Please rotate your device

We don't support landscape mode yet. Please go back to portrait mode for the best experience

The Tipping Point. Yes, we know it is a book by Malcolm Gladwell. But we don’t know if Mahendra Singh Dhoni has read it. What we do know is that this legendary wicketkeeper-batsman marshalled a relatively young and inexperienced team that ultimately led to the tipping point for Indian cricket’s burst into the modern era and dominance since. On a warm afternoon on September 24, 2007, Pakistan were within touching distance of victory in the final of the inaugural Twenty-20 (T20) World Cup in the historic South African city of Johannesburg. Star Pakistani batsman Misbah-ul-Haq had hit the second ball of the final over for a six. With just six more runs needed for victory, the batter wanted to finish off proceedings with a flourish. Misbah went for the scoop shot over short fine-leg, but only skied the ball—and was caught. Pakistan were all out and India—led by first-time captain Dhoni—were champions! The victory saw India erupt into unbridled celebration, with a frenzy not seen since the country’s first ICC tournament victory, the legendary ODI (one-day international) World Cup win at the hallowed Lord’s ground in England in 1983. Then, too, a bunch of no-hopers had gone on to lift the then greatest trophy in the sport.

The 2007 win and the subsequent hysteria birthed a new idea in the brains of Indian cricket’s administrators and money managers—T20 cricket could be milked for far more money than the sport had ever seen before. And thus, it was that on April 18, 2008, was born the Indian Premier League or IPL, with the first match between Kolkata Knight Riders and Royal Challengers Bangalore seeing the former pulverise its opponent courtesy a knock for the ages by Kiwi wicketkeeper Brendon McCullum. That explosive knock by McCullum (158 in 73 balls, 13 sixes) was emblematic of the journey that the IPL would take, not just for Indian cricket as a sport, but also for Indian cricket as a multi-billion-dollar industry. “The rest of the world was saying the IPL was much bigger than what Kerry Packer had done in the 1970s,” says celebrated cricket commentator Harsha Bhogle. “We had players prioritising the IPL over everything else since there was big money to be made.”

Its [IPL’s] capacity to aggregate viewers at such scale in a short burst of time combined with the intense engagement it delivers renders it unique

Sanjog Gupta

Head-Sports

Disney Star

Today, the IPL, spread over eight weeks, with 10 teams comprising a total of 163 players, many of who are from other countries, and played across 12 cities, is a spectacular, fast-moving caravan of sheer entertainment, sporting conflict, heroes, villains, and humongous crowds of men, women and children in the stadiums—and multiples of that at homes and screening centres across the country—screaming themselves hoarse with every six and four, and equally, screaming in agony with each dropped catch and each wicket.

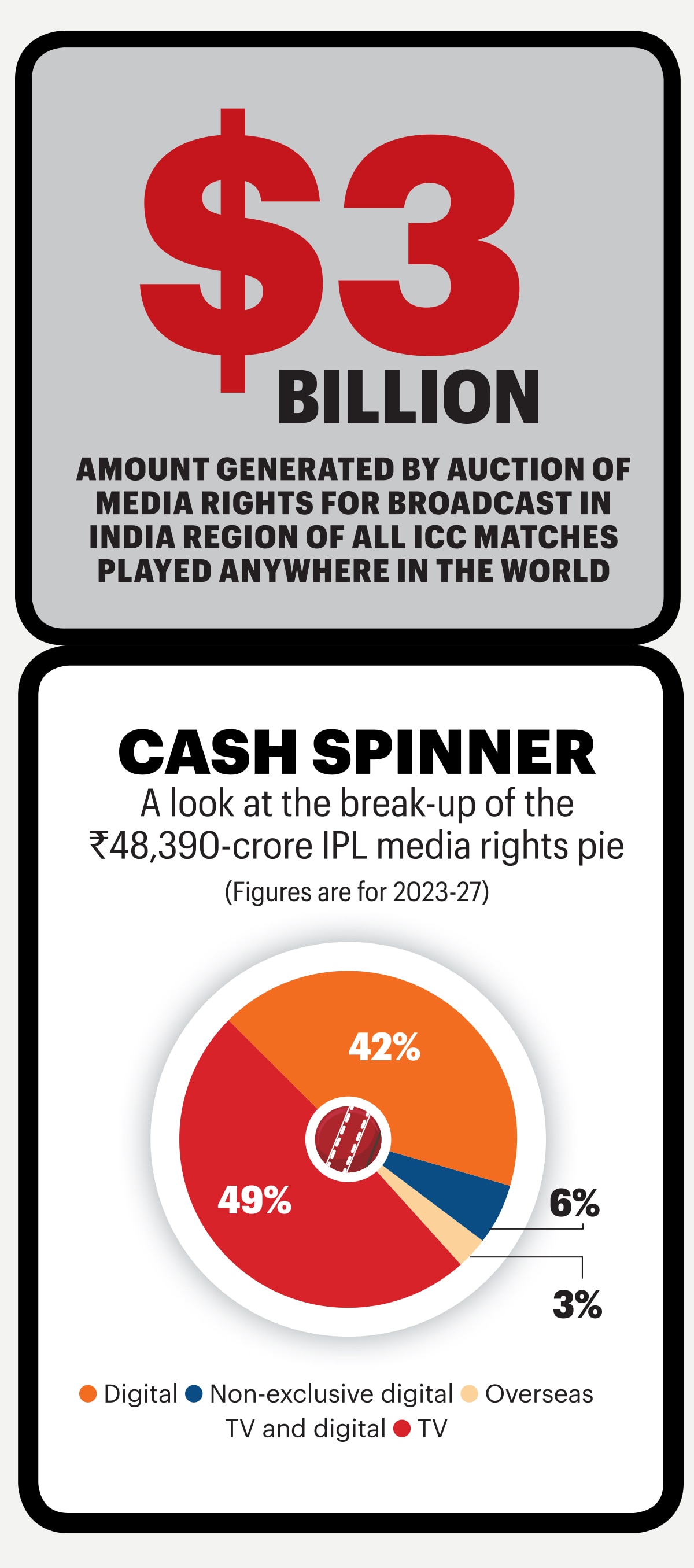

This kind of popularity and involvement of the audience, the league’s core customer, has made IPL a veritable money-spinning machine. Media rights for the tournament have been climbing. In 2008, Sony had paid Rs 8,200 crore for television rights for the period 2008-17. After that, the then Star India picked up the television and digital rights to the marquee tournament for RS 16,348 crore ($2.55 billion) for the period 2018-22. Smelling more money, the television and digital rights were then split and given to two different entities—Disney Star for television and Viacom18 for digital streaming—for a combined value of RS 48,390 crore ($6.2 billion) for the period 2023-27.

That makes IPL the fifth-most valuable sporting league in the world, an appellation that would bring a wry smile to your face, considering the top-drawer of the sport comprises just about seven to eight countries. “Purely from a financial implication, the arrival of the IPL is the biggest tipping point since it moved the balance away from two to three established powers towards India,” says Bhogle.

IPL is now behind only four major leagues—the National Football League in the US (NFL, media rights worth $112.6 billion for 2023-33); the NBA (National Basketball Association, $24 billion for 2014-2025); English Premier League soccer ($12.85 billion for 2022-25); and Major League Baseball in the US ($12.24 billion for 2022-28).

But Indian cricket is not only IPL. Media rights for International Cricket Council (ICC) tournaments have also been sold for close to $3 billion to Disney Star. The impending sale of rights for all bilateral matches to be played in India and organised by the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) is expected to fetch at least $1 billion. And if you add what IPL’s two new team owners spent last year, that’s almost RS 13,000 crore. Adding to these what other IPL team owners have paid in the past, cricket in India is a RS 1 lakh-crore industry. That’s big, and it’s only growing bigger.

A Win-win Situation

According to Sanjog Gupta, Head-Sports at Disney Star, nothing unites audiences across the country like cricket. The fact that the IPL is watched by an audience of more than 600 million between television and digital bears testimony to that. “Its capacity to aggregate viewers at such scale in a short burst of time combined with the intense engagement it delivers renders it unique. The expanse of that aggregation is unlike anything else, including cinema,” he says.

Cricket serves both tactical and commercial objectives due to short bursts of aggregation and engagement as well as strategic intent, given its ability to recruit audiences and facilitate the building of a portfolio, platform or business on top of it. “One can build a robust business model around a core proposition that cricket helps build,” says Gupta.

Lloyd Mathias, business strategist and former marketing head of PepsiCo India, Motorola and HP Asia-Pacific, believes IPL has managed the unique feat of being a win-win for all seven parties—players, audiences, team owners, businesses, media companies, BCCI and Indian cricket. “Players who bagged a single-season contract were suddenly making more money than they did after playing 10 years of domestic cricket. Of course, one great season for the player [also] means attention from the national selectors,” says Mathias. For audiences, the IPL was a chance to see world-class cricketers competing fiercely with their favourite local stars in a glamourised version of the sport. “Team owners got financial benefits that were not initially apparent. Today, each of the original franchises has easily made a 25x return [in terms of valuation] on its original investment, with other benefits and bragging rights,” he adds.

There is no plan to charge a subscription fee for sports... We have done well on digital advertising during this IPL and believe there is still a very large opportunity

Anil Jayaraj

CEO

Viacom18 Sports

As for the BCCI, 50 per cent of the revenues from the sale of IPL media rights go into its coffers, with the rest going to the teams, while Indian cricket is rewarded with talent that otherwise might not have been spotted. Businesses—advertisers, sponsors, and their ilk—have also found their association with the sport beneficial, while for media companies, cricket gets them the eyeballs (more on that later).

At this year’s IPL, JioCinema, Viacom18’s OTT platform, disrupted the status quo by streaming the tournament free of cost. “We provided unrestricted access to anyone who wanted to watch it in a frictionless manner without a paywall or subscription,” says Anil Jayaraj, CEO at Viacom18 Sports. One more component of the strategy, says Jayaraj, was for the audience to watch it in cohorts, which led to 17 simultaneous feeds across 12 languages including English, Hindi, Marathi, Bengali, Tamil, Bhojpuri and Odia. “Long-form content on digital is a reality today, and with 700 million internet users in India, a lot can be done.”

The Smell of Money

Streaming the IPL free on JioCinema means advertising will be the only source of revenue for the company. But some say that advertising during cricket tournaments is an expensive proposition. For instance, in 2017, a 10-second IPL spot went for RS 6.5 lakh; now it is as high as RS 17-18 lakh. Are they worth the expense? Mathias says the tournament provides a highly engaged audience due to the high-intensity games. “The visibility on television can cause a surge in immediate interest as well as brand recall at a later stage. Besides, cricket, as a sport, is immensely advertiser-friendly, with spots after every over, every wicket and numerous breaks.” But for advertisers, can cricket deliver? “To say nothing can deliver as much as cricket is not correct. The question is, how much the advertiser needs to spend to get to that reach,” says Mayank Shah, Senior Category Head at Parle Products. He admits that cricket does bring a larger audience than the largest general entertainment channels, but “one must understand the rates that come with it are also very high”.

Shah’s company is one of the associate sponsors that Disney Star signed on for this year’s IPL. In a year when some of the high-profile start-ups/unicorns (like BYJU’S and Livspace) were conspicuous by their absence, he got an “attractive rate”, says Shah, without getting into details. In 2022, when Disney Star had both the TV and digital rights, it is said to have raked in RS 3,500 crore by way of advertising revenue—RS 2,900 crore through television and RS 600 crore on Disney+ Hotstar, its OTT platform. For 2023-27, more than RS 9,000 crore will need to be made each year by those holding the media rights—just to recoup their investment. Those like Shah are not willing to commit right away for the ICC Men’s Cricket World Cup 2023 (ODI) to be held in India. “Benchmarks will obviously change and we need to take a close look at how much money we are left with,” he says. From a broadcaster’s point of view, the IPL also serves as an audience funnel for other cricket properties and even other sports. Disney Star’s Gupta outlines how the network leveraged the IPL to promote the ICC World Test Championship (WTC) as well as entertainment properties including movie and show launches. “A robust cricket portfolio allows us to stay connected to the cricket fan and keep him on a journey with the network. During the WTC final, we will promote upcoming properties like the Asia Cup and the World Cup. On Asia Cup, [we will promote] the World Cup and then on the World Cup, India’s tour of South Africa and Pro Kabaddi. Building a round-the-year portfolio of cricket helps direct audiences, builds stronger connections with fans and creates non-linear growth in value.”

Getting back to how effective cricket is for businesses, let’s look at water purifier maker Kent RO Systems, one of the principal sponsors of the Sunrisers Hyderabad team. The company, at one point, was the title sponsor of Kings XI Punjab (now called Punjab Kings). “IPL offers mass reach and where else will you get TVRs (television viewer ratings or the percentage of the population watching a show) of 4-5?” asks Mahesh Gupta, the company’s Chairman & MD. As for IPL ad spots being expensive, he says that his company’s logo is visible for one and a half hours or half the duration of the game. “The tournament runs for two months and every match is interesting, compared to the World Cup where viewership is only for the India matches. The IPL is expensive but gives the advertiser an assured audience.” Of his overall advertising and promotion spend, the IPL accounts for a handy 20 per cent.

IPL was already a big property with access to widespread demographics and geographies. All our brands associated with it—Nexon, Harrier, Altroz and Punch—were successful

Vivek Srivatsa

Head of Marketing, Sales and Service Strategy

Passenger Electric Mobility

Kent isn’t the only company to have tasted success. In 2018, salt-to-software conglomerate Tata group got involved with the tournament as an associate sponsor through Tata Motors. “IPL was already a big property with access to widespread demographics and geographies. All our brands associated with it—Nexon, Harrier, Altroz and Punch—were successful,” says Vivek Srivatsa, Head of Marketing, Sales and Service Strategy at Tata Passenger Electric Mobility. Now, as title sponsor, the group has chosen to promote Tata Neu and Tata Motors. “This is the first time we are using it for an electric version (the Tiago EV),” he says. Launched last September, the Tiago EV performed impressively in terms of bookings, but seemed to have much more potential. This was based on data that indicated that a quarter of the bookings were coming from first-time buyers, with an equal proportion coming from women. Srivatsa says the time had come to give it a big push.

This season of the IPL saw a high-decibel campaign and the results have been heartening—a 3.5x increase in the number of visits to the company’s website, while bookings are up 70 per cent since the tournament kicked off. “IPL gives you the reach. One can build a lot of awareness and it is possible to really build on that momentum,” he says.

Media rights and more

Jayaraj of Viacom18 Sports, meanwhile, says that “there is no plan to charge a subscription fee for sports” on JioCinema. That straightaway puts the onus of generating revenue on advertising. “We have done well on digital advertising during this season of the IPL and believe there is still a very large opportunity. To us, the democratisation of advertisers is a big emerging trend.”

Outlining the landscape today, R.C. Venkateish, Promoter of Lex Sportel Vision and former MD of ESPN Star Sports, says Star could not afford to miss the digital rights for the ICC tournaments after losing those for the IPL and, therefore, went the whole hog—its winning bid of around $3 billion was on a base price of $1.44 billion; a few days later, it licensed the television rights to Zee for a reported $1.5 billion. From a strategic point of view, Viacom18, owned by Mukesh Ambani-led Reliance Industries, is looking to build a digital business across its B2C platforms and the IPL fits in well since it brings in value and a loyal viewership base. That means not looking at IPL from just the perspective of advertising revenue. For Disney, a listed entity in the US, its valuation on Wall Street is today significantly determined by its OTT business—Disney Plus and Disney+ Hotstar. India is a key market and Disney+ Hotstar, which had the IPL digital rights till last year, is estimated to have got at least 70 per cent of its revenues from cricket. Protecting its subscriber base is, therefore, an imperative for Disney Star.

Rajesh Kaul, Head of Sports at Sony Pictures Networks India, says subscriptions have driven sports in larger markets, whereas in India it is a combination of that and advertising. India, he says, has over 300 million households with television penetration close to 70 per cent. “As this number increases in rural areas, it will bring newer viewers into cricket. Plus, sports gets around 40 per cent of viewership from women and that, too, can take off with how our teams are doing across formats.”

Then there are those who own IPL teams. They have invested huge sums to buy and promote them. Their revenue comes from a combination of the central pool of media rights, stadium collections and sponsorship, to name a few key sources. Rajesh V. Menon, VP & Head of Royal Challengers Bangalore, says that though the IPL is a two-month tournament, his company works through the year. “We want to build a lifestyle proposition and are not restricted to a particular region. The RCB brand has now extended into a deal with Puma for athleisure, apart from a presence in segments like ready-to-drink beverages, bar snacks and edtech,” he says. Its other forays include fitness, the Women’s Premier League and gaming.

Purely from a financial implication, the arrival of the IPL is the biggest tipping point since it moved the balance away from two to three established powers towards India

Harsha Bhogle

Cricket Commentator

If RCB has been around since the first season in 2008, last year’s winner and first-time entrant, Gujarat Titans, too is looking at the IPL with a long-term lens. “A season-to-season approach is not the way to do it. We have our plans in place for the next three to five years,” says the team’s COO, Arvinder Singh. Winning in the year it debuted has helped the cause. “It has helped us leapfrog but we still need to be relevant through the year. There is a lot of headroom for growth and our goal is to be the most entertaining franchise.”

In many ways, the maturity of a tournament is reflected in the changing nature of its ownership, more specifically, the ownership of its teams. “In the initial phase, we had celebrities and over time, the likes of a CVC (a Europe-based private equity firm) have come in as the owner of Gujarat Titans. The glamour quotient has faded away, making way for a more professional structure,” says Ajimon Francis, MD of Brand Finance India, an international brand valuation firm. He adds that the IPL has shown the way for the volleyball and kabaddi leagues. “Even on a large base, cricket in India is still at a transition point. We are seeing the US, the Netherlands, Japan and China nurturing cricket teams and this is fuelled by Indian cricket. Inevitably, IPL teams will also get listed,” he says. Brand Finance’s valuation of the IPL in 2022 was $8.4 billion.

The Way Ahead

A huge reason for the recent surge in interest in cricket has been more women watching the game. When the IPL was conceived, says Balu Nayar, former MD of sports management agency IMG India and a key architect of the tournament, the objective “was to attract large audiences, perhaps comparable to our bilateral series, and the wish was to get in a higher proportion of women than what normal cricket matches attract”. While both were achieved, there has also been a reasonably good growth on a high base.

The T20 format has been around in nations like Pakistan and Bangladesh for a while but with negligible impact since they are largely domestic tourneys. “We have also seen the creation of new leagues in South Africa and the UAE. The primary variable for the success of any sporting league lies in both the quality and quantity of its audience, which in turn defines the value of the media rights. These two leagues will not reach the heights of the IPL without garnering a substantial share of the Indian cricket audience,” says Nayar.

Bhogle is blunt when he says this year’s cricket World Cup will be the ultimate test for the 50-over format. “Till now, it [the World Cup] has been the pinnacle in one-day cricket and of the 48 games to be played, nine will involve India,” he says. But that shouldn’t be a problem as Indians love cricket, right? “That India is a cricket-loving country is a bit of a myth. We are an Indian cricket-loving country,” says Bhogle. He goes as far as to say that if the IPL continues to grow at this frenetic pace, the cricket World Cup will lose some of its importance. “There is a good chance that the IPL will get larger than it.”

According to Venkateish of Lex, the global pecking order across sports indicates a diminishing value for bilateral tournaments and what works is a single, multi-nation format. A prominent example is any inter-nation football tournament versus the FIFA World Cup. “The [cricket] World Cup will have value, but how much traction a bilateral series can generate is a question mark. India playing nations such as West Indies, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and New Zealand have dropped off the radar,” he says. That only leaves India playing Australia, England and South Africa, with Pakistan looking unlikely in the current scenario. “But ICC will need to push it since smaller countries need the bilateral series for their own survival. Let’s not forget that the IPL and World Cup together account for 80 per cent of the pie on both revenue and viewership.”

The question on everyone’s mind is how long the cricket express can maintain this speed. “Every year that keeps getting asked and then you see people consuming the IPL differently... I think the juice left will really depend on how keen those in the 15-25 age group are about cricket,” says Bhogle. For a nation with over a billion people and cricket being the largest unifier, even the most conservative will agree that a lot more can be done. Be it on viewership, innovative formats, smart marketing, new venues or different ways of watching the game, cricket is here to stay. For a long time.

Story: Krishna Gopalan

Producer: Arnav Das Sharma

Creative Producers: Anirban Ghosh, Raj Verma

Videos: Mohsin Shaikh

UI Developer: Pankaj Negi