“Fair competition for the greater good.” The motto of the Competition Commission of India (CCI) makes obvious the responsibility the institution is entrusted with—make India a fair playground for doing business. Established in 2003, India’s competition watchdog took its time to evolve, learn from its mistakes, and emerge as a confident institution that not only leaves no stone unturned in creating a ‘fair’ business environment in a developing country like India, but also set benchmarks for India Inc. in terms of fair practices.

The initial journey was rough. “Initial orders were overturned in the appellate tribunal as there were a lot of procedural lapses on fairness and due process issues. CCI was admonished quite a few times; there was a rap on the knuckles from the writ courts for not following proper procedure,” says Anisha Chand, Partner in the competition and antitrust practice group of law firm Khaitan & Co. As CCI learnt from its mistakes, the number of decisions that were reversed and sent back for rehearing or reinvestigation started to fall. “This phase also witnessed courts becoming much more familiar with domestic competition laws. The quality of decision-making in the second phase improved drastically,” says Chand.

Objectives that top the agenda of CCI include preventing practices that harm competition, promoting and sustaining competition in markets, protecting interests of consumers, and ensuring freedom of trade. “Ever since CCI got legal powers in 2009, the general sentiment among the business community was that another mother-in-law had arrived on the scene,” recalls Ashok Chawla, who was CCI chairman in 2011. “It has been very much a work in progress and worldwide it has been observed that an economic regulator takes time to settle down, sometimes 20-25 years.”

Globally, competition enforcement agencies and competition laws have been in place for long. “Competition laws are new only in India. In the US, they have been there for 100 years. In Europe, laws have been there for many decades. Every country that wants to go global and wants to be respected as a state that is serious about a free-market economy has a competition regulator,” says Chand. In China, the State Administration for Market Regulation for Antimonopoly Bureau (SAMR), Denmark’s Competition and Consumer Authority, and Israel’s Antitrust Authority are a few competition watchdogs in other countries.

CCI houses six crucial divisions—combination, legal, research & trend analysis, economics, anti-trust, and international cooperation. Of these, combination and anti-trust form the central pillar of the commission. The anti-trust division monitors and acts against anti-competitive agreements and abuse of dominant position. “The officers of the division act as Case Processing Officers who prepare agenda papers and place the same before the Commission in its ordinary meetings,” says a person familiar with the functioning of the division. The combination division, on the other hand, facilitates CCI’s role as a regulator of acquisitions, mergers, and amalgamations. “This division plays a pivotal role in keeping the commission abreast of the changing business environment,” says the person.

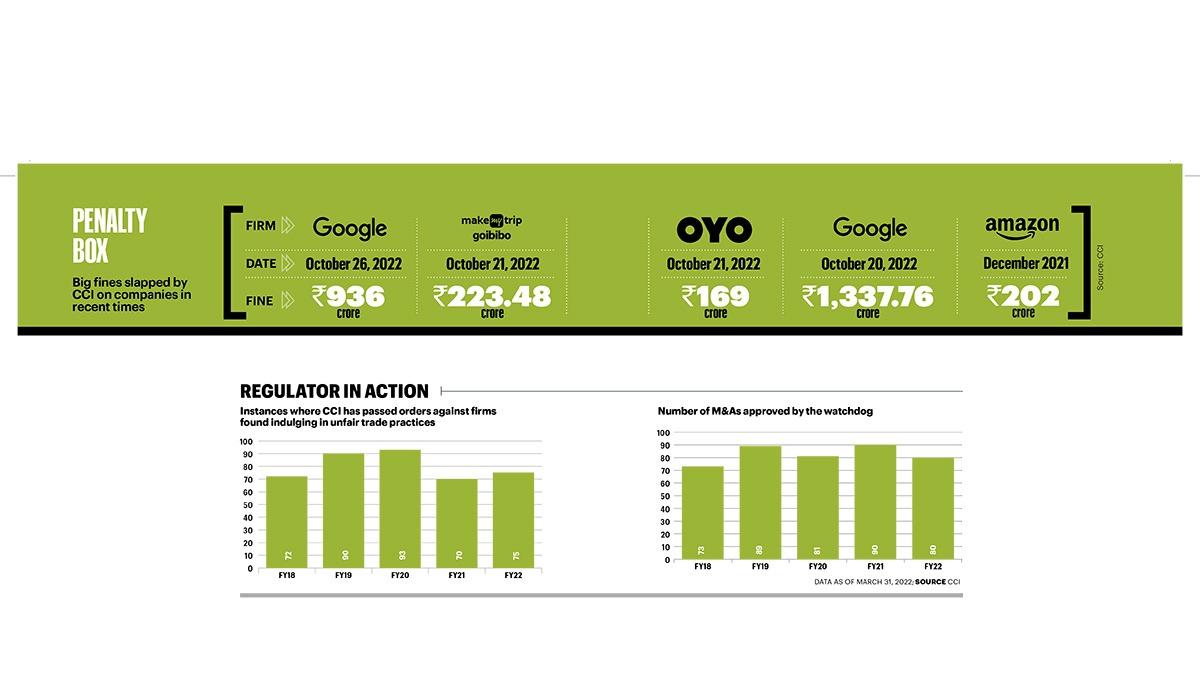

The watchdog has slapped hefty fines on tech giant Google, and hospitality firms like OYO and MakeMyTrip, among others, in the past few months. On October 20, the CCI imposed a penalty of Rs 1,337.76 crore on Google for abusing its dominant position in the Android mobile device ecosystem. The order came two and a half years after the regulator had ordered a probe following complaints by consumers of Android-based smartphones in India.

On October 21, CCI levied a penalty of Rs 223.48 crore on MakeMyTrip-Goibibo (MMT-Go) for indulging in anti-competitive practices. The watchdog opened an investigation against MMT-Go and OYO in 2019, after the Federation of Hotel & Restaurant Associations of India lodged a complaint with it alleging that MMT-Go’s hotel partners are not allowed by it to sell their rooms on any other platform or on their own online portal at a price below the price at which it is being offered on MMT-Go’s platform. In its order, CCI directed MMT-Go to modify its agreements with hotels and remove this price and room availability parity obligations imposed by it.

The watchdog on October 21 also imposed a penalty of Rs 168.88 crore on OYO for a similar reason. Challenging the order, OYO moved the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal (NCLAT), which stayed the penalty. However, while admitting the appeal filed by Oravel Stays Ltd (OYO), the NCLAT directed it to deposit 10 per cent of the penalty within six weeks. Vaibhav Choukse, Partner and Head of Competition Practice at JSA, sees non-realisation of penalties imposed as a big challenge for CCI: “The CCI has delivered anti-competition orders of wide import and imposed huge fines, but has collected very little, as most orders are under appeal and their operation has been stayed by the appellate court.”

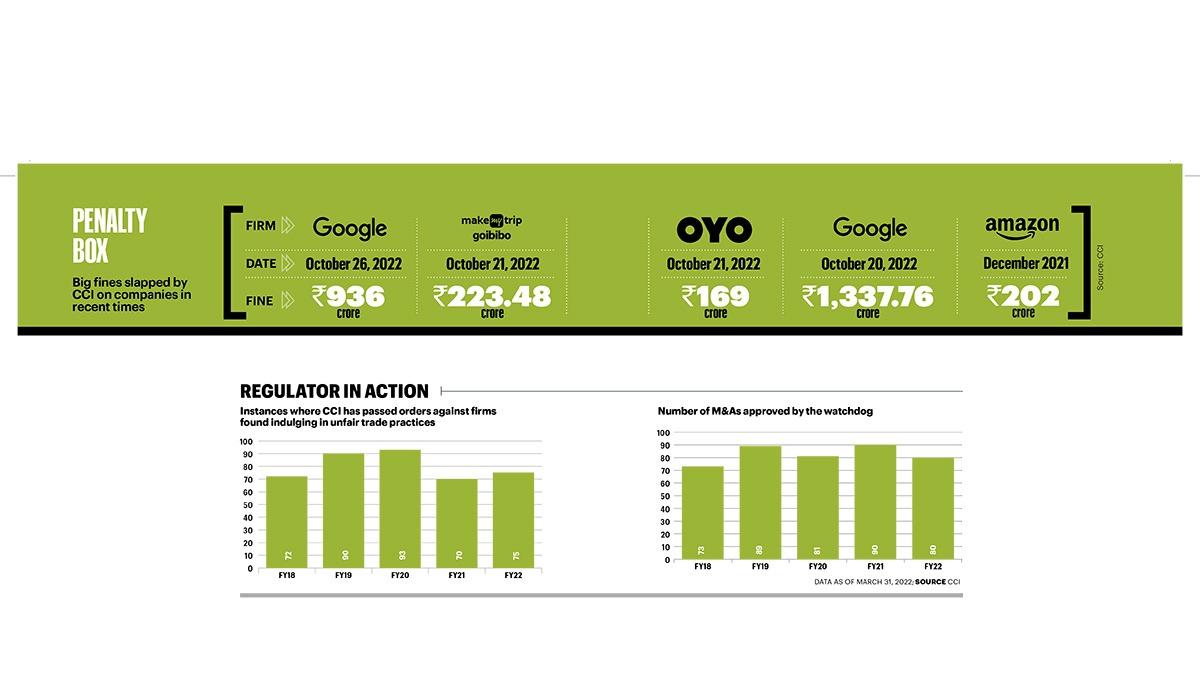

Till March 31, 2021, CCI dispatched 826 combination notices—related to M&As and amalgamations—of which 815 cases have been disposed and 11 are pending. In terms of industry, pharma & healthcare, finance and markets, and power and power generation topped the ‘charts’. In the early days, most cases were from cement cartels, real estate and brick-and-mortar firms, says Chawla, and now these have veered towards the digital segment. “As the economy changes track and grows, the nature and segment of cases also keep changing,” he says.

The Way Forward

The recently introduced Competition Amendment Bill 2022 in Parliament has opened the floodgates of regulatory developments for India Inc. From merger control to anti-trust, one can expect far-reaching changes in the competition law space. But experts say implementing the provisions of the Bill will be a challenge for CCI. “While the draft legislation seems to be revolutionary, its success finally rests on the actual implementation based largely on regulations that CCI will issue,” says Choukse.

The other key challenge, according to Chand, is a dearth of good talent and capacity. “I think the first focus should be to build capacity,” she says. “Justice delayed is justice denied. Investigations cannot go on for that long. I have cases pending from 2012-2013 because the Director-General (DG) keeps changing. So, there should be some permanent staff members who can form the pillar of institutional continuity.” In addition, the presence of a judicial member in CCI is critical. “The Delhi High Court in its judgments urged the Ministry of Corporate Affairs to ensure it, but that has not happened so far,” says Chand.

Former CCI chairman Chawla also sees capacity as a big challenge: “Capacity was a challenge [earlier] and I don’t think that challenge has been overcome. The DG takes two to three years for an investigation. Time is of critical importance.”

Going by global experience, it is still early days for the competition regulator in India. Challenges are to be expected. Overcoming them will be key to having a healthy, competitive environment in the Indian business ecosystem.

@RajatMishra9518