Resplendent in a burgundy dress by Fendi and a green-and-yellow Hermes scarf, Aditi Balbir tucks her iPad into a flaming orange Ferragamo case that costs almost as much as the tablet. "For me, it's very important to be well turned out," says the 34-year-old co-founder and director of V Resorts, with MBAs from both the International School of Business, Hyderabad, and Duke University in the US. "When I walk into a room, I want people to say, 'How cool she looks!'"

It's not just coolness. "It's the quality - once you start buying luxury brands, you cannot buy anything else," she says. The economic downturn that began in late 2008 led to luxury brands being sold at more affordable prices, and Balbir, fresh out of Duke University, started her romance with luxe.

She represents the growing segment of liberalisation-era HENRYs - High-Earning, Not Rich Yet - in India. HENRYs earn over Rs 40-50 lakh a year. Many start out by consuming luxury as an indulgence, but come to regard it as a necessity. Buying luxury is about more than appreciating fine craftsmanship - it is an affirmation of one's accomplishments to oneself and the world.

For HENRYs like Balbir, luxury brands are not just about the snob value of the label, but also about beauty and style, and a statement about their individuality.

"I am not one of those who will buy to be seen carrying a Gucci or Louis Vuitton," says Balbir. "I buy because I feel I deserve the best. I bought myself a Gucci bag when I turned 30, and it felt really cool. I have a credit running at a lot of stores at Emporio. I almost quasi-work for these companies." DLF Emporio is a luxury mall in South Delhi with 92 stores, including brands such as Canali, Louis Vuitton and Ermenegildo Zegna.

REDISCOVERING LUXURY

Luxury is, of course, not new to India, whose royalty has long been partial to custom suitcases by Louis Vuitton and custom jewellery by Cartier. In 1926, the Maharaja of Patiala gave Cartier an order to remodel his crown jewels - including a 234.69-carat De Beers diamond - into a necklace that weighed 962.25 carats with 2,930 diamonds. In the 1930s, India accounted for a fifth of Rolls-Royce's sales worldwide.

But luxury in India is no longer the preserve of old money - it is being redefined by those whose wealth has grown in the age of liberalisation. As an industry, luxury is only about a decade old in India. Luxe brands have approached the country with caution and optimism. India's demographic diversity, rich heritage and complex politics, make it a paradox.

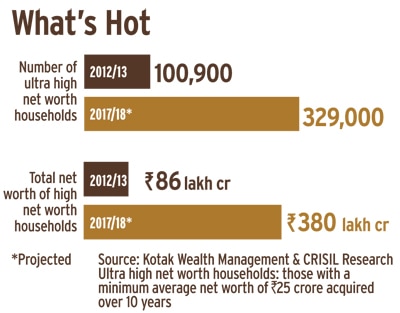

The young man has plenty of company. The number of high net worth individuals - people with more than $1 million in onshore liquid assets - in India grew 200 per cent from 2006 to 2013. Households with an annual disposable income of over $100,000 increased 60 per cent, from 700,000 in 2006 to 1.1 million in 2013.

"People are looking for the real thing... they should walk in and say this is the same store that is available elsewhere," says Mehta. The growing number of demanding consumers, who are as price-conscious as they are brand-conscious, is forcing luxury brands to move out of five-star-hotel cocoons into malls. While a couple of malls sell only luxury, hybrid malls sell luxe and premium brands. Dinaz Madhukar, Senior Vice President, DLF Emporio, says nearly 20 brands are waiting for space in the mall, which is struggling to keep up with demand. "We got some space back from Giorgio Armani for Michael Kors," she adds.

ENGAGING THE CUSTOMER

Emporio opened in August 2008, nearly a decade after India got its first luxury brand, Ermenegildo Zegna, and just a month before Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy. The mall, with gold-plated taps in the washrooms, ginger lily fragrance, dedicated concierge desk, huge crystal chandeliers and tasteful window displays, was not how India shopped. Initial reactions were polarised.

Emporio's 'Treasury of Trousseau' show in August let customers meet designers such as Manish Arora, Rohit Bal and Tarun Tahiliani by appointment, for personal consultation. "We want to make every individual comfortable - we don't want anyone to feel intimidated," says Madhukar. DLF Emporio got calls from Chandigarh, Ludhiana, Hyderabad and Pune asking about the festival. Also going to great lengths to engage the customer is Genesis Luxury, a company that pioneered luxury retail in India and has brought in labels such as Burberry, Jimmy Choo, and Bottega Veneta. It has 47 stores for 14 luxury brands in five cities - Delhi, Mumbai, Bangalore, Hyderabad and Chennai and is now eyeing Kolkata.

Sanjay Kapoor, Managing Director of Genesis Luxury, says his company tracks the preferences of every customer who has ever walked into one of its stores. He says: "Our system has a record of every buyer or browser and his preferences. We know what a certain customer bought last year at a Canali store in Bangalore, and hence can connect his preferences by showing him the appropriate merchandise in New Delhi at Emporio."

Personalised service, festivals, promotional strategies such as providing expenses-paid holidays or giving away cars to select buyers during the 'low season' (typically the summer months) are all part of the larger effort to engage with customers at the individual level. Emporio's customers can also saunter across to the DLF Promenade mall next door to browse premium brands, and buy, say, a Zara dress.

MILES TO GO

India's luxury industry is set to grow at 25 per cent a year between now and 2015, according to an ASSOCHAM-YES Bank study. However, compared to China, India has far to go. China's luxury car market is nearly 30 times bigger, and the luxury watch market in mainland China alone is 15 times larger. At $6 billion, India's luxury market is a fourth of China's $25-billion one. India has about 70 luxury stores, while China has over 1,000. Italian retailer Ermenegildo Zegna has more stores in China than all luxury brands put together in India.

"China's at a level where it determines global sales," says Tikka Shatrujit Singh, Advisor, Louis Vuitton India. "China determines investment policies of every brand." Culturally, too, the Chinese don't have a living heritage to influence their tastes - their imperial past was wiped out in the Cultural Revolution - giving luxury marketers a clean slate. And an evolved retail infrastructure has helped things along. "We are 10 to 12 years behind China," states the Bain report.

The Indian market, on the other hand, faces several challenges. Most luxury brands in India have margins of 35 to 40 per cent. But they are squeezed by exorbitant rents and lack of quality retail infrastructure. DS Luxury, which brought Tom Ford to India in 2010, continues to take a hit on margins as its Director, Ritesh Kumar, grapples with steep rents. "Rents are as high as those in Europe," he says. "DLF is not quoting anything less than Rs 1,500 per sq ft."

Currency fluctuations are like salt in the wound. "We can't pass on higher costs to consumers, because that might affect sales," says Kumar. "We plan to hedge currency from next year, if rupee depreciation continues."

While most luxury companies temper enthusiasm with realism, they clearly express optimism about the Indian market. Luxury goods, however, continue to sell at prices 30 to 40 per cent higher than in some other markets. Customs duties in India are high - 30 per cent - which is more than double those in Dubai. The product range in Indian stores is limited, and new seasonal collections take longer to get here.

As a result, many Indians still call that friend or aunt in London for a quick price check - if the price is much higher in India, the purchase might wait till the next London trip. However, Emporio's Madhukar points to a subtle but important shift: "People are shopping for a vacation to London, as against taking a vacation to shop in London."