Finance Minister P. Chidambaram can be a puzzle at times. His penchant for being different revealed itself once again soon after he presented his eighth

Budget on February 28. Instead of granting exclusive post-Budget interviews to handpicked journalists, the way his predecessor Pranab Mukherjee used to, Chidambaram held a press conference to clarify his budgetary proposals, at which he had all his senior finance ministry officials also present. Soon enough, that vital question which spooked the stock market just after the Budget presentation, came up. It was about a change in the tax law underpinning India's international tax treaties, mentioned in the Budget papers. The question implicitly referred to Mauritius - the main springboard of foreign capital flows into India.

Chidambaram chose to give a short tutorial on the subject. A successful tax lawyer in an earlier avatar, he lucidly explained the essence of a tax treaty, but sidestepped specifically mentioning Mauritius. Text messages kept coming in to journalists attending the conference, prodding them to ask the question again and clarify the Mauritius angle. The question was repeated, but once again he sidestepped

Mauritius.

However, the finance ministry issued a statement the next day clarifying that status quo prevailed on the India-Mauritius tax treaty front. It was an unusual incident where the finance ministry had to make a media statement to supplement the minister's answers. All because Chidambaram, while clarifying on the Budget, repeatedly avoided a direct answer to a question.

The episode brought out the enigmatic side of Chidambaram's personality - a side that triggers incongruous responses to him. When

Business Today polled CEOs of companies in the run-up to the budget, for instance, the largest number ranked him as the best finance minister of the five India has had since 1991. Yet the poll also said they trusted him less than the other Congress finance ministers, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and President Pranab Mukherjee. The best does not seem to be the most trustworthy.

Among all Indian finance ministers, Chidambaram, along with the late Morarji Desai, is the most experienced finance minister. His intellectual acumen is acknowledged even outside the Congress. "He is a brilliant man," says Shiv Sena's Suresh Prabhu, who was earlier power minister. "I have respect and regard for him."

Chidambaram has presented eight of India's 23 post-reform Budgets, beginning from 1991 - enough to leave a legacy. One way to dissect his legacy is to look at policymaking through the prism author Gurcharan Das likes to use. Das split economic reforms into two kinds while participating in a panel discussion on

Business Today's poll. One kind was pro-business reform which tilted towards helping favoured business groups and engendered crony capitalism. The other was oriented at breaking down cozy clubs, and dismantling entry barriers for those wishing to start a business.

In the popular perception, Chidambaram's defining moment as finance minister was the so-called 'dream Budget' of 1997. Among the proposals that year which survived the test of time was the one to bring down direct tax and income tax rates for companies and individuals. That Budget also cemented his image as a probusiness politician that Communist parties still invoke.

The Communist parties' perception of Chidambaram became clear in 2007 when they opposed his attempt to introduce a Bill to carry forward reforms in the insurance sector, particularly to allow foreign investors to raise their stake in insurance companies from 26 to 49 per cent. Communist Party of India's Gurudas Dasgupta explained his opposition to the Bill at his New Delhi residence one evening.

He first put up a series of weak arguments against the Bill, before coming out with the real reason: "We don't trust anything from Chidambaram." It was not always this way.

N. Ram, full-time Director at Kasturi & Sons, which publishes

The Hindu and other newspapers, recollects Chidambaram as being left-leaning in the late 1960s. "At that point he was left-of-centre within a broad pro-Congress framework," says Ram, who has known Chidambaram since primary school in what was then Madras. Ram says he introduced Prakash Karat to Chidambaram in Madras in 1968. "They were interested in the same issues," he adds.

Four decades on, as General Secretary of the Communist Part of India (Marxist), Karat would represent the most visible opposition to UPA's economic agenda. Juxtapose his popular image against Chidambaram's track record in the finance ministry and there is a mismatch. This is why big business feels it has reason to be wary. It is unlikely any other finance minister has so relentlessly pursued the aim of increasing the effective tax rate of companies, which is only 22.85 per cent compared with the statutory rate of 32.445 per cent. In eight Budgets, he has introduced five new taxes - the Minimum Alternate Tax (MAT), the Securities Transaction Tax, the Banking Cash Transaction Tax, the Fringe Benefit Tax and the Commodity Transaction Tax. He introduced MAT in his first Budget, in 1996, to target companies which used exemptions to avoid paying any tax at all.

According to a former finance ministry official who worked on the 'dream budget,' Chidambaram was then working to a long-term plan. First, the zerotax door was shut. That was followed by a cut in headline tax rates, which brought him applause. This was to be followed by an attempt to remove tax exemptions and push up the effective tax rate of companies. Chidambaram never got to execute the full plan as the United Front government he was part of then fell by early 1998.

He would have to wait till 2004 to present another Budget. The five consecutive Budgets he presented beginning 2004 were marked by attempts to close loopholes in the tax system and introduce new levies that would create a trail for authorities to pursue tax evaders. This aspect of Chidambaram's approach has peaked in 2013 with a Budget proposal which seeks to make evasion of excise duty beyond a certain threshold a non-bailable offence.

He has always been straight talking and gets things done: Swati Piramal

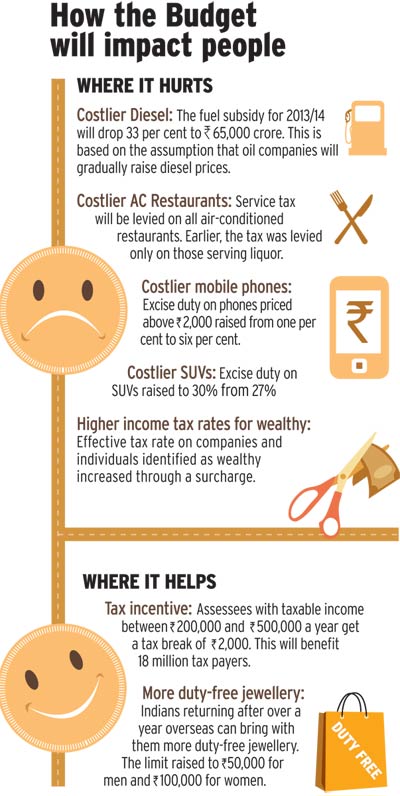

Chidambaram also does not waffle when dealing with requests from industry. Three days after the recent Budget, he met industry captains in New Delhi. Vikram Kirloskar, Vice Chairman of Toyota Kirloskar Motor, suggested the Budget proposal to increase the tax on sports-utility vehicles would hurt the automobile industry.

Chidambaram brushed aside the argument. "The buyer has a huge benefit on diesel subsidy," he said, pointing out that higher tax merely tried to offset a lopsided subsidy regime that made SUVS attractive.

It was Chidambaram who backed the tax department's decision to seek tax from Vodafone on its purchase of Hutchison's Indian telecom business in 2007. A proposal in the 2008 Budget was interpreted by Vodafone as an attempt to retroactively tax the company. The judicial dispute that followed had its moments of irony.

Chidambaram's Congress colleague, Abhishek Singhvi, represented Vodafone in the Bombay High Court in 2010. Singhvi described Chidambaram's 2008 Budget proposal as unconstitutional.

It is not as if industry dislikes him. "I have always found him accessible, willing to engage and interact with industry," says Swati Piramal, Vice Chairperson of Piramal Enterprises. "He has always been straight talking and gets things done."

Chidambaram's pro-business image has followed him to Sivaganga, Tamil Nadu, the constituency from which he has won seven Lok Sabha elections. Ahead of the 2009 polls, R.S. Raja Kannappan, the AIADMK candidate and Chidambaram's main opponent, built his campaign around this. In village after village, he rhetorically asked people if Chidambaram had ever had time for them.

"His friends are Tatas and Birlas," Kanappan said. Chidambaram won the election by a slim margin of 3,354 votes, but Kannappan later challenged the result in the Madras High Court. The case is still on.

Chidambaram's behaviour on the campaign trail in 2009 suggested he was still not at ease in grassroots political settings. His speeches to small groups of villagers stood out. The speeches in Tamil had the same characteristics as those in English - a measured approach and precise use of words in an environment where the typical political speech is overblown rhetoric. He did not make personal attacks on opponents. The typical speech would last 10 to 15 minutes and recalled his press conference tutorials. There was an attempt to link ground-level schemes to the big picture, with digressions to laud the use of boiled eggs in the midday meal scheme. Tellingly, in one village, Chidambaram asked a crowd of mostly women if they had heard of Sonia Gandhi. In short, Chidambaram the orator tried to enlighten, but was boring.

Little wonder, perhaps, that on a blistering May mid-morning during the campaign, two women following Chidambaram's speech in Arasanur village let their attention stray. They began to chat and soon drew his ire. "Pay attention," he snapped. "If I don't tell you these things, who will?" Even while seeking votes, Chidambaram is unwilling to make any effort to ingratiate himself.

Chidambaram, like every other finance minister over the past two decades, is also a fiscal conservative.

By December 2012, it was apparent that a large deficit overrun in the current financial year was unlikely despite a shortfall in tax collection and a disappointing telecom auction.

On Budget day, he said he had managed to keep fiscal deficit at 5.2 per cent of gross domestic product, compared with his self-imposed target of 5.3 per cent. The Budget was marked by a spending cut; it was finally only 96 per cent of what was originally forecast.

The cut fits nicely with his image of a fiscal hawk. It has also led to fears of a cut in welfare spending, which, in turn, feeds into his image of a friend to big business who does not mind squeezing welfare spending.

Today, even the possibility of a sharp putdown no longer holds back journalists from asking Chidambaram if he fancies himself as the next prime minister. For the record, as he told

Financial Times in January, he says the job does not interest him.

He has talked about issues which go beyond the finance ministry's mandate: Suresh Prabhu

Still, some say he pictures himself in a larger role. "The role he has assumed for himself is the role of being the government itself," says Prabhu. "In his

Budget speech he talked about a variety of issues which go beyond the finance ministry's mandate."

In some ways, Chidambaram would be an extension of Manmohan Singh. Both believe that a sound economy has to precede welfare efforts. Both are, at a personal level, understated and unfussy. According to officials who worked with Chidambaram in the finance ministry, he looks embarrassed if he is greeted on his birthday.

His son, Karti Chidambaram, says he is a master of detail. "Whether he is preparing a Budget or a legal brief or even a simple press release, he is very meticulous in his work," says Karti.

Ram, however, feels using Manmohan Singh's political career as a template to speculate on Chidambaram's future is futile. "Singh is a complete fluke in Indian politics," he says.

Chidambaram is also sharply focused on getting the job done. About 18 months ago, he was invited to an event in New Delhi to mark two decades of the 1991 reforms. At the time, court cases on the 2G telecom irregularities were threatening to consume Chidambaram and policy making in the government seemed paralyzed. Chidambaram waved away questions on whether 2011 represented the biggest challenge to any government he had been part of.

The government in 1991 faced far bigger challenges and still got work done, he said. How so? "The government did not allow itself to be distracted," was his succinct reply.

Does Rahul Gandhi agree?

Additional reporting by N. Madhavan and E. Kumar Sharma