The only flaw with success is that it is often short-lived. In 2005, when Carlson Rezidor Hotel Group launched its upper-midscale brand Park Plaza in Gurgaon, Delhi's satellite city had just three branded hotels - the Trident, the Bristol and 32nd Milestone. Supply of hotel rooms was minuscule compared to the demand in a city that was fast emerging as an IT outsourcing hub and the preferred headquarters for MNCs in India.

For the foreign chains looking for easy pickings in a supply-starved nation, India has proved to be an unexpectedly complex market to crack. The initial easy years lulled them into complacency and led them into making serious mistakes. A bloodbath ensued between 2008 and 2014, testing their endurance and resources. Some have emerged wiser and stronger. Some are still licking their wounds. So which are the chains that have deciphered this cruel market, spotted the opportunities and cracked it open, and which have lost the plot?

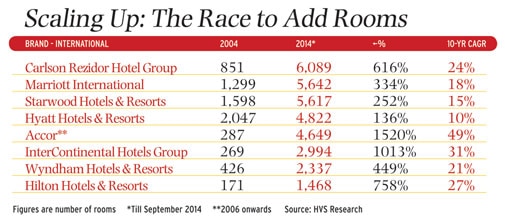

Besides Carlson, chains such as Marriott International, Hyatt and Starwood seem to have done well due to their ability to tie up with a stable group of developers, their strong distribution network and consistency in delivery of services across a bouquet of brands. French group Accor has got its act right in the mid-market segment, and tried to create a niche for itself in the convention business but struggles with its upscale brands. Others such as Hilton and InterContinental Hotels Group (IHG) are facing issues with developer-partners, and getting the right brands in the country.

The Scale Trap

The first foreign chain to put its flag in India was perhaps IHG, which tied up with the Oberoi group some 49 years ago to create a five-star hotel in Delhi. A few others arrived sporadically, but the real invasion of the foreign chains began in the late 1990s and early 2000s, with the coming of the world's biggest hotel operators - Marriott, Starwood, Hyatt, Accor and Hilton. They came in, set up development teams to scout for partners to build a base and began an aggressive onslaught. "It was a mad rush between 2005 and 2007. Stock markets were booming, disposable incomes were rising, and inbound and outbound travelling was growing tremendously," says Achin Khanna, Managing Director (Consulting & Valuation) at hospitality consultancy HVS South Asia. "The economic slowdown spoiled the party."

Daniel Welk, Vice President (Operations - India), Hilton Worldwide, blames the slowdown in the real estate sector for the failures. He says Hilton still operates DLF's asset in Delhi's Saket. "During the global downturn, DLF divested its non-core businesses and withdrew from hospitality. It was not a bad decision. The JV was the victim of circumstances post the financial meltdown," says Welk.

The Right Partner

Many feel that rather than chasing scale, managing relations with property owners is most crucial in India. "Till a few years ago, every developer with a piece of land wanted to build a luxury hotel. Nobody wanted to build a mid-market or budget hotel. Now people understand that investment-return equation for a luxury hotel is completely different from other segments," says a consultant.

Dealing with a diversified set of owners and still managing to keep complete control of the properties is an art which only a few operators have learnt. Unlike the US, where most hotels are owned by financial institutions which only look at returns on investment, in India there are broadly three different kinds of owners: the local big businessman who has a lot of spare cash, institutional owners and big real estate developers. Almost all of them are loath to relinquish control and tend to interfere a lot in day-to-day running. "These are very different people. There's no one-size fits all approach to deal with them," says Dilip Puri, Managing Director (India) and Regional Vice President (South Asia), Starwood Hotels & Resorts.

Choosing the right partner and contract terms is a tricky proposition. "We tell developers upfront that Marriott is a difficult operator to deal with. Our agreements are inflexible. My pitch to owners is when you build a hotel, it is like building an airplane. It costs you millions of dollars. Are you going to negotiate and find the cheapest pilot or do you find somebody who has experience," says Marriott's Ahluwalia. "We want a bunch of 20 to 30 owners with us. That's why just 10 to 15 per cent of the proposals convert into contracts," he says.

Unlike other chains, Hilton has a series of failed marriages. It had issues with the Oberoi Group over the branding strategy and with the Delhi-based Eros Group - where it was managing three hotels - over poor performance of the hotels. Hilton has just 14 hotels, way short of Carlson's 73 properties. According to Virendra Bhatia, Managing Director, Baani Group, who owns Hilton Garden Inn in Gurgaon -launched in February 2013 - the first year was challenging as the Hilton management was not stable. "In the past year, they have got their feet on the ground and things are improving," he says. Yet, for his next two hotels coming up in Manesar and Gurgaon, he is keeping options open on which chain to tie-up with.

One problem that could have plagued Hilton is the lack of local insight. Starwood's Puri says the ability to understand the need for local leadership and expertise is rare. "Almost all my counterparts in competing international chains are expatriates who come for just one-two years," he says. In Hilton, for instance, Welk joined in December 2013 after Guy Hutchinson, its previous India head, had spent only about a year.

What Hilton's experience shows is that even after a contract is signed, things can go wrong as managing relationship with owners is a constant challenge. Brands like Carlson, Starwood, Hyatt and Marriott have shown some stickiness with a group of developers. Carlson has a relationship with seven developers with whom it has done multiple hotels. With Gurgaon-based Bestech Group, it operates three hotels (two Radissons and a Park Plaza) while 49 hotels (Park Inn) are in the pipeline.

Over the past 10 years, developers like Rahejas in Mumbai, Salgaocars in Goa, Chordia (of Panchshil Realty) in Pune, and Prestige Group in Bangalore have set up multiple properties with different international operators. "It helps in bringing down the costs because of the synergy. Developers can have common staff for functions like marketing and distribution," says Atul Chordia, Chairman of Panchshil Realty, which runs three Marriott hotels and a Hilton franchisee.

"Mature owners understand the hotel industry dynamics, so it is easy to work with them," says Harleen Mehta, Vice President (Sales Operations - South Asia) at Hyatt Hotels.

But that stickiness is increasingly difficult as developers get savvy about the right brand for their property. Take Bangalore-based developer Brigade Hospitality, which has done deals with Starwood (Sheraton Brigade Gateway), Accor (the Grand Mercure in Bangalore and an upcoming one in Mysore), and IHG (for a Holiday Inn scheduled to open this year in Chennai). Nirupa Shankar, Director, Brigade Hospitality, describes the logic behind choosing different partners - for an IT hub like Bangalore, it made sense to go with a US chain with a strong loyalty programme (Starwood), while to tap the leisure market a European chain like Accor would resonate with the Mysore-bound tourists arriving predominantly from France.

Industry experts feel the tenure of the contract makes a difference in a hotel's performance. Long-tenure hotels are good for both promoters and hotel chains because most hotels make money in the long run. Typically, the average break-even period for hotels in India is seven to 10 years. Supply glut, low demand and high inflation have pushed the break-even period by one-two years in recent times.

"Some hotels do well with age. We sign 25- to 30-year contracts. We are lucky to have mature owners who don't make unjust demands," says Hyatt's Mehta. Marriott too signs 30-year contracts. IHG and Hilton have 15 to 20-year contracts.

What surprises many is the way the foreign chains have made such deep inroads into a country where hospitality is perceived to be in the local gene. How have they overtaken the Oberois and Leelas and frightened the Taj and ITC into taking rearguard action? Why have developers preferred to do business with them rather than the local chains? Domestic chains have adopted the management model only recently while foreign chains took the route from the start.

Brigade's Shankar says: "It's not that we are averse to Indian players but from business point it makes sense to tie up with an international chain as they are very good with training and SOPs and employees get career growth." The global distribution system of the foreign chains is also the reason why Brigade tied up with global chains. "A third of our business is the Indian traveller but a lot of it comes from the US and Europe," she says.

The Distribution Edge

Foreign chains hard sell their distribution strength to local owners. And that has worked. Distribution is about presence at locations where guests want a brand to be. It includes having product offering at different price points - luxury, upscale, mid-market and budget. In India, hotel demand is primarily driven by corporates and conferences - around 60 per cent. Corporate executives travel around the world, so distribution for foreign chains includes their global footprint.

A hotel with better distribution is always at an advantage when it comes to corporate clients. It can capture demand from companies at different levels. "As a corporate traveller, you want to stay and have a relationship with a hotel chain because you collect reward points and you can redeem those points and take your family for free stays," says Ahluwalia, adding that Marriott has covered all metros, and is trickling down to smaller towns such as Ahmedabad, Guwahati, Bhopal, Indore, Nagpur, Agra and Siliguri.

Of course, not all foreign chains are equal in this respect. Hilton seems to be lagging behind in the distribution race. Its operating hotels are in metros and even its 17-hotel pipeline is skewed towards mostly metros - Delhi, Pune, Kolkata, Hyderabad, Chennai and Mumbai.

Industry observers say Carlson has done a good job in expanding its distribution network while keeping its partners satisfied. It is the largest chain at the moment in terms of hotels and has a strong pipeline. "They have a good market share," says Manav Thadani, Chairman, HVS Asia Pacific. Kachru says their hotels are present in 75 per cent of state capitals and the plan is to cover each one of them. Carlson has a mix of managed and franchisee hotels in India which many say have affected service standards and consistency in brand.

Under the franchisee model, the property owner runs the hotel and the hospitality chain lends its brand name, technical and pre-opening support, reservation system, and its loyalty programme. "In terms of being a pure management company, the only way we can differentiate us is when we deliver better results than our competitors. Whichever segments we want to operate in, we want to be the best in class," says Rajeev Menon, Area Vice President (South Asia) at Marriott International.

Some hotel chains think otherwise. The US-based Wyndham Hotels Group follows the franchisee model, which it says is developer-friendly model. Deepika Arora, Regional Vice President (Indian Ocean), Wyndham Hotel Group, says the chain prefers this model as it allows owners more flexibility. "I was able to sell this model because we were offering everything that others were offering but at a much cheaper rate. We are not very uptight when it comes to product, fees or investments. I tell developers to meet my minimum specifications, and they can keep control of the property," she says. Wyndham has grown from five to 23 hotels in five years.

Going forward, the distribution advantage might not work for the foreign chains as the big play moves to the economy- and mid-market segment. Here, since the target traveller is Indian, it's local distribution that counts rather than global. A chain like Lemon Tree is looking to capitalise on just that.

The Right Brand Matters

As the market is maturing, a clear distinction between different chains is visible. Starwood, Marriott, Hyatt have established themselves as premium brands whereas Accor, Carlson and IHG are seen as mid-market chains. A bit ironic, considering that IHG played a part in creating India's first modern five-star hotel. But at the moment, it has mostly focused on economy and mid-market brands like Holiday Inn Express, Holiday Inn and Crowne Plaza. "Their development team is not keen to push the iconic InterContinental brand," says Khanna. "IHG has powerful brands like Holiday Inn but has never stayed here for the long haul. It has a long way to go," says another consultant.

Starwood entered India in 1973 when it tied up with the Oberoi Group to launch the Oberoi Sheraton in Mumbai. In 1979, ITC tied up with Starwood to use the Sheraton brand for three properties but in 2007 Starwood decided to operate the brand on its own. In return, Starwood gave its Luxury Collection brand to ITC. Under the agreement, ITC runs 11 hotels, including iconic properties like ITC Grand Chola in Chennai, ITC Maurya in Delhi, ITC Maratha in Mumbai, and ITC Sonar in Kolkata. Starwood claims it is profitable in India, as do Marriott and Carlson.

The Road Ahead

It needs deep pockets, staying power and a lot of cultural adaptability to survive in India. That's a tough lesson that all the big global hospitality chains have learnt so far. Going forward, the global chains are going to face a fresh set of challenges as the big three of Indian hospitality - Taj, ITC and Oberoi - are now changing their models to defend their turf.