rise was largely due to higher consumer spending, but pessimism continued on price levels, employment, economic situation and income. (A reading below 100 denotes pessimism and above 100 indicates optimism.) The index for one-year-ahead expectations rose to 109.6 in November from 107 in September, buoyed by higher optimism for household income and employment scenario.

Threats on the Way

First threat: the big O. Says Pant of India Ratings: "Omicron has added to the list of uncertainties. Delhi has already announced measures limiting mobility, leading to curtailed demand. If this kind of measures are announced by other states and remain in force for a longer time, it will affect consumption and growth in the fourth quarter of the current fiscal." Former chief statistician Sen points out that a lot of the economic recovery will depend on the policy response to Omicron. "The second Covid-19 wave has taught us that if you enforce lockdowns strategically rather than across the board, it is much less disruptive and not all supply chains get locked up," he says.

Many economists agree that MSMEs lost revenue market share to large companies during the pandemic

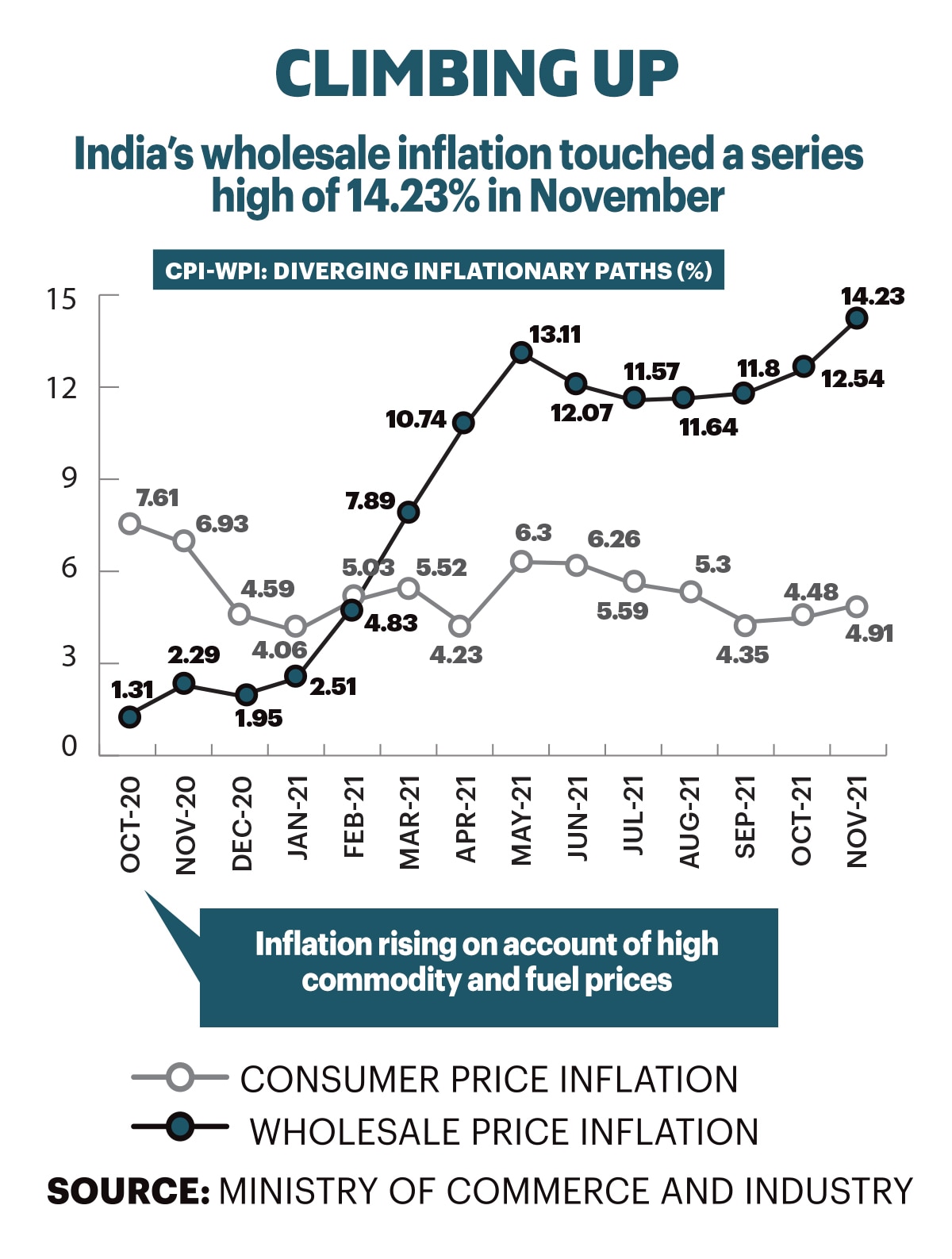

But there are other caveats, too. Inflationary concerns are expected to keep demand muted. India's wholesale inflation touched a series high of 14.23 per cent in November and is expected to remain in double digits for the next few months on account of rupee depreciation, elevated international crude oil prices and, well, Omicron fears-led global supply-chain disruption. Meanwhile, CPI inflation touched a three-month high of 4.91 per cent in the same month. Households expected inflation to harden in the near and medium term, as per the RBI's household inflation expectation survey. The proportion of respondents expecting higher inflation in the next three months and over the year-ahead rose in November 2021. The inflation expectation for the next three months rose by a steep 150 basis points and that for the year-ahead period rose by 170 basis points.

The upcoming Budget is the right time for the government to focus on the medium-term growth targets. They have to bring back the $5-trillion economy discussion

N.R. Bhanumurthy

Vice Chancellor

Dr B.R. Ambedkar School of Economics University

Meanwhile, non-oil, non-gold imports slowed to $31.82 billion in November, down 11 per cent compared to October, indicating slowing domestic demand. Besides, a weaker rupee will only make imports more expensive. The rupee has depreciated by 1.9 per cent in Q3 against the US dollar with central banks globally having started increasing interest rates.

"Given that inflation can be a drag on demand, investment should pick up largely driven by the government. In this context, the slew of infrastructure projects undertaken by the government, notably the Gati Shakti project, inland waterways, textile parks, among others, bode well for India's growth," says Arun Singh, Global Chief Economist, Dun & Bradstreet.

At this point, GDP growth in FY22 is certain, but it's going to be a tough grind. In December, Fitch Ratings cut India's economic growth forecast to 8.4 per cent from 8.7 per cent projected earlier for the current fiscal, saying the rebound after the second wave of Covid-19 infections has been more subdued than expected. Other agencies such as the IMF, Goldman Sachs, and the World Bank also predict 8-9 per cent GDP growth for FY22. And economists such as Pant of India Ratings and Nayar of ICRA expect growth rate of around 9 per cent for FY22.

Consider this. The last five fiscal years have delivered GDP growth rates of 8.26 per cent (FY17), 6.8 per cent (FY18), 6.53 per cent (FY19), 4.04 per cent (FY20), and minus 7.96 per cent (FY21). By that measure, anything between 8 per cent and 9 per cent in FY22 will still be the best in recent times. No matter the shape of the curve.