There's a new genie in town. It's called Buy Now, Pay Later, and it promises to deliver all you need through quick, very short-term, interest-free loans. But this genie comes with significant risks—hidden costs, new to credit population with no credit bureau records, lack of financial literacy in smaller towns, and regulatory gaps. BNPL's value proposition is undeniable, but so is the spectre of consumers getting sucked into uncontrolled spending, and spiralling debt

Please rotate your device

We don't support landscape mode yet. Please go back to portrait mode for the best experience

Is your electric bill lying unpaid? Or perhaps your gas bill? Is your phone recharge due, or cable bill? Is it because you are running a little low on cash or want to spend elsewhere? Well, Freecharge, a Gurugram-based fintech, has you covered with an instant one-month, interest-free loan up to Rs 10,000. Not just for utilities, but similar loans with flexible repayment schemes are also available at the checkout page of an Amazon or a Flipkart, whether you buy an iPhone or a perfume. Ride-hailing firm Ola lets you pay for all trips at once, every 15 days. And in case your holiday plan seems just out of your wallet's reach, travel aggregator MakeMyTrip is ready to finance your tickets and hotel bookings. Just buy now and pay later.

BNPL, as the loan product is popularly called, is the latest financial pied piper, leading the millennial and Gen Z generations as well as borrowers in under-served and unbanked smaller towns into the world of credit. The lyrics accompanying the tune are just as alluring—'dream big, pay small'. And these first-time borrowers are following in hordes as they are, more often than not, denied loans in the traditional banking system since they lack a credit history.

In less than a decade, BNPL has become a global craze, spanning Sweden to Australia and the US to the UK. Unlike traditional bank loans—such as to buy a house or a car, or personal loans—BNPL is a point-of-sale product. The borrower gets the option of an instant, short-term loan with a deferred repayment tenure, including the option for equated monthly instalments (EMIs) after the end of an interest-free period. The allure of BNPL is that, unlike traditional loans, these are small-ticket loans of as low as Rs 3,000 for daily consumption purposes. It's similar to a credit card but without the hassles of an application process, card-swiping infrastructure, and separate limits for purchases and cash withdrawals. Critically, there is scant checking of a borrower's credit bureau score and only a cursory check, if at all, of their income statements before they get the loan. Sometimes in minutes.

Little wonder, then, that BNPL has exploded in popularity in India. The current BNPL market is worth $3-3.5 billion (Rs 22,500-26,250 crore) and is expected to reach an eye-popping $45-50 billion (Rs 3.37-3.75 lakh crore) by 2026, according to consultancy firm RedSeer. At this rate, BNPL is all set to overshadow the traditional credit markets that, after decades of effort, stack up at Rs 8.65 lakh crore for personal loans at banks and Rs 1.23 lakh crore for outstanding credit card debt. The growth thesis is simple. India's credit card population is only 67 million, while banks are content with the top 100 million crème de la crème. In comparison, the current count of 250 million Indians making digital spends on apps and e-commerce portals will rise to 500-600 million in the next three to four years. This is the BNPL target audience. "There is a large population of eligible credit users in the market who have zero credit bureau footprint," says Upasana Taku, COO and Co-founder of MobiKwik, one of India's largest BNPL players.

There is a large population of eligible credit users in the market who have zero credit bureau footprint... We have built our own machine learning sort of proprietary score. This helps us to underwrite which users should be given how much credit

Upasana Taku

COO and Co-founder

MobiKwik

And this potential has birthed a host of BNPL platforms. On the other hand, many existing payment platforms, digital wallet operators and even major e-commerce companies have built a BNPL offering on top of their existing payments business. Now one can get BNPL offers from Paytm Postpaid, MobiKwik, Freecharge, ZestMoney, LazyPay, ePaylater, CapitalFloat, Amazon Pay, among others. Even traditional banks are jumping in. Axis Bank bought Freecharge from e-commerce firm Snapdeal for Rs 385 crore in July 2017.

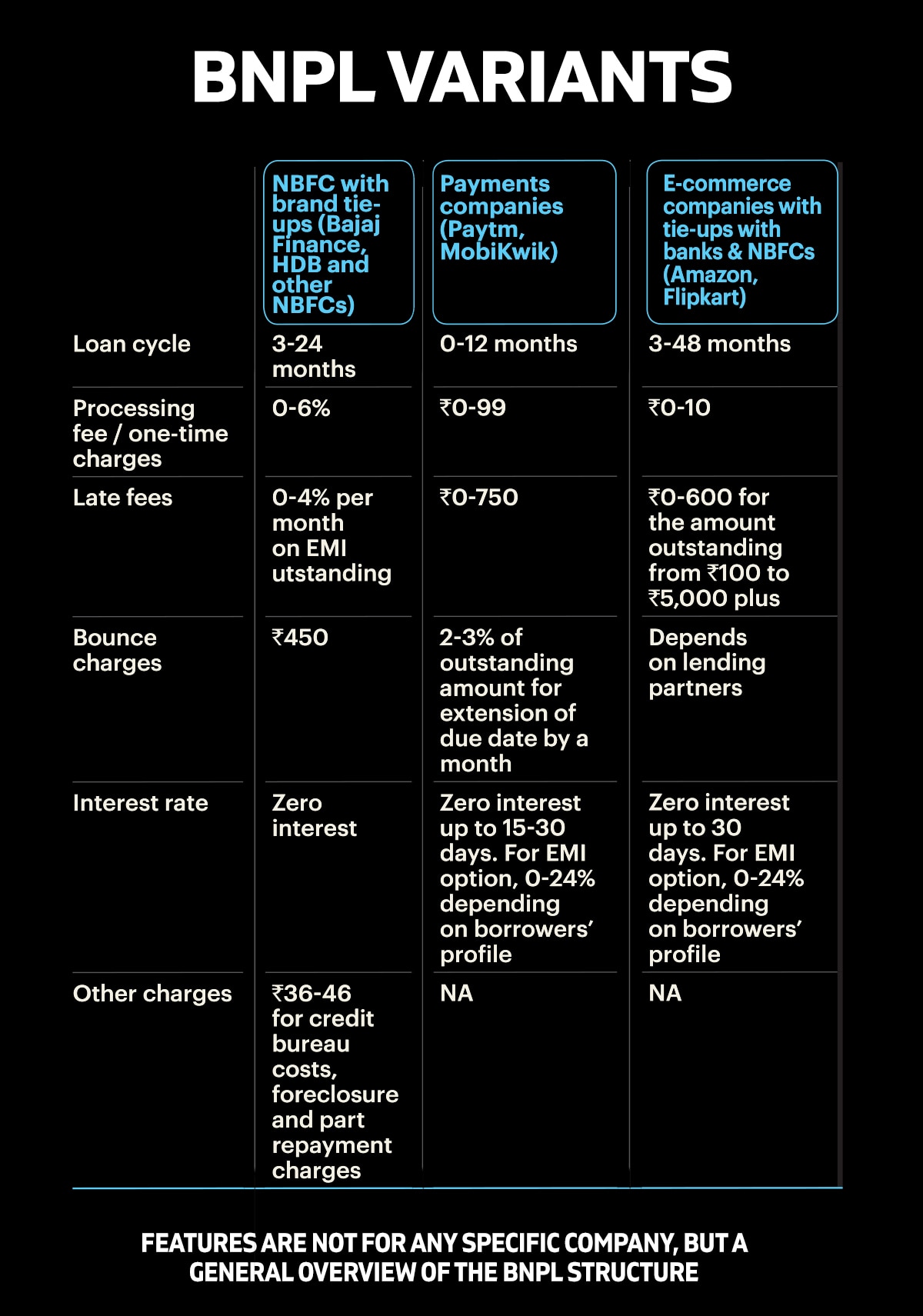

There are a couple of versions of BNPL loans. The first is for small-value transactions such as e-grocery bills and online ticketing. Here, there is no loan per se, but the payment is deferred. There is no interest if the amount is paid on time, but a default attracts penalties and charges. These loans are apt for those who defer payments to salary dates or to tide over in case of a sudden income shortfall. The other form of BNPL is similar to a credit card, with EMIs after an interest-free repayment window of about 30-45 days. This is slightly cheaper than credit cards and fits in with making indulgent or impulsive big-ticket purchases. "The EMI product is focussing on bridging the gap between affordability and aspiration," says Siddharth Mehta, CEO, Freecharge.

Experts suggest that there is no problem with the BNPL product per se but there are several risks that come from hidden costs, lack of disclosures and transparency, and a new-to-credit population with no credit history. The lack of financial literacy in general, and in smaller towns in particular, is harmful to borrowers but advantageous for lenders. "There is no free lunch. If somebody is saying zero per cent, there is someone else who is paying it," says Madhusudanan R., Co-founder and CEO of digital banking infrastructure provider M2P Fintech. Besides, there are several regulatory loopholes such as the lack of data protection laws, as well as lender-side issues such as inadequate collection frameworks.

For now, though, both borrowers and lenders are laughing all the way to the checkout page, enjoying the new-age avatar of an age-old practice.

Bajaj finance pioneered BNPL in 2013 and scaled up to capture 80-90 per cent of the consumer durable financing market. The Pune-based non-banking financial company (NBFC) built the product on the subvention method by partnering with brands that gave discounts and covered zero interest costs, allowing it to offer customers interest-free loans. BNPL, though, predates Bajaj by decades in India where the first form of lending was the local kirana store opening a khata, or bills-due book, for customers buying on credit. In fact, the credit card was the first organised BNPL product.

The concept of using transaction flow to subsidise the cost of credit to give consumers a cheaper credit product, called BNPL, gained popularity in the West over the past 5-7 years, says Lizzie Chapman, CEO and Co-founder of ZestMoney and President of the Digital Lenders Association of India. Bajaj Finance broadened the concept to cross-sell other products, increasing its overall returns from each customer. New-age platforms such as Paytm and BharatPe soon followed suit to make BNPL ubiquitous. "BNPL can also be exercised on top of credit cards. Today, all the credit cards give an option of easy EMIs," says Bhavin Patel. The Co-founder and CEO of LenDenClub, a peer-to-peer lending platform, has another observation, "BNPL is a use case rather than a product."

For a non-salaried customer, there exists much patchier data. You have to use a lot more complexity in your model to make proxies and sort of guess on income and expenditure. But it’s not impossible

Lizzie Chapman

CEO and Co-founder

ZestMoney

This ubiquity is because BNPL is not only the most attractive but also the only option available to first-time borrowers shunned by banks as they have no credit history. Today, more than 50 per cent of the borrowers on BNPL platforms are new to credit. This large population, say industry executives, has an unmet credit need for consumption and discretionary purchases. "We are only catering to their daily use purchases such as grocery and milk and shopping needs," says Amit Kumar, Founder and CEO of GalaxyCard, which offers an instantly approved smartphone-linked credit card.

In fact, BNPL players underwrite new borrowers based on their payment history, whether they be for e-shopping or even utility bills. These platforms have proprietary models to assess an applicant's creditworthiness. "We have built our own machine learning sort of proprietary score. This helps us to underwrite which users should be given how much credit," says Taku of MobiKwik.

BNPL has also caught the imagination of India's middle class, which is growing in tandem with the gap between aspiration and affordability. "People are becoming more aspirational," says Patel of LenDenClub. But they get no support from the traditional banking system that still demands salary slips and other proof to ensure income stability. This is why credit penetration is extremely low in semi-urban and rural areas. Government statistics show the bank credit outstanding in the rural areas was 10 per cent of GDP in 2019-20, a far cry from the 67 per cent nationwide number. But the sheer potential of this section of the population overshadows any hesitancy and hiccoughs for lenders. "For a non-salaried customer, there exists much patchier data. You have to use a lot more complexity in your model to make proxies and sort of guess on income and expenditure. But it's not impossible. It's a lot of common sense," says Chapman of ZestMoney.

It's a lot easier, though, to make models for customers from smaller towns and cities, who, according to industry estimates, constitute about a third of all BNPL borrowers. India's rising per-capita GDP—close to $2,000 now from roughly $1,500 a decade ago—reflects the gradual rise in income levels. Today, the proliferation of e-commerce allows people from all parts of the country to aspire for the biggest and best of brands. And when they fire up their apps, they find a hassle-free BNPL product at the point of sale that helps them afford the biggest and best. That is the core reason for the sky-rocketing popularity of BNPL. "It is more a combination of demand and the need in the market, and also the gap in the ecosystem in terms of how many people have access to credit," sums up Mehta of Freecharge. Besides, the prevalent low-interest-rate regime also helps.

However, the very proliferation of BNPL platforms has created its own problem. These new borrowers are availing BNPL offers on platforms without disclosing how many short-term loans they have accumulated. "So, the subsequent lender doesn't know if there is a problem in the behaviour of the customer," says a financial expert at a Big Four consultancy firm. As a result, many new-to-credit borrowers have multiple credit lines that ultimately result in over-leveraging. Unsurprisingly, the delinquency rate in new-to-credit customers is higher than the average in an unsecured portfolio.

However, BNPL players defend themselves by arguing that they are testing and experimenting with first-time borrowers by giving them small loan limits. As they use and repay the older loans, the platforms gradually make these borrowers eligible for bigger loans, while weeding out the truants. And all the while, their models are learning from the accumulated data.

All this, to get more eligible borrowers and issue more loans. The huge influx of private equity capital into the sector has forced BNPL companies to aggressively build their portfolio to not only beat their rivals but also satiate their investors. That means they make it easy, way too easy, to get a loan. If you apply on four or five different platforms, you can comfortably get multiple loans totalling Rs 1 lakh without any proof of income and with minimal paperwork.

This is because BNPL players mainly rely on assessing a borrower's creditworthiness through the very narrow parameters of their e-commerce and e-payments history. "We use analytics to understand a consumer's background and get insights into their purchasing behaviour to determine their spending limit and ensure that they are not over-leveraged," says Anup Agrawal, business head of PayU-owned BNPL provider LazyPay.

So, how do they assess a customer's intent or ability to repay when there is scant data on their income and savings? By data triangulation. For instance, the platform compares a customer's residence address in the mandatory KYC (know your customer) document and the delivery address keyed into the shopping portal. If they are different, it is red-flagged as a deliberate ploy to avoid payment. There are many other such factors in their digital data armoury, claim BNPL players, to help check the 'intent' factor. "We have developed models that are accurate, predictive, and far superior to something like a credit bureau file because, by definition, on a new-to-credit customer, the credit bureau file will be very, very scant," says Chapman of ZestMoney. In fact, BNPL platforms say the past two pandemic years have helped stress-test their underwriting models.

The small ticket sizes also make it easier for companies to carry out their risk assessment, says Vijay Mani, Partner at Deloitte India. "Typically, the credit limits in BNPL are less than Rs 25,000. As a result of all these factors, it is feasible to adequately measure and manage risk, even considering that BNPL is often associated with new-to-credit customers," he says.

Typically, the credit limits in BNPL are less than Rs 25,000... it is feasible to adequately measure and manage risk [even for] new-to- credit customers

Vijay Mani

Partner

Deloitte India

However, the rising NPAs (non-performing assets) in BNPL loan books indicate that while risk management may be feasible, lenders are perhaps a little too relaxed in their approach. "The NPA estimates show that the delinquencies are in double digits in BNPL portfolios, which indicates that the BNPL players are not doing a great job of correctly assessing the creditworthiness," says the consultant. But they also explain, "BNPL is an unsecured loan after all. Historically, the NPAs are higher in the unsecured segment."

Besides, BNPL lenders start with small-ticket loans and increase the limit only based on customer behaviour, adds Sriram Ramnarayan, Country Head, India and South-East Asia Business, Creditas Solutions. "So, while BNPL loans initially see a higher delinquency rate compared to standard credit products, over the long term, they can perform equally well," he predicts.

While BNPL loans initially see a higher delinquency rate compared to standard credit products, over the long term, they can perform equally well

Sriram Ramnarayan

Country Head

India and South-East Asia Business, Creditas Solutions

But the risks in small-ticket lending are disproportionately higher. "If you look at credit bureau data, the small-ticket lending has a pretty high risk compared to a large-ticket lending business," a credit bureau official says on condition of anonymity. And won't numerous small credit transactions make it more difficult for borrowers to keep a track of their total credit lines and, therefore, to repay on time? Not quite, says Shilpa Mankar Ahluwalia, who leads the fintech practice at law firm Shardul Amarchand Mangaldas. "The size of the loan is not really correlated to the risk of default," she says.

Chapman pitches in, saying there is a positive selection bias while selecting borrowers as BNPL platforms work with merchants and within a transaction framework. "You are not targeting credit-seeking customers who are desperate for credit. Instead, you are working alongside consumer durable brands and offering finance at the point of sale so that it leads to low risk," she reasons. In fact, BNPL players say they're helping people in smaller geographies test and cultivate their creditworthiness before they graduate to the big-ticket home or auto loans. "A credit card will rip them off whereas a BNPL credit journey will help in creating a good credit culture," says a fintech executive who did not want to be identified as criticising another loan product.

Experts, however, argue that people from smaller towns and cities are too naive to understand the implications of over-leveraging. But lending is only one side of the BNPL coin; collection is the other equally important side. Banks and the larger NBFCs have mastered this over the years and have well-oiled collection machinery. But unregulated entities or over-aggressive players can use hard collections methods. There have been instances of a few Chinese BNPL firms operating like local moneylenders and deploying arm-twisting collection methods. In fact, law enforcement agencies are investigating a few of them after borrowers died by suicide in some cases.

There are also a host of other issues that catch first-time borrowers unawares. These range from improper or unclear disclosures on the interest terms to the lack of a proper customer protection framework in some regions.

All this cries out for stricter regulatory oversight, not just to protect customers but also the economy.

Clearly, BNPL, an unsecured, small-ticket loan product, is expanding in the unknown territory of new credit borrowers in smaller geographies. And if Indian BNPL players grow to the size of some of their global counterparts, there is a likely debt trap ahead for these borrowers.

India's household debt to GDP has already grown from 30 per cent in 2017-18 to 37 per cent in 2019-20, even without the BNPL mania. But that debt is still substantially lower than in other major countries—the US is at 77 per cent, whereas China is at 62 per cent. That alone shows there is an opportunity for BNPL players to help Indians accumulate debt. Indeed, it is necessary for the economy, reasons Patel of LenDenClub. "If we are aiming for a $5-trillion economy, some amount of debt will have to be taken. No country has developed without taking debt."

But the staggering growth in the unsecured BNPL market could put the entire financial system at risk down the line. Especially if platforms cut corners. There are instances of companies not doing proper KYC documentation or credit bureau checks. Sometimes they don't even report a default to the credit bureau agencies. "This kind of lax attitude could lead to over-leveraging, which in turn increases the default rate, which also has the potential to impact the entity and the entire ecosystem," says a retired banker on condition of anonymity. This is exactly what happened in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis when many foreign lenders such as Citifinancial and Fullerton had to shutter their small-ticket, unsecured loan business.

In India, these short-term loans are growing at a fast clip. At the system level, traditional banks have less than 10 per cent of their lending in unsecured assets. Conversely, this number is very substantial for business models like small finance banks (SFBs), NBFCs and fintechs. And unlike banks, these lenders don't have a diversified book to absorb any NPA shocks. Mani of Deloitte, though, argues that BNPLs pose a lesser systemic risk than other digital lending products where there is low to no visibility on spends and where the value at risk is much greater.

While some industry experts say the current economic environment isn't ideal to assess the performance of BNPL players, others say these platforms are not stress-testing their business models enough to manage worse circumstances. The traditional banks and NBFCs have gone through many cycles and understand the risk if things go bust. On the other hand, BNPL players are yet to see a full economic cycle, from boom to bust. However, it is for this very reason that one should not judge BNPL, says Ramnarayan of Creditas Solutions. "High growth and competition exist in sectors other than BNPL, but it doesn't mean that players are compromising on credit standards. Let's not hold a sector guilty before it has seen the light of the day," he says.

But that's no reason for regulators to stay on the sidelines, especially as non-bank entities such as e-commerce companies are offering BNPL options. These companies, like Amazon Pay, have prepaid payment licences and partner with lenders at the back end to facilitate the loans. Globally, too, BNPL is giving regulators a headache. Major players such as Affirm, Afterpay, Klarna, PayPal, and Zip are already on the radar of US regulators for issues ranging from regulatory arbitrage to data harvesting. The UK regulator is also exploring a regulatory framework for the BNPL industry.

Back home, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) recently came out with a working group paper on digital lending, which also includes BNPL. "The RBI working group has clearly said that BNPL can only be done by NBFCs or licensed entities as a balance sheet product," says Ahluwalia of Shardul Amarchand Mangaldas. The issue here is that the entire BNPL ecosystem of credit assessment, consumer protection, data privacy and payment recovery is outside the banking system. Moreover, there isn't much control over the disclosure practices regarding charges and interest rates at unregulated front-end companies.

There is also the possibility of BNPL firms sharing customer data without consent, or even selling data to third parties. What does one do in such cases? "An aggrieved borrower should reach out to the customer support team of the solution provider who will be able to help them with the issue," says Agrawal of LazyPay.

For now, though, borrowers aggrieved by the traditional lending system are reaching out to BNPL platforms in hordes for credit. Its ease and mere availability override their concerns, if any. Two months ago, fintech BharatPe entered the fray with an interesting marketing tagline, "De Dena Aaram se." That translates to "take your time in paying back".

Taking on debt never sounded more enticing.