O big Tata

You lent your fire and our iron you took

The shades of Mahua trees you took

(Folk poetry from areas around Jamshedpur)

Commercial production of the much-touted Rs 1-lakh car was to start in October, but looks virtually impossible now. As Business Today went to press, the possibility of Tata Motors moving out of West Bengal lock, stock and Nano appeared very real.

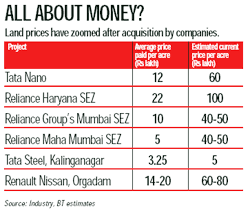

Yet, Singur is just one troublespot for the highly-diversified Tata Group, which has a clutch of other companies in its stable that is hungering for growth. Just one of those companies is Tata Steel, which is seeking to put up a 6-million tonne, Rs 22,000-crore steel unit in Kalinganagar in Orissa. The company is also seeking to build a port in Dhamra on the Orissa coast. As if the Singur showdown wasn’t enough last fortnight, at the annual general meeting (AGM) of Tata Steel in Mumbai, the 70-year-old Chairman had to contend with belligerent activists who were also shareholders. The object of their ire isn’t too different from that of the Singur protestors—Tata is apparently using land that, well, it should not be using for industry.

Tata cajoled these Greenpeace members to agree to meet B. Muthuraman, Managing Director of the steel giant, on September 10. When one activist insisted that Tata himself should be talking to Greenpeace, the Chairman threatened to unleash the company’s lawyers on the group. By then, it was the turn of other shareholders to get into the act. A few of them were keen to know the status of the steel plant in Kalinganagar.

The Tatas have been facing violent protests in that region for the past two years. That’s when Tata summed up the huge predicament staring not just the Tatas in the face, but some of India’s biggest businessmen: “The issues at Singur and Kalinganagar are different. However, whether you want to build an industrial unit or mine for ore, you have to do it on agricultural land—and that is an issue we have to deal with.”

The list is long, but as estimates by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) indicate, of the total investments of Rs 70 lakh crore planned in the country, projects worth a massive Rs 2.5 lakh crore are facing resistance in acquiring land. It’s an alarming situation—alarming enough for Mukesh Ambani, in late-August, to speak out on behalf of the Tatas.

And also on behalf of all other mega-projects that are stuck (including his own). “A fear psychosis is being created to slow down certain projects of national importance. This will be counterproductive for the country’s economic growth, its global image as well as our ability to attract investments from across the world. Indian industry and the political leadership in the country need to work together to deliver on the aspirations of the millions of Indians in urban and rural areas,” said Ambani.

Simmering in Singur

Not for any sum of money,” declares Proshanto Singha, a local farmer, pointing a finger over the western wall of the Nano plant. Singha can’t do much since the project site is manned by a large police force, but warns ominously that he will support didi’s (Banerjee’s) agitation at the site.

Tata Motors, of course, says it needs all the land as one block not just for the main plant but for ancillary units, too. Cut to Orrisa. At least two big projects, of POSCO and Anil Agarwal’s Vedanta Resources, are stalled because of hurdles in land acquisition.

Vedanta’s Indian arm, Sterlite Industries, wants to mine bauxite reserves in the Niyamgiri hills in the Kalahandi district of Orissa. The metals giant has already built an alumina refinery at the foothills, and has got the go-ahead from the Supreme Court to mine on the hills. The problem?

Pramod Suri, Head of Aluminium Business at Vedanta, reiterates what Chairman Agarwal told shareholders in London in July. “Without taking the people into confidence we cannot mine the area. We have to explain how we will improve their life.” Suri says Vedanta is already working on bringing electricity to 20 villages in the region and working on a project to eradicate malaria. “The Supreme Court took three years to deliver its judgement on the issue after looking at every aspect of protecting the environment. The kind of mining that we will do has been done by Nalco for 25 years. We will not start mining at 20 spots at the same time; and as soon as we vacate an area we will reforest it.”

Still, in Orissa, Korean steel major POSCO is also up against a confrontational local populace. The development of its proposed 12 million tonnes per annum steel plant near Paradeep Port will need all of 4,004 acres. As Vishal Dev, Chairman, Industrial Development Corporation of Orissa (IDCO), points out: “Only 436 acres (of that land) is privately-held; the rest is government land, and now the Supreme Court has even given the project environmental clearance.”

But that hasn’t quelled the protests. The anti-POSCO movement has spread across villages. Abhay Sahu, Chairman of the POSCO Pratirodh Sangram Samiti (PPSS), says the village of Dhinkia will lose a third of its area to the proposed plant. The erudite Sahu contends that he is not against industrialisation.

“But this is fertile land, and the betel-vine (paan) that are grown here provide a ready source of money and employment. While the vines grow on government land, they have been here for centuries. There are 3,000 vines in the village area, and each vine provides Rs 1 lakh of income every year.” Then, there’s Tamil Pradhan of Nuagaon, another village affected by the POSCO project.

Pradhan is a leader of the United Action Committee (UAC) formed by the villagers to support the plant and to bargain for an R&R package. He explains that the villagers were against the project initially. “But now, we are already seeing some benefits. Land prices are rising, and people are making plans based on the plant. It will be a disaster if the plant does not come here, but at the same time the compensation must be good.” The current status, however, isn’t encouraging for POSCO. Construction, which was supposed to start earlier this year, is nowhere near beginning.

“We haven’t been given possession of any land as yet,” says S.K. Mahapatra, General Manager, Human Resources & Public Relations, POSCO-India. “We will only start acquiring land once our R&R package is cleared by the government.”

Another promoter who has a lot riding on a sound R&R package, and policy—some Rs 70,000 crore on two SEZs—is Mukesh Ambani. He is is building the twin SEZs named Navi Mumbai SEZ and Mumbai SEZ covering almost 25,000 acres of land. The Mumbai SEZ, in Raigad district on the outskirts of Mumbai, is being built by privately-owned companies and Anand Jain’s Jai Corp. To ensure contiguity in the Mumbai SEZ, the Maharashtra government notified the acquisition of 20,285 acres of land in 45 villages of Pen, Panvel and Uran Talukas in Raigad District. Of this, about 5,000 acres have already been bought by the company on a “willing-buyer willing-seller” basis, but resistance from farmers has made the going tough. “It’s a challenge,” is how Jain, Chairman, Jai Corp, which has a 10 per cent stake in the project, put it to BT recently. “We are not moving any of the 45 villages in the SEZ and these people will be the first to benefit,” he adds.

A big worry for industrialists is that once a project is delayed, it can stay stuck for a decade and more. Utkal Alumina, a project that started off as a joint venture of Indian Aluminium, Canadian Alcan and Norwegian company Norsk Hydro, has made no headway in Orissa for almost 12 years.

Reason: hostile land owners. Last year, the Aditya Birla Group took over total ownership of the joint venture. Says a spokesperson of the Aditya Birla group: “There were problems related to land before we took over the project. Now, there is little problem.” Brave words those, but reports suggest that Chairman Kumar Mangalam Birla met the Chief Minister of Orissa, Naveen Patnaik in July, to discuss the R&R issue.\

There are no easy answers to these high-stake stalemates. Whilst landowners would seem within their rights to preserve their way of life, industry inevitably will have to trample on agricultural land in its quest for growth. Somewhere between these two extremes there has to exist a middle path. Compensating landowners in true free market style may be one answer. Outlining a clear R&R policy is an imperative for the government.

Eliminating speculative middlemen from the process of land acquisition is another. And corporations need to spend some thought on winning the confidence and support of the local populace before venturing blindly like pillaging land-grabbers. In the next few pages, Business Today attempts to analyse the lacunae in policy measures, and also delves into some of the successful cases of land acquisition by promoters.

Additional reporting by N. Madhavan