Faced with the EV conundrum, India’s auto suppliers have devised a dual strategy: Without compromising on their money-making ICE product lines, they are getting a foot in the door by investing in electric too

Please rotate your device

We don't support landscape mode yet. Please go back to portrait mode for the best experience

The 2006 documentary Who killed the electric car? delves into the reasons behind the fall of General Motors' EV1 a few years after its launch in 1996. Wally Rippel, one of the electric vehicle's (EV) designers, pinned the blame on Big Oil's fear of losing their monopoly on transportation fuel. Auto companies were also worried, he continued, about EV development costs in the short term and revenue loss in the longer term as EVs require little to no maintenance. Just 1,100-odd EV1s hit the road before the programme was shelved in 2003.

The EV revolution lay in limbo until Tesla picked up the baton with the launch of the Roadster in 2008. A little over a decade later, Tesla's Model 3 became the best-selling EV of all time, having retailed 6.4 lakh units until August last year. The world is now on the cusp of mass EV adoption. But Rippel's concerns still hold true, especially in India, the fourth-largest auto market in the world.

"It is not going to be a total disruption. For at least 10 years, ICE (internal combustion engine) is not going to disappear," Nirmal K. Minda, Chairman and Managing Director, UNO Minda Group, says bluntly. The numbers bear that out. India's EV component market was worth around $536 million in 2019, according to market research firm P&S Intelligence, and is expected to grow at a CAGR of 22.1 per cent between 2020 and 2030. This, companies say, will come on the back of both ICE vehicles and EVs.

UNO Minda Group and other components makers are, therefore, gearing up to build their EV business, but without compromising on their money-making ICE product lines. Minda Industries Limited (MIL), UNO Minda's flagship firm, recently formed a joint venture (JV) with FRIWO AG, a German manufacturer of power supply units and e-drive solutions, to supply EV components. The Indian firm holds a 50.1 per cent stake in the JV, which has a planned capital expenditure (capex) of `390 crore over the next six years. Similarly, Bharat Forge recently took a stake in UK electric truck manufacturer Tevva Motors for `90 crore. Sundram Fasteners, part of the TVS Group, has already built its EV parts market into a `100-crore business. "The capex cycle has begun and we're investing not just for EVs, but also for ICE because the demand is coming back," says Sunjay Kapur, President, ACMA (Automotive Component Manufacturers Association).

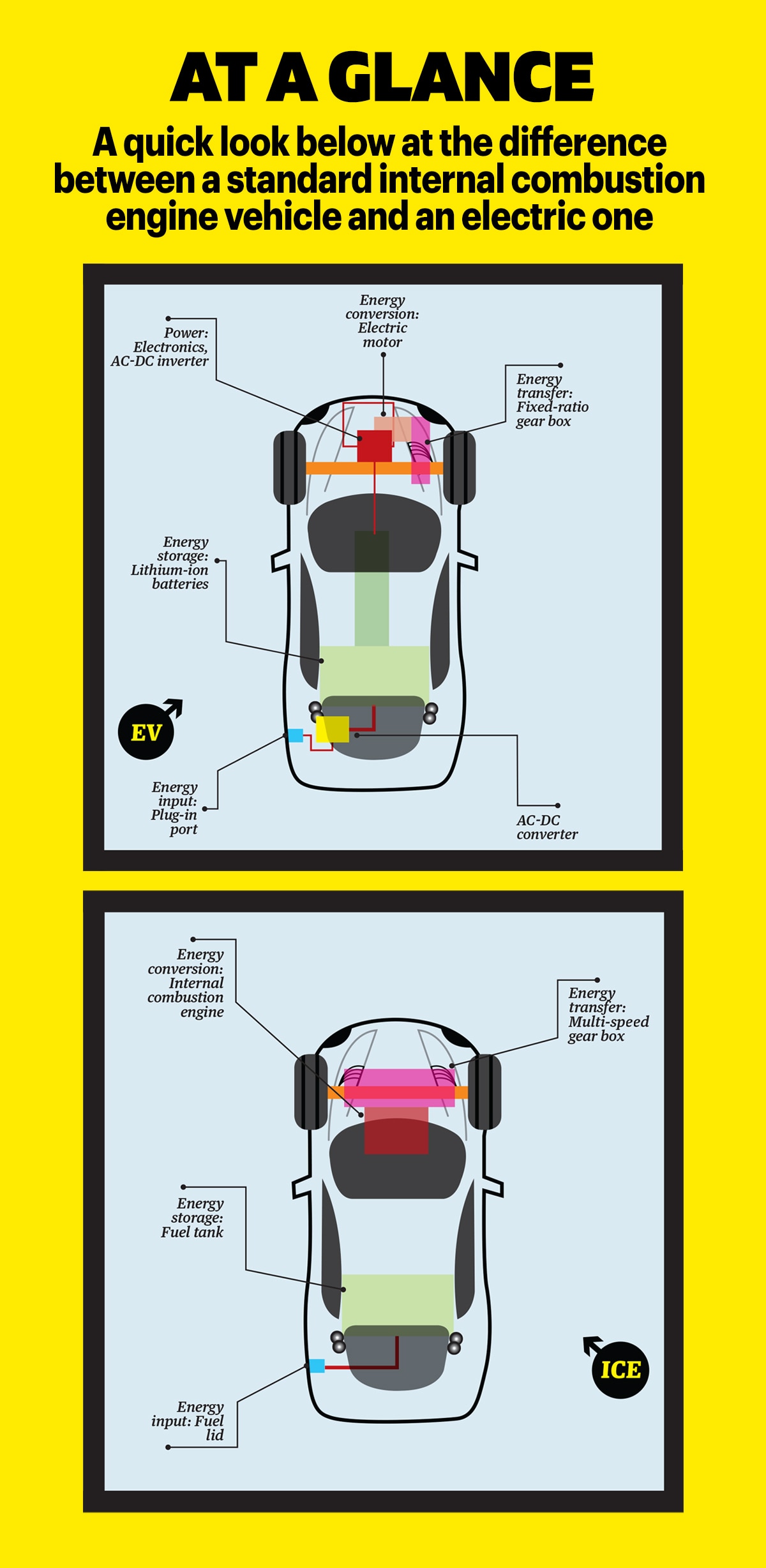

It is worth noticing here that EVs account for less than 1 per cent of automobile sales in India. While charging ecosystem and range anxiety remain key challenges on the consumer side, auto parts makers have a different set of concerns. For one, the shift to EVs could impact the aftermarket revenue by almost 8 per cent by 2025. This is because while an ICE car has 20,000 moving parts, an EV might have around 25, leading to lower upkeep expenses.

Kapur, though, doesn't buy this reasoning. First, he points out that components such as seats, braking and steering systems will largely remain the same. Secondly, he says that as volumes increase over time, so will profitability. "The volumes may be lower today, but they will increase. If the companies are profitable in ICE, they'll be profitable in EV as well. The message is loud and clear: We're moving to EV." As with consumers, he says it's a mindset issue for suppliers. "It's about how rapidly people are willing to adapt to newer technologies or invest in technologies that are relevant. The end goal is to have a clean environment. That's where regulation will come into play."

The government's goal is to completely transition to EVs by 2030. Phase II of the Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Hybrid and Electric Vehicles (FAME) scheme was adopted in 2019, with 86 per cent of the funds set aside for consumer incentives and 10 per cent to build charging infrastructure. States such as Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Maharashtra and Delhi have introduced policies to promote a smooth transition to EVs.

EVs will make components such as clutches, radiators and gears obsolete, component makers fear. They will be, however, replaced with new parts such as electric motors, batteries, inverters and microprocessors. Start-ups will cater to most of this demand from original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) in the nearer term, experts say.

"There are thousands of start-ups both on the technology side, as well as on the two- and three-wheeler OEM side of the business. They will have a high contribution in shaping and making the first bets and moves," says Samir Yajnik, Executive Director, Electra EV. The Ratan Tata-backed firm's powertrains drive more than a quarter of the electric cars on Indian roads, but Yajnik says stronger competition is around the corner. "Bigger OEMs will also come. They are just waiting to see how this builds up.”

It is not going to be a total disruption. For at least 10 years, ICE (internal combustion engine) is not going to disappear

Nirmal K. Minda

Chairman and Managing Director

UNO Minda Group

Indeed, traditional auto suppliers have already started restructuring their businesses to accommodate EVs. UNO Minda created a separate unit for its EV business, Spark Minda Green Mobility System, this year. Its flagship company MIL also reorganised its business into four domains, including one that focusses on electrical and control systems. Both divisions are focussing on the newer products for EVs and allied products such as telematics, says Minda. He plans to grow UNO Minda's EV product portfolio of motor controllers, battery management systems, body control modules and RCD cables (to protect against the risks of electrocution). And they are ready to splash the cash.

"Depending on the volumes, we're estimating around `300-500 crore of investment in the next four-five years," says Minda. The firm is investing to deepen ties with two-wheeler makers such as Bajaj Auto, TVS Motor, Hyundai and Yamaha, as well as start-ups. It also stands to benefit as more automakers look to source parts locally. Minda says the likes of Mahindra, Tata, Maruti, Hyundai and Kia are "investigating our competency and capability.”

The world is seeing software permeate all areas, and the automotive industry is no different. The marriage of hardware and software in vehicles, such as mirrors being replaced by cameras, will only grow stronger, especially in EVs. That, says ACMA's Kapur, is morphing the industry. "Our industry is now a mobility industry and not just limited to automotive components. We're used to this kind of evolution. It's happening at a much quicker pace now and, therefore, we need to continuously invest in R&D and new technologies to stay ahead of the curve.”

More players coming in will start to get the cost structure down, which is dependent on three areas: volumes, technology and battery prices

Chetan Maini

Chairman and Co-founder

SUN Mobility

The modern connected vehicle houses anywhere between hundreds to thousands of microprocessors that both provide on-board diagnostics for the driver, as well as vehicle and component performance data for manufacturers. The use of software in cars could double in the next four years, says K.S. Viswanathan, VP (industry initiatives), NASSCOM. He estimates that software accounted for about 15-20 per cent of the components in earlier automobiles, which has risen to about 30 per cent now. "By 2025, it is expected that 60 per cent of an automobile will be completely software. The change and rate of adoption will never be linear. It is just a question of availability and falling in place of several components of the infrastructure."

But this is a tough transition for traditional auto parts makers to make on their own. So they are partnering with technology companies. "Collaborate or die, that's where we're headed as an industry," says Kapur. For example, Japan's Toyota Motor and Panasonic forged a JV in January 2019 to supply lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries for EVs. Two years before that, Suzuki, Denso and Toshiba formed a JV to build a $180-million plant in Gujarat to produce Li-ion batteries for Suzuki's full-electric and hybrid cars, as well as to supply to others. There are more than 50 companies supplying EV makers today and collaborations are only going to go north.

Electra EV's Yajnik says it is inevitable that traditional players will also start developing in-house software. "We are witnessing a tenfold increase in demand between eight months or one year back and now. Big business houses are talking about setting up their own semiconductor factories. Whether it's happening at a pace which is good enough we don't know yet," he says.

However, in the near term, Yajnik, like most experts, says that battery prices will play the most critical role. Battery prices are expected to fall by more than 30 per cent between 2018 and 2025, according to P&S Intelligence, thus making EVs more affordable. For India's battery makers to stomach that drop, localisation is the key.

Apollo Tyres, being in the business of making one of the most polluting auto parts, wants to focus on its sustainable raw material procurement strategy

Neeraj Kanwar

Vice Chairman and Managing Director

Apollo Tyres

"When it comes to localisation, it's about two things—designing in India and manufacturing in India," says Chetan Maini, Chairman and Co-founder of SUN Mobility, which has placed its bets on battery swapping technology. Maini knows what he's talking about. About 20 years ago, even before Tesla was founded, he launched India's first EV, the Reva. His manufacturing philosophy hasn't changed since. "All our technologies are developed in-house—all electronics, the software, battery manufacturing, etc., except for the cell." The company will install a second production line for batteries by April next year, he adds.

Maini says with more players coming in, there will be an easing of the cost structure, which is dependent on three areas—volumes, technology and battery prices. "While the first two factors are picking up, the third is on the negative side right now, especially in the short term. We're not seeing battery prices go down the way they should. They're going up because the raw material cost is going up significantly," he says. He expects that it will take another 18-24 months for costs to normalise.

SUN Mobility, though, isn't waiting. The Bengaluru-based company has collaborated with the likes of Ashok Leyland, Piaggio Vehicles, Uber India and others to set up battery-swapping stations. In September, it partnered with Zypp Electric, a start-up focussing on last-mile deliveries using EVs, to deploy 10,000 vehicles. A month later, it raised $50 million from Vitol, a Dutch energy trader and investor in renewable energy firms. German auto parts maker Bosch took a 26 per cent stake in SUN last year. The funds, Maini says, help him scale the firm's technology and infrastructure to go global. "Our aspirations are focussed on India today and we are going to be global because we see that our solution is very scalable."

Today, many Indian auto parts makers are exploring opportunities to export products and services to North America, Europe and even China. The idea is to de-risk their businesses by not depending entirely on the domestic market until EVs become mainstream. Exports totalled $13.8 billion this year and ACMA expects this to go up to $45 billion in the next three-five years. "We are looking at supplying to the world. Our aim is to build a manufacturing hub in India for the world," says Kapur. When India switched from BS4 to BS6 emission norms, the Indian auto industry adjusted faster than China's did for its new norms, claims Kapur. But time is not a luxury that India has now, says Minda. "If we don't do it now, it will be late."

Also read: Money Today: Does it Make sense to Invest in EVs?