Almost all billboards in the two-lane industrial corridor of Chakan, Pune, advertise ambitious real estate projects. All thanks to the suburban town’s growth as an auto manufacturing hub after hosting global automotive giants like Mercedes-Benz, Volkswagen (VW), Bridgestone, Bosch, etc., earning Chakan the tag ‘Detroit of India’. Battered by the pandemic, the automotive micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) of Chakan and adjacent areas like Talegaon and Pimpri-Chinchwad are pinning their hopes of revival on pent-up demand, growing exports and the electric vehicle (EV) disruption.

Today, there are about 40,000 to 50,000 small and large companies in the area. More companies continue to make investments here, especially since the demand for electronics and software-enabled components is rising. In June 2019, Harman—a fully-owned subsidiary of Samsung Electronics—invested Rs 350 crore in its existing Chakan plant to expand capacity 12-fold by 2022. The company said that in the next three years, the production of digital cockpit units (DCUs) and telematics control units (TCUs) from its Chakan plant would increase from 200,000 units to over 2.5 million units annually. This would allow them to manufacture customised connected car electronics solutions for large domestic and global customers including Maruti Suzuki, Mercedes-Benz, the VW Group, Tata Motors and Fiat Chrysler.

Chakan is spreading its wings when it comes to research and development (R&D), too. The central government’s Automotive Research Association of India has an institute in Pune that provides advanced research, development, testing and certification services in the field of automotive R&D. Lumax Cornaglia Auto Technologies, a 50-50 joint venture between Lumax Auto Technologies and the Cornaglia Group of Italy, set up a new R&D centre in Chakan and is working on air intake systems, urea tanks, other automotive tanks, CAC ducts and other blow-moulded parts. The centre is aimed at enhancing the local design, development and testing capabilities to provide localised solutions to OEMs. “Across sectors, Tata and Mahindra are No. 1 and No. 2 in R&D spending in India. Clearly, those benefits will trickle down to MSMEs. That augurs well for the economy but we have to make sure that we stay abreast with new technologies,” says Jiten Divgi, Managing Director of automotive powertrain solutions maker Divgi TorqTransfer Systems.

Another advantage is the adequate availability of unskilled, skilled and managerial workforce, and learning opportunities for employees in the many institutes of higher learning in the vicinity.

It all began after Tata Motors and Bajaj Auto set up their first plants in the 1960s. Tata Motors’ facility was set up in 1966 in the Pimpri-Chinchwad area, and today it can produce over half a million vehicles for both domestic and international markets. Sandvik Asia, Atlas Copco, Alfa Laval and SKF Bearings followed suit and were key to growing the area’s industrial activity. But it was the arrival of international OEMs like Mercedes-Benz, Piaggio, Skoda, General Motors (GM), VW and Fiat that put it on the global map as an auto hub. “When OEMs come, ancillaries also come rushing in. These German and Korean foreign players came as fierce competition. Our local companies had to up their game. That hastened the development and upgrade of the whole ecosystem,” says Vinnie Mehta, Director General of the Automotive Component Manufacturers Association (ACMA).

Today, the Chakan auto cluster has around 750 automobile manufacturing units that employ close to 250,000 people. Local businessmen say the Maharashtra government has played a key role in attracting investments and developing this area into a full-fledged industry.

At a recent conclave, Aaditya Thackeray, Minister for Environment and Tourism in the Government of Maharashtra, said that areas in Talegaon and Chakan are expected to emerge as major centres for production of EVs due to the ready automotive ecosystem in these areas. “Almost 73 per cent vendors of a global EV giant are from the state. Maharashtra has made a giant leap in terms of EV adoption,” he had said. The Maharashtra government facilitates adoption of EVs through price drop incentives and subsidies for both consumers and manufacturers under its Electric Vehicle Policy, 2021-2025, which has an outlay of Rs 930 crore.

The second largest city of Maharashtra is well on its way to becoming the EV hub of India since many start-ups based in the city crossed the landmark of Rs 1,000 crore in investments as of the first week of April. Most of these investments have been made by big players in the automobile industry such as Mahindra and Mahindra, Piaggio and Bajaj. “EV is a major disruption that the automotive industry is seeing after many years. It is a huge opportunity for us as we can leverage our existing strong relationships with OEMs to supply conventional products as well as offer the entire value chain within the EV space to our customers,” says Supriya Badve, Executive Director of Badve Engineering, a maker of two-wheeler suspension and mirrors, polymer processing, security hardware, etc., for clients that include Royal Enfield, TVS, Bajaj and Jaguar Land Rover, among others.

That said, many MSMEs depend on conventional engine parts for a living. “If fuel gets over, our business gets over. I don’t foresee that for the next 10 years when 20 per cent of auto volume will be into EVs. Going forward, engine production will move to low-cost countries. India will produce more ICE engines. Global players like Cummins are not putting [up] their own plants. They’re looking at one big engine manufacturer who will become the largest player till the time the run goes,” says Nishant Sagar, Director of Dyna-K Automotive Stampings, which caters to precision stamping and pressed components’ requirements for Tier I and OEM customers like Maruti Suzuki, Bosch, Ashok Leyland, Eicher, etc.

Mehta of ACMA says that with the industry undergoing significant transformation on the technology front, the challenge for parts makers is where to invest. “Currently the volumes in EVs are low, that’s why companies are not jumping onto the bandwagon. The government should take a technology-agnostic approach. Ultimately the customer will decide what sticks. Global companies are increasingly going for partnerships with domestic companies. Collaboration and co-creation is the way forward,” he says.

Auto ancillary makers say recovery has been quick for them post the pandemic. Divgi TorqTransfer Systems has domestic clients like Tata, Mahindra, Force Motors, Ashok Leyland, etc. “The recovery has been quite good compared to what I see in Europe and the US because we have suppliers and customers there as well. The chip shortage has affected the ability of the industry to bounce back to the full extent of its potential of recovery,” says Divgi.

Supriya Badve of Badve Engineering says her company has been able to recover much faster than competitors: “Our CAGR post-pandemic has been much higher compared to our competitors in the Tier I automotive supplier community. The volume drop in the two-wheeler industry has impacted our turnover. However, we have mitigated that impact to a large extent due to our customer-segment diversification and forays into new markets.”

Many players are looking at exports and investing in other businesses to de-risk their domestic businesses. “Our exports were at about 40 per cent last year. At a company level, we have doubled in the past two years. Our dependence on automotive is 100 per cent, which we need to bring down. De-risking is key. By the end of 2024-25, we are aiming to have at least 10 per cent business that is non-auto. We need to find products that align with our product line,” says Sagar of Dyna-K Automotive Stampings.

According to Avalon Consulting, recovery has been mixed for the auto MSME sector. “Till April-August 2020 there was a lot of distress and some companies survived. Companies that were heavily leveraged had a big problem,” says Subhabrata Sengupta, Executive Director of Avalon Consulting. When the recovery started in July-August, companies struggled to get workers back from their villages. “Now, because of the volumes, some companies may be operating with fewer people than earlier. The sector will have to be the engine of employment generation. Fundamentally, the growth slowdown can be only corrected by increasing demand, not by supply side initiatives,” says Sengupta.

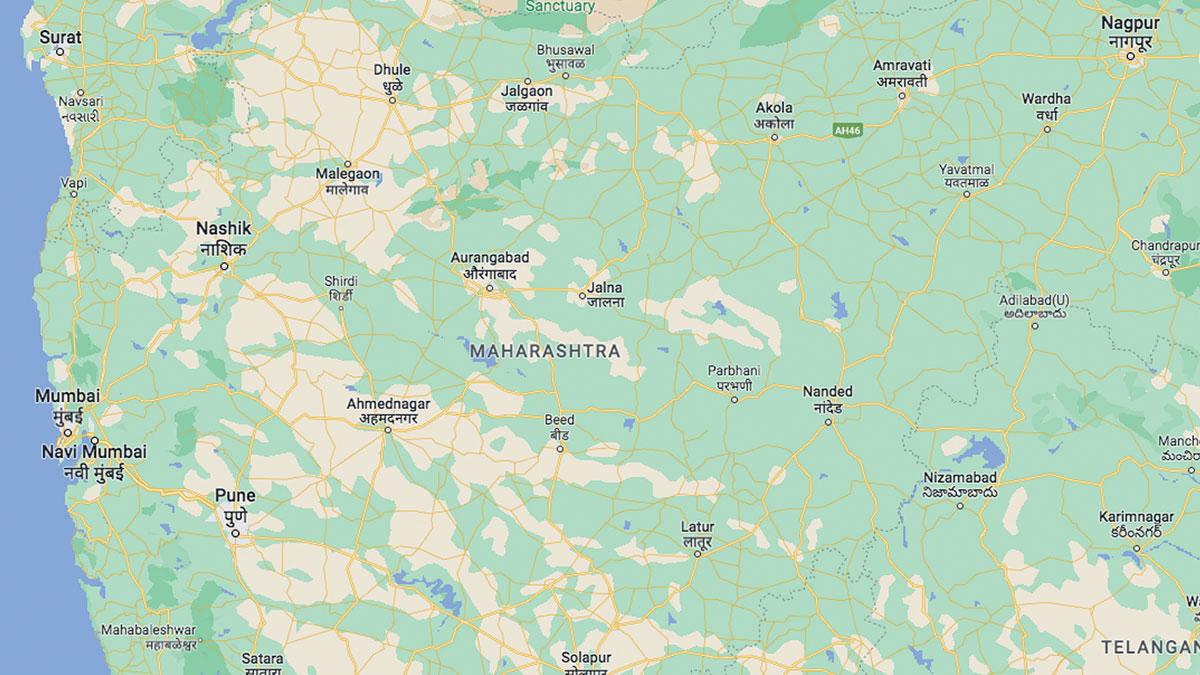

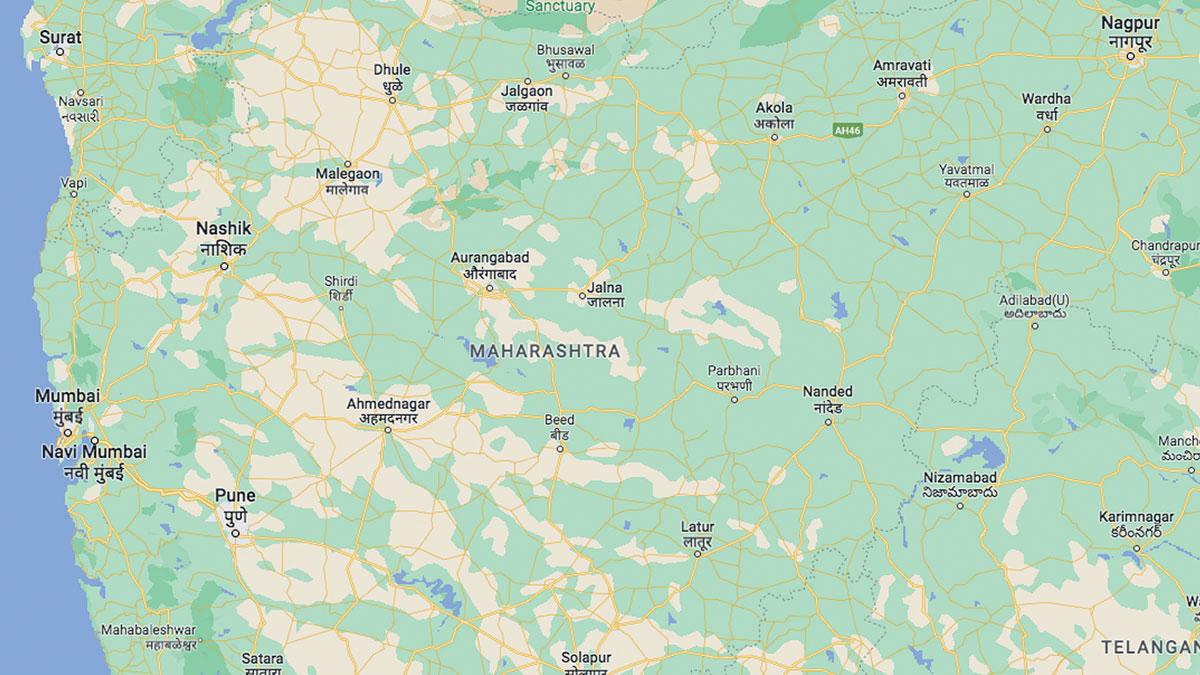

While Chakan has geographical advantages such as proximity to Mumbai and accessibility to ports, MSME businessmen from Chakan, Talegaon, Ranjangaon, and adjoining areas have long demanded that the planned international airport in Pune should be in Chakan. This will not only help them in exports but also make it more accessible. Apparently, many big companies invested in this area on the assumption that Chakan will have an international airport, but now there are reports of it being shifted to Purandar.

“We feel cheated. MNCs that invested here 10-15 years ago were told that there will be an international airport for global leaders to come, and cargo facilities taken care of, but that has not happened. It’s very inefficient for them to sustain like this at an auto manufacturing hub contributing lakhs of crores of revenues,” says Dilip Batwal, Secretary of Federation of Chakan Industries.

There are other challenges as well. Badve says local political interference hampers smooth operations, and “labour availability and repeatability during peak volumes has been a persistent issue for all industries in this belt. Infrastructure revamp (quick mode of transportation like metro or monorail) is now the need of the hour considering the large scale of industrialisation and the associated footfall”.

Batwal welcomes the Centre’s Rs 76,000-crore scheme to boost semiconductor manufacturing in India. The Ministry of Heavy Industries had also announced that a total of 115 automobile and automobile-related ancillary companies filed for the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) Scheme. But the bummer has been that “the bar to qualify for the scheme has been set too high; SMEs do not come up to that standard and size. So, it has been disappointing”, says Divgi.

The way forward for MSMEs is to not only depend on government schemes and incentives, the companies feel, but also to adapt to the fast technological developments happening in the automotive sector. And Pune’s auto MSMEs are possibly best placed to take these challenges head-on.

@PLidhoo