It is a Saturday afternoon, and all lanes of Ganori village, 60 km from Aurangabad, are leading to the weekly market. The elders, in resplendent pink turbans, are having a heated discussion. The topic is local politics. They are worried. Rains have eluded the village for the third year in a row. The people are struggling to make ends meet.

Take Devidas Nagorao Dhangore, who grows cotton and bajra on his five-acre farm. When rainfall is good, he earns Rs 40,000 a year. For the past two years, he has been earning half of this. Last year, he bought seeds worth Rs 50,000 on credit. He has been unable to pay up. That's not all. Two years ago, when harvest was good, he had bought a bike. He has not been able to repay this loan either. "I need more loan but no bank is willing to lend me money," he says.

In the nearby Phoolambri village, Ajinath Tandure employs 20 labourers on his farm. In the past two years, his farm income has halved, and he is unable to pay the workers. "In good times, I had given them loans. Now, I am deducting from their salaries the money I had lent them."

Nearly 1,500 km away, in Bihar's Vaishali district, Satyendra Singh, 46, owns a five-acre farm. Unseasonal rain in early 2015 ruined his crop. "I usually produce 50 quintals wheat but got just nine quintals." He is yet to get paid even for the nine quintals that he had sold. After that, monsoons were below normal. "I spent Rs 20,000-25,000 on paddy. I am going to be in trouble." The state government promised to pay Rs 6,500 an acre to those hit by unseasonal rain but Singh got paid for just one acre. "I am still waiting for the rest." It costs Rs 30,000-40,000 to plant wheat on a one-acre farm. Singh, obviously, is far from breaking even.

The crisis is so deep that its spillover has made the whole economy anaemic. India Inc, for instance, is finding that one of the biggest engines powering it for the past few years - rural consumption - is not working anymore. It could not have been otherwise as agriculture, after all, contributes 17.4 per cent to the country's gross domestic product, or GDP, and provides direct and indirect sustenance to 49 per cent Indians.

Agriculture growth in the past one year, says D.P. Joshi, Chief Economist, Crisil, has been a paltry 1 per cent; it was 3-3.5 per cent between 2009 and 2013.

Two-wheeler makers, almost half of whose sales are directly dependent on rural demand, have been feeling the heat. Even as scooter sales grew 12.62 per cent in April-December 2015 over April-December 2014, sales of motorcycles and mopeds, whose demand is largely rural-led, dropped 3.42 per cent and 6.38 per cent, respectively. "Market sentiment in some rural areas has been impacted due to various factors, including the curtailment of rural job scheme spends, poor crop realisation and moderating wages," says a spokesperson of Hero MotoCorp, India's largest two-wheeler maker. Hero gets 46 per cent sales from rural markets, and it has witnessed around 8 per cent decline in the past year.

Tractor sales, an important barometer of economic sentiment in rural markets, dipped 15 per cent in the last financial year, according to the Tractor Manufacturers Association. In the ongoing financial year, sales have plunged 10 per cent.

Satyendra Singh of Vaishali had planned to buy an insecticide sprinkler and a tractor this year. He has deferred the plan. Punjeram Ramdas Gadve, a resident of Ghoti village in Maharashtra's Igatpuri district, is bargaining hard for a hefty discount on a 110-cc bike that he needs for moving around his 10-acre farm. He even roped in his friend so that they could get a bargain on two bikes. Gadve says he wouldn't have bargained like this two years ago. "My plan was to buy an SUV (sports utility vehicle) but unseasonal rain last year ruined my crop. I lost Rs 25,000 per acre," he says. The Hero dealer at Ghoti, Amol Mende, says he can't afford more discounts. In 2014, he had sold 1,200 bikes. In the first seven months of 2015, he had managed only 100. In 2014/15, domestic motorcycle sales had risen 2.5 per cent compared to the average of 13 per cent in the preceding five years. The year 2015/16 may be worse if we go by the current level of sales in rural areas.

Such a sharp dip in consumption is bad news for the economy as 68-70 per cent out of the country's 1.2 billion people live in rural areas. These areas account for 55 per cent consumption and one-third savings.

Sometime Ago

Rural India was booming till a year-and-half ago, especially between 2008 and 2013. According to an Accenture report, the monthly per capita spending of rural consumers rose 17 per cent between 2010 and 2012; urban spends grew just 12 per cent during the period. From tractors and specialised seeds to two-wheelers and LED TVs, rural consumers wanted them all.

"There were a lot of goods rural India did not buy much before 2000. Then, rural demand for things such as two-wheelers and anything to do with construction and personal care grew significantly," says Abhijit Sen, a former member of the Planning Commission.

Consumption patterns changed after 2004, says Pronab Sen, Chairman, National Statistical Commission. "Agriculture prices rose faster than non-agriculture prices and rural wages grew faster than agriculture prices. There was income redistribution from urban to rural areas and in rural areas from landed to non-landed," he said.

So, when Mondelez India, the maker of Cadbury chocolates, started to focus on rural areas in 2012, it started with Rs 5 and Rs 10 packs. It was surprised to find enough takers for its premium offerings, Silk and Celebrations, priced over Rs 100. "People watched same programmes, same ads, generating similar aspirations," says Sunil Taldar, Director (Sales & International Business), Mondelez India.

Policies That Worked

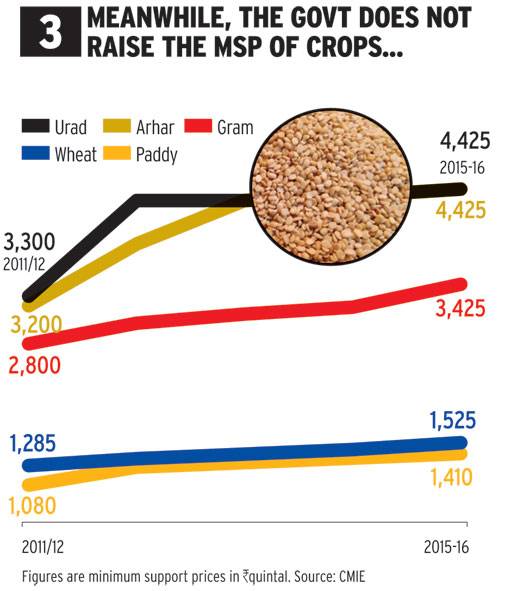

The spurt in consumption in rural areas around the middle of the last decade was not just due to the rise in farm yields. It also had to do with government schemes such as the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA) that promised to pay one person in a rural family a fixed wage for 100 days in a year. The exact wages vary from state to state, though the average right now is around Rs 170. "When MNREGA started in 2008, the wages were Rs 60 per day. Today, they are around Rs 170. That's how rural incomes went up," says Madan Sabnavis, Chief Economist, CARE Ratings. Added to this was the increase in MSP of over 9 per cent a year between 2009 and 2013. Tractor sales, as a result, rose over 50 per cent during the period. The farmers also started buying high-quality inputs such as seeds.

The period between 2009 and 2013 saw farmers going for massive upgrades, says Balram Yadav, Managing Director, Godrej Agrovet. "When prices of farm output rose, productivity became paramount. Therefore, the farmer started investing in technologies and products to de-risk his business." Therefore, if a farmer earlier bought Type-III cattle feed, priced at Rs 14 per kg, he didn't hesitate in investing in Type-1 feed, priced at Rs 24 a kg. Yadav says five years ago, Type III used to account for 75 per cent sales. Now, Type-I accounts for 75 per cent sales.

It was boom time for the infrastructure sector too. Road and other infrastructure projects required labour. This was an additional income source for the rural population.

"Two years ago, everyone was growing in rural India. People had surplus money for their aspirations. Some bought land and gold, some invested in post office savings and bank deposits. Many bought two-wheelers and second-hand cars," says Ramesh Iyer, Managing Director, Mahindra Finance, the consumer finance arm of the Mahindra Group that focuses on rural markets.

"The size of infrastructure works has reduced. Cash flows have got stretched. So, the entire consumption story has come under pressure," says Iyer of Mahindra Finance, whose profit after tax fell 37 per cent in the third quarter of 2015/16. "Contractors' payments are not coming from government agencies. So, they are unable to pay their labourers, and the surplus they have is shrinking. This is affecting their ability to service the loans," he says.

The other reason for slow income growth is fiscal restraint by the Centre to control inflation. The BJP government, according to a report by Moody's Investor Service, has kept a tighter rein on MSP than the earlier government. The report says that in June 2015, for instance, the government announced a 3.7 per cent increase in MSP for paddy, much less than the 9.1 per cent average annual rise between 2019/10 and 2013/14.

"The policies are against the farmer," says Ambas Gunaji Jadhav, a farmer from Phoolambri village in the Marathwada region of Maharashtra who grows cotton and maize. Jadhav says cotton prices have fallen from Rs 7,000 to Rs 3,000 a quintal in the last one year while maize prices have risen from Rs 800 to Rs 1,000 a quintal.

The Moody's report says that the MNREGA expenditure was Rs 36,030 crore in 2014/15, down from Rs 39,780 crore and Rs 38,800 crore in 2012/13 and 2013/14, respectively. Rajendar Ishwar, a farm labourer in Waki village in Nasik district of Maharashtra, says his wages have not risen for the past two years. The land owner, he says, pays him Rs 150 per day. This also has not been regular of late due to crop damage. He now works as an auto-rickshaw driver in Nasik and earns Rs 150 per day. "I have heard about the MNREGA but don't know what it means."

In Bihar, though a lot of villagers we met were enrolled under the MNREGA, they said money seldom reaches them. Siyaram Singh, a labourer in Vaishali district, says he is enrolled under the MNREGA but does not get either work or money. Most of the money, he claims, is pocketed by local officials.

However, Ramkumar of TISS attributes the dip in consumption to shrinking public expenditure and not just the cut in MNREGA allocation or lower MSP increases. "It's part of a larger decline in government expenditure as a share of GDP after 2011. After Pranab Mukherjee left and P. Chidambaram came (as finance minister), the austerity drive came back to the agenda. As a result, MNREGA also suffered. What you see in rural areas is the result of five years of shrinking public expenditure."

MNREGA, says Abhijit Sen, covers just 2 per cent rural population. "How much can Rs 30,000 core do for a country like ours?" he asks. He says what mattered earlier was the construction boom. "When rural incomes were growing at 6-7 per cent (real rate of growth), they (rural folks) themselves were building houses. Both urban and rural construction boom led to high demand for labour."

Changing Patterns

Fall in incomes is making people defer purchases. Om Prakash Yadav, who works as a computer operator in Uttar Pradesh's Azamgarh district, earns over 50 per cent income from agriculture. He was hoping to buy a car this year. However, with his crop getting hit, he has deferred the plan. "My wife is likely to get a job. We will probably be able to afford the loan instalments after that," he says.

Devidas Nagorao Dhangore of Kanori village in Marathwada wants to replace his 10-year-old tractor. "If rains are good and the harvest is decent, I will first repay my current loans than buy a tractor." In 2014/15, tractor sales had fallen 13.1 per cent.

Rajesh Jejurikar, CEO, Mahindra Farms, says while 2013/14 saw 21 per cent growth in tractor sales, 2014/15 was bad. In 2015, the overall market for tractors contracted 14 per cent due to deficit rains. Though Mahindra Farms registered 47 per cent growth in November 2015 due to festivals, sales grew just 1 per cent in January this year. In September 2015, the sales had dipped 37 per cent. "Sentiment plays an important role. It is decided by prospects of good monsoon, rise in MSPs, and so on," he says.

Similarly, domestic light commercial vehicle, or LCV, sales fell 12 per cent in 2014/15. J.K. Sahay, Manager, Tirhut Automobiles, the dealer for Ashok Leyland LCVs in Bihar's Muzaffarpur district, says dip in rural incomes has hit demand for pick-up trucks and mini-buses in the past one year. In the Marathwada region, dealers are reporting a 50 per cent dip in TV and fridge sales.

In these markets, such as areas around Nashik or in Bihar's Vaishali, there is a clear trend of people going for cheaper options. Harshal Kulthe, who runs a consumer electronics shop in Ghoti village near Igatpuri, also sells a plethora of local brands such as Iconic, Melbon and Hilton. Kulthe says while sales of established brands have fallen 20 per cent in the last one year, sales of local brands have risen over 30 per cent. "All the national brands are offering steep discounts, but still there aren't any takers," says Kulthe.

C.M. Singh, COO, Videocon Industries, says in 2011/12 and 2012/13, rural sales were growing 35-40 per cent. This has now come down to 8-10 per cent. "We have come up with 16-inch LED TVs priced at less than Rs 8,000 and 150-litre refrigerators for rural markets. There are no takers for these. People don't want to buy unless it is really necessary." Consumer durables sales have fallen 30 per cent in the past one year.

Such down-trading is happening across categories. Kalpana Ajinath Tandure, a resident of Kanori village in the Marathwada region, used to buy either Wheel detergent or a Rin bar to wash clothes till about a year ago. With prices escalating and her husband's income falling, she now buys detergent from the weekly market where she says she gets Wheel loose. "I have stopped stocking for the whole month," she says.

Satyendra Singh of Naamedih village in Vaishali, whose family uses personal care brands such as Lux, Clinic Plus and Fair & Lovely, doesn't want to replace these brands. "If I buy any soap other than Lux, my children start complaining," he says. So, he has started buying smaller packs.

Local Brands Ahoy!

Around 55 km from Nasik, in a village called Waki, Kiran Kale, who owns a grocery shop, struggles to sell branded items. Biscuits in the village are synonymous with Parle G and Monaco. Apart from grocery items like sugar, tea and flour, the store has a few one-rupee sachets of Clinic Plus shampoo, covered by dust. Kale says there are hardly any takers for them. "People buy biscuits only when they have visitors, but with harvest not being good, there are no takers. Shampoo used to be in demand, but not now," he says.

However, one thing that the people consume a lot are locally-packaged snacks. In fact, Kale's store hardly has any loose snacks (farsan). "Packaged farsan is more hygienic," says Rajendar Ishwar, a customer of Kale. Therefore, local brands such as Euro Chips, Officer Choice Wafers and Suder Moong Dal, which have a price advantage, do well here.

Similarly, in places in and around Bhimavaram and in parts of East and West Godavari districts of Andhra Pradesh, Meena Bakery biscuits give national brands such stiff competition due to a 15-20 per cent price advantage.

In Andhra, local brands rule the soft drinks market, too. Artos, manufactured in Ramachandrapuram in East Godavari district, reportedly has a higher market share in the region than Pepsi and Coke.

In Bihar's Vaishali, a detergent brand, Ganga Active, made in Hajipur, shares shelf space with brands such as Wheel and Ghadi and sells more than both, claim locals. The district also has a local snack brand, Njoy chips, which again sells more than Bingo and Lays.

Unsystematic Change

"Healthy development of capitalism has always been preceded by a transformation in the agricultural sector. In India, capitalism has hardly grown as the rural market is under-developed," he says.

So, the last decade's growth, say economists, was driven by a rise in government expenditure, apart from high global commodity prices that increased farm incomes. The government also started spending heavily on infrastructure, increasing rural incomes.

S. Chandrasekhar, Associate Professor, Indira Gandhi Institute of Developmental Research, says in 1993/94, six million people used to criss-cross urban-rural boundaries per day, which rose to over 25 million a day by 2011/12. "Therefore, clearly, the future rural consumption will be a function of whether India is able to invest in roads and build an affordable transport system so that people can go where jobs are available," he says.

Now, with government expenditure on infrastructure and agriculture under pressure, and global commodity prices hitting a low, rural incomes and, consequently, consumption have hit a dead end. "Rural incomes did go up, but as I said, not due to systemic transformation of rural areas," says TISS' Ramkumar.

Desperate Moves

Rural sales of Parle fell over 12 per cent in 2014. In 2015, they were flat. Other FMCG brands are also feeling the pinch. Hindustan Unilever is offering a Rs 2 discount on a 200-gm bar of Surf Excel. Santoor is offering a pack of three soaps for Rs 50, helping the consumer save `5. Parle Products has been offering extra grams in every pack of Monaco biscuits.

However, such incentives, says Dilip Patni, a kirana store owner in Phoolambri village of the Marathwada region, rarely work. He says in an environment where consumption has dipped almost 70 per cent, people don't get swayed by such offers and buy only what they need.

Mayank Shah, Deputy Marketing Manager (marketing head of the biscuits business), Parle Products, admits that deep discounting is not working in rural markets. "Rural buying patterns are different. They buy what they need, especially when the going isn't good."

Varun Berry, Managing Director, Britannia Industries, doesn't believe in deep discounts. "Most brands can afford to offer extra grams as commodity prices are low. But once input prices rise, they will have to increase prices, and that's when consumers will move away from them."

Iyer of Mahindra Finance agrees that the spell of prosperity has made the rural consumer more aspirational. "As of now, they are awaiting good times. Our role is to partner with them and not force them to repay loans when we know they can't. Today, if somebody pays us three times a month, we take money from him three times a month."

For Cadbury, growth in rural areas continues to be three times higher than that in urban markets, says Taldar of Mondelez. He says rural consumers are not down-trading but reducing the frequency of consumption.

The automobile companies, on the other hand, are merely waiting for the good times to come. Pawan Munjal, CMD and CEO of Hero Motocorp, says the dip in rural consumption has severely hit his company. "Months have passed and we have not seen double-digit sales growth," he says.

For Tata Motors, 50 per cent sales of Tata Ace and Tata Magic are in towns with population of less than 100,000. The company's spokesperson says poor sentiment in these markets has hit the entire industry. "However, with the government increasing spending on infrastructure, we are looking forward to the second half of the financial year," he says.

With large areas experiencing a rainfall deficiency of over 50 per cent, rural consumption will in all likelihood continue to be low. However, the dip that the industry is brooding over is actually restricted to less than half of rural India. Economists say rural consumption is restricted to just 45 per cent of Indian villages. The remaining 55 per cent have hardly ever had a consumption story as the big brands have not been able to reach out to this segment. "These are markets that don't have good road infrastructure. Distributing products there is fairly expensive," says B. Krishna Rao, Product Manager (head of the snacks business), Parle Products.

So, while one may blame poor monsoon or the current economic scenario for low incomes in rural areas, economists say the problem is far more deep-rooted. "We have built a weak, stunted and deformed capitalist market, and unless we do something drastic that increases incomes and, thereby, consumption, these ups and downs will continue," says Ramkumar of TISS.

With erratic rainfall becoming a way of life, Joshi of Crisil feels the government should urgently look at drought-proofing the economy.

The government indeed has to do a lot of re-thinking about rural India.

(Additional reporting by E. Kumar Sharma, Nevin John and Chanchal Pal Chauhan)