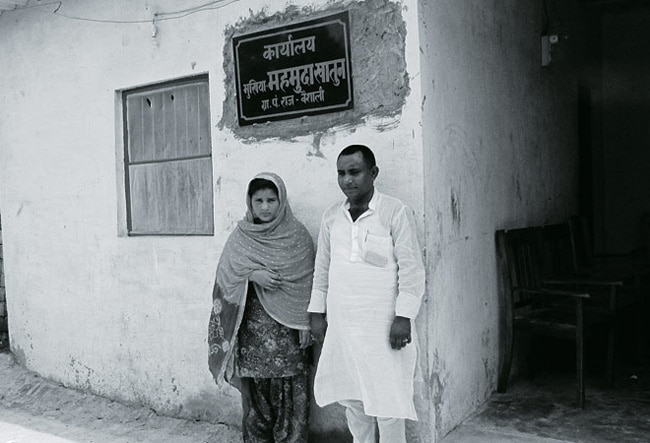

A couple of men, seated on wooden chairs, wait outside a room in a nondescript one-storied building with a freshly plastered name plate: 'Office of Mahmuda Khatoon, Mukhiya, Vaishali Panchayat'. Soon, they are greeted by a short-statured man in his 40s dressed in a sparkling white starched kurta pyjama and white canvas shoes. He listens to the concerns of the villagers about the Mukhya Mantri Kanya Vivah Yojna - it provides financial assistance to the family of the girl child at the time of her marriage - and is addressed as Mukhiyaji (chief). The man assures the group that he has verified their marriage certificate and the papers are being processed at the block office. The group is at ease interacting with Mukhiyaji. In fact, this is their seventh meeting with him for the same purpose. With much pride the man introduces himself as M.D. Kalamuddin, 'President of Vaishali, MP'.

This is not an isolated case in Bihar. As BT traveled through Vaishali district, such examples stood out. The house of Salempur panchayat's Mukhiya Neelam Devi has a similar setting. Rounds of tea have been served in the verandah where a group of men wait to meet the mukhiya. Villagers explain that a lady can't meet visitors unless accompanied by the men of the house. After some 50 minutes, a bike stops in front of the house and its driver is greeted by the group as Mukhiyaji.

A while later, Devi emerges from the house and explains the reason for her delay in meeting us. "Hum issleye bahar nahi aa rahe they kyonki sab kaam toh yehee kartey hain, toh sab jaankaari inko hai." (I was not coming out because my husband does all the work and has all the information). Devi's husband, Ram Krishna Singh, a rural medical practitioner, says his entire day goes in addressing the issues of villagers who flock to their house from morning till midnight. "Itney log aate hain ki madam ka poora din chai bananey mein nikal jaata hai. Ghar ke kaam aur bacchon ke liye bhee samay mushkil se milta hai," he says. (There are so many visitors that madam's entire day goes in making tea for them. She gets little time for household chores and children.)

Devi and Khatoon are among the scores of women mukhiyas, sarpanchs and pramukhs in the state who find themselves in a peculiar situation. They were elected after 50 per cent mukhiya and sarpanch seats (some 4,200) in panchayats were reserved for women in Bihar in 2006. But most of these women are just rubber stamps with the men in their house - it can be the husband, father or the son - running the show. A random sample of Vaishali block's women mukhiyas and pramukhs makes this evident. In Bhagwatpur panchayat, Paspati Devi is the Mukhiya but her son Nunu Singh is known to discharge all official duties. Usha Devi served as the Pramukh of Vaishali for seven years till June this year but her husband Nawal Rai, known as Pramukh Pati, did all the official work. Villagers point out that Usha Devi was hardly ever seen at the block office during her entire tenure.

Not just the villagers, but the block officials also are accustomed to interacting with the male members. In the block office of Vaishali, the official contact list of newly elected sarpanchs and mukhiyas, sourced by BT, has a column for the name of the husband, father and son. Interestingly, the contact numbers mentioned in the list are of the male members instead of the lady mukhiya. Indeed, most BDOs don't even recognise the real mukhiyas, says Anil Kumar Bhagat, a resident of Vaishali district. "In a group of women, the BDO will not be able to recognise the mukhiya. All officials are used to interacting with the Mukhiya and the Pramukh Patis," he says.

The Bihar government is aware of the ground realities in the state. In the past, women mukhiyas have been discouraged from being accompanied by their husbands, or representing them, for official meetings. Shashi Shekhar Sharma, Principal Secretary, Panchayati Raj Department, Bihar, acknowledges the problem but points out that it is not limited to the state alone. "In Jharkhand, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh men accompany and assist women mukhiyas. However, one has to look at the situation rationally. It's a structural problem. The root cause for this is illiteracy, lack of confidence and training of these women representatives," he says.

Sharma explains that the role of the panchayats has evolved in the recent past, with considerable development and financial decisions resting in the hands of the mukhiyas - right from implementing development and welfare schemes such as MGNREGA and Indira Awaas Yojna to construction of roads and drainages. These involve preparing audit reports and giving sanctions for projects. "Since the seats are reserved, women get elected. And from the very next day they are supposed to perform their duties and implement schemes and give sanctions for projects," says Sharma. "However, since most women are illiterate and do not have any training of handling technical issues and financial deals, they have no option but to take assistance from male family members. Also, family members are the only people she can trust for financial decisions."

However, that promises to be a tall order. The disconnect of the women representatives is not limited to the administrative set-up. Villagers point out that in most cases these women representatives do not even come out of the house to campaign during panchayat elections to protect the pratishtha (prestige) of the family, "Where is the question of going out for campaigning when women are still accompanied by male members while going out of the house? The lady's role is limited to dutifully filing her nomination papers and casting her vote," says Pramod Kumar Singh, a resident of the district.

Singh says women mukhiyas do not even know where the papers are filed and what documents are required. "She just signs on the nomination form brought to her. All political negotiations, decisions, bargains and approach are decided by the men." Indeed, the social set-up is such that women hardly get any time to get involved in public life. "All the household chores are undertaken by the lady and since most homes have big joint families there is no time for other activities. Middle-class women stay in purdah," says Singh.

Clearly, it will be a while before reservation of panchayat seats lead to real empowerment for these women. "Where is the question of empowerment? She has instead empowered her husband or son," says Bhagat. Villagers believe that in this milieu, it will take another couple of decades for women to contest elections independently and not as a proxy for the family.

This is also evident from the case of Kalamuddin, who had lost the election to the Bihar legislative assembly (Vidhan Sabha) on a BSP ticket in 2010 from Kurhani, in Muzaffarpur district. He then fielded his wife, Khatoon, in 2011 from Vaishali in mukhiya elections, since the seat was reserved for women. Devi's case is no different. Her family is quite influential and she was fielded for the post of sarpanch in the previous panchayat election from Salempur, a reserved seat. Devi had won, as the seat was reserved. Now she is the mukhiya. Interestingly, in Devi's case, the name and mobile number of her husband's uncle - Mohanji - is also mentioned in the official contact list at the block office.

A LOT AT STAKE

Power is increasingly being vested with panchayats for implementation of crucial schemes and projects. Indeed, becoming a mukhiya brings in recognition and power, besides being a stepping stone for a bigger role in public life. Development economist Bina Agarwal believes that both, the lure of financial resources and the political power and status which goes with the position of mukhiya, is a big draw. This makes elections to the panchayats a high-stakes battle. For instance, a mukhiya has to implement and administer 29 schemes. A panchayat gets Rs 50 to Rs 60 lakh to spend on different central and state schemes in a year, in addition to being responsible for the appointment of panchayat school teachers, Asha Health Workers and Anganwadi (government-sponsored child- and mother-care centre) workers.

In reserved panchayat seats for women, the husband or the head of the family decides and dictates the terms on which implementation of any project or scheme takes place. Kumar points out that the mukhiyas get a meagre allowance of Rs 1,200 a month and that is not the only driving force for women or their husbands to be in public life which involves working round the clock. "Since the real elected representatives do not perform any duty and all dealings are done by the husbands or sons, corruption has escalated," says Kumar. "As the block officials oblige the family members by interacting with them, therefore taking bigger cuts from the family members, it eventually translates into greater corruption in schemes."

Clearly, most women representatives have stayed at home and functioned as mere figureheads. "In many cases these women have very little or no knowledge about local governance issues. They simply put their sign or thumb impression on the dotted line," says Ranjana Kumari, Director of the Delhi-based Centre for Social Research. Bihar, and indeed India, is not unfamiliar with women running the show on behalf of their husbands. "Bihar was ruled by Rabri Devi for eight years from 1997 after her husband (Lalu Prasad Yadav) resigned following the fodder scam charges but administered the state," says Kumari.

But rampant corruption in welfare schemes has often put these women representatives in a strange position. In cases of corruption, FIRs and complaints are lodged against these women since they are the official authorised signatories but the real culprits are mostly the men. Such examples are growing in Bihar, says Minni Thakur, Reader and Head of the Department of Political Science, RNAR College, Samastipur, Bihar and author of "Women Empowerment Through Panchayati Raj Institutions". "Complaints are lodged against them and action is taken against these women representatives as they are the authorised signatory. In cases of inquiry they have no clue of what has happened and how to deal with the situation. They just follow the advice of their husbands."

Observers feel, contrary to expectations, reservation is diluting the concept of Gram Swaraj (self rule by the villages). "In the gram sabha (meeting of villagers), the mukhiya proposes all projects in front of the villagers where the plans, schemes, allocations are discussed, passed and then taken to the block officers for approval, " says Kumar.

He adds that, since the lady mukhiya does not attend the meeting, the plans are internally decided by the husbands, sons, their coterie and officials, and the lady only signs the documents. "The common man is completely kept out and is unaware of the development plans, as the sabha seldom takes place. In essence, it has weakened grassroot democracy. The only time the lady mukhiya is seen publicly is on August 15 and October 2 when it is mandatory and makes for a photo opportunity for the block records," says Kumar.

The conservative social set-up is making it difficult for women's reservation to work, say observers. "Patriarchy and illiteracy contribute to us becoming a static society in most parts of the country. Therefore, women are controlled by their fathers, brothers and then husbands. The government's schemes for empowering women are good but their implementation is pathetic," says George Mathew, Chairman, Institute of Social Sciences, Delhi.

Under then chief minister Nitish Kumar, Bihar was the first state in the country to introduce 50 per cent reservation for women in all tiers of panchayats through the Bihar Panchayati Raj Act, 2006. Currently eight states, including Bihar, have reserved half the seats in local self government bodies for women

"After the introduction of reservation, Bihar witnessed almost 10 per cent increase in voting in the 2009 parliamentary elections on account of women voters. It worked to the government's advantage. It translated into sure shot vote bank," says Thakur. While things really did not improve for the women on the ground, for the first time they got some recognition socially. "It worked as appeasement politics. The very fact that the men of the house are getting papers signed from her, she is getting some importance in the social space, is addressed as madamji and children in schools flaunt that their mother is the mukhiya, was significant," adds Thakur.

But whether reservation has actually empowered women at the grassroots is debatable.