It takes Kenichi Ayukawa five seconds of chuckling and seven seconds of hemming before he begins to answer the question. The question itself was innocuous. What is the one thing that he would like to bring over from Suzuki's Pakistan operations, which he headed for four years before joining

Maruti Suzuki India last April as MD and CEO?

He takes time to make his pick. It is not the environment ("er… very difficult country, politically"), or the market ("business-wise quite difficult, regulation not easy"). Nor is it the scale ("very small"). However, over there in Pakistan, Ayukawa knew his people, much smaller in number, much better. He would like to have the same kind of human relations in India.

Maruti Suzuki , he says, is too big. "Sometimes I do not know who is who and cannot recognise some of my people when I meet them in the city."

Prey to PredatorEvery morning Ayukawa first goes to the factory in Gurgaon, whose gates open to a dusty and noisy road, before coming to the corporate headquarters in Vasant Kunj, New Delhi, a stone's throw from a bevy of shiny malls. The visit to the other factory in Manesar, about two hours away by road, happens once a week.

Soon after joining, he surprised everyone by walking into a meeting of the workers' union, something few MDs are known to do. Were there any awkward moments?

"I was comfortable," he says. "Face-to-face meetings are important. You can see the person's eyes and [sense] how he feels. Gradually, with a smile, things change."

At the meeting he talked at length about the state of the company: sales, financials, and the market situation. "We are in the same boat. We are not enemies. We are colleagues and have to collaborate. That is why we have to share information. The direction should be the same for everyone, which is, growth and development of the company. If we get the right results, the fruits can be shared."

Each of those words strikes the right note. For, the people issue has pegged Maruti back in recent times more than market and policy vicissitudes.

July 18, 2012, was a dark day in the company's otherwise proud history of three decades. Someone died that day: Awanish Kumar Dev, General Manager of Human Resources. He was killed by the same workers he used to look after, and command and cajole, every day at the Manesar factory. His charred body was discovered late in the night.

At least 100 other managers were injured: broken arms and bleeding heads were the most common injuries. Some hurt themselves as they jumped off the first floor to avoid rampaging workers, who took whatever they could find - tools lying about in the factory, parts of the cars they used to put together, hinges pulled off doors - and did things they had never seemed capable of doing. What's more, the darkest hour came on the back of a prolonged labour unrest the previous year, which had caused an estimated loss of Rs 2,500 crore in revenue.

The company began to buckle under the fresh assault. The Manesar plant was locked out for almost a month. Maruti's share of the passenger vehicles market plunged to nearly 38 per cent, a far cry from the vertigo-inducing 55.5 per cent in the year 2000. Net profit after tax fell 5.4 per cent in the July-September quarter of 2012.

The labour trouble came in the midst of a wild swing in the market towards diesel cars. "After April 2011 the share of diesel cars rose from about 36 per cent of the total sales to 58 per cent. We did not have enough diesel capacity, only the one plant in Manesar producing 200,000 diesel engines. We had a waiting list for 100,000 diesel cars but no capacity," says Chairman R. C. Bhargava.

Competition began to snap at Maruti's heels. Hyundai had always been a formidable challenger, albeit always a distant second. Toyota gained ground with its Etios and Liva, both of which mostly sold diesel variants. In the ensuing months, things got worse as Honda launched the Amaze, a small diesel-powered sedan striking at Maruti's core of DZire. Renault-Nissan was getting ready to storm Maruti's bastion of small cars (A segment) with its Datsun brand. Tongues began to wag: how long could Suzuki, a minnow in the global automotive order, continue to dominate a market where the whales had come in?

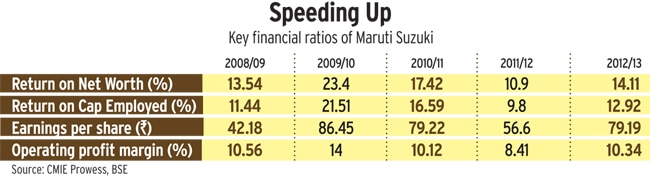

The opposite has happened. Maruti's sales have grown 1.3 per cent during April-November, while the market has shrunk 5.6 per cent. In December, car sales fell 4.52 per cent, but Maruti's rose 5.5 per cent, giving it a market share of 41.3 per cent for the nine months of this financial year. Osamu Suzuki, patriarch Chairman of Japan's Suzuki Motor Co, which holds 56.2 per cent equity in Maruti, has told his managers in India to keep it above 40. All the financial indicators are going up.

"The EBITDA margin had dipped to seven per cent in 2011/12, our worst year. It is now 12 per cent. We don't want it to fall below 10 per cent," says Ajay Seth, the finance head. EBITDA is earning before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation - a key indicator of financial health.

The company has pulled off a coup by doing away with contract workers, who were seen to be at the root of the unrest at Maruti and several other manufacturing companies. It has moved to a system of hiring workers who would be laid off if the demand went down and the company had to reduce production.

A buoyed Maruti is now gearing up to take the battle to the enemy camp. On the anvil, according to Bhargava, are two sports utility vehicles to get a foothold in the market that Renault's Duster and Ford's Ecosport are running away with. The SX4, its old warrior in the mid-size sedan segment that looks like a very tired old warrior, is ready to be replaced. At the biennial Auto Expo starting February 7, it will unveil a car with auto gear shift technology, which has gears similar to automatic transmission and does not engage the clutch, but delivers the fuel efficiency of manual gears.

There is a modern research and development facility being set up in Rohtak in Haryana, which will design, develop and test new vehicles for India and some overseas markets. Spread over 700 acres, it will be bigger than the Manesar factory (600 acres) and more than twice the Gurgaon factory (300 acres). The capital expenditure earmarked for it is Rs 1,500 crore over two years.

We have brought the import content down from 30% to 16%. Our target is 11-12 %: Ajay Seth, CFO, Maruti

"All the testing for future models can be done there. We can do the complete PDCA cycle: plan-do-check-action," says C. V. Raman, the head of engineering and R&D. There is no other facility in India to match it, only Tata Motors' can be spoken of in the same breath. Raman says it would be the best in Asia, and better than anything Suzuki has in Japan since all the learning from there will be incorporated at Rohtak.

The centre will help Maruti develop vehicles just the way the Indian customer wants it. Once it is fully functional, Raman and his team of 1,300 engineers will move there. For context, when Raman joined the engineering wing in 2001, it had less than 100 engineers.

Overall, the company has put aside Rs 5,000 crore for Gurgaon, Manesar and the new factory to be set up in Gujarat. In a presentation made at the Tokyo Motor Show last November, Suzuki talked about 14 new models for India, "the most critical region", in four years.

"We should not be defending, we should be attacking," says Ayukawa. "We have accepted [keeping market share above 40 per cent] as a challenge."

All the testing for future models can be done there (at Rohtak). We can do the complete PDCA cycle: plan-do-check-action: C. V. Raman/ Head of Engineering and R&D, Maruti

A November 25, 2013 report by Credit Suisse says Maruti is the best placed carmaker in India on the parameters of suitable products, sales and service network, India as an export base, brand strength, ownership costs, and commitment to India. Under the sub-head, Maruti: Almost flawless execution, it says: "It is also developing a small diesel engine for its A segment cars where none of its key competitors has a diesel offering. This smaller diesel engine will also be used by the company for its foray into the LCV segment. Another thing that should help drive both volumes and help Maruti better combat currency volatility is the decision by Suzuki to allow Maruti to develop export markets in Africa and Latin America."

Getting into a better position to cope with the market swing, it has set up new capacity for 150,000 diesel engines a year at Gurgaon. The plan was to set up another 150,000 in the second phase, but that has been put on hold for now.

For good reason: diesel prices have been on the rise, narrowing the gap with petrol. The result is an 11.5 per cent drop in sales of diesel cars during April-November last year, while petrol car sales rose 3.3 per cent.

There is a fierce localisation drive going on. "We have brought the import content down from 30 per cent to 16 per cent. Our target is to bring it down to 11 to 12 per cent," says Seth.

Equities research firm Anand Rathi said in a report of January 9 that it expected Maruti to report 38.6 per cent higher profit in the quarter ended December 2013. Some of it would come from the merger of Suzuki Powertrain, the company that owned the engine and transmission facility at Manesar, with Maruti.

However, the story of how Maruti morphed from a defender into an aggressor goes beyond hard-nosed facts. To truly understand it, you need to do what Ayukawa is doing: get to know the people who make the company what it is. And it will be a candid encounter, for these men do not hesitate to share their deepest secrets, sanguine in the belief that no one among their competitors has what it takes to do what they are doing. So what does it take?

Pareek took a two-year 'sabbatical' from home. Five years later he is still on 'sabbatical'.

When Mayank Pareek told his wife about taking a two-year sabbatical, she was not happy. This was not a sabbatical from work but from the duties at home. Pareek had realised that his company, Maruti, needed all his energy as it prepared to face a slowing economy. The wife, to his immense relief, was supportive.

That was five years ago. He is still in the sabbatical. In this period, the share of the rural market in Maruti's total sales has grown from a mere 10 per cent to more than 30 per cent, as the total has grown from about 800,000 vehicles to nearly 1.2 million.

In the meantime, Pareek, Maruti's COO-marketing and sales, has become an expert in areas with which few corporate COOs can claim even a nodding acquaintance. He can talk with aplomb about priests, granite polishers, dhaba owners, teachers, farmers and gram panchayats.

We are counting each drop... As much as 4.8% of our sales are in villages with less than 100 households"

Mayank Pareek

COO/MARUTI

It is knowledge gained on long road trips. During one of them he met a petty shopkeeper in Dhanbad who said the slowdown was only for those who read The Economic Times and watched CNBC.

An enlightened Pareek told his team to pay no attention to what they read and saw, to be aware but not become victims of the news. And he set out to find customers who would not bother much with the slowdown.

Last September while travelling in Gujarat he noticed several outlets along the highway which were bigger than dhabas but smaller than motels. He stopped to talk to the owners. It turned out they raked in Rs 1 lakh every day. Once back in office, he devised a special package for them on the Omni van, which has space to carry goods. The package gets steady sales of three to four dozen every month.

On a drive from Bangalore to Coimbatore he noticed a number of granite polishing units. These were doing well despite the slowdown. There is a special package for them now.

He asked his team at a brainstorming session which section of society did well during bad times. The answer was temple priests, who receive more offerings as people pray more. Maruti now has a special package for priests, which started at the Trimbakeshwar temple in Nashik.

To counter the rising interest rates, he looked for customers who did not want to buy on loan. Typically, farmers like to pay in cash. There is a special package for them.

Pareek also loves government teachers in villages. They draw more or less the same salary as their counterparts in the cities, but a teacher's monthly expenses in Orai would be a fifth of a teacher's in Lucknow. Maruti's guru dakshina programme reaches out to teachers.

The income from NREGA is not enough to help its beneficiaries in the villages buy cars, but they do end up buying soap, detergent and toothpaste. That puts more money in the pocket of the shopkeeper, who becomes a potential car buyer.

All told, Maruti has 332 special packages for small and niche customer segments, each of which buys 30 to 50 vehicles every month. "Every drop counts," says Pareek. "We are counting each drop and these are adding up to something big. This year our sales growth is 1.3 per cent, but the rural market has grown more than 18 per cent."

There are two things that encourage rural folk to buy Maruti's cars more than ever before. First, road connectivity in villages has improved vastly in the last few years, thanks to the Prime Minister's Gram Sadak Yojana. The second is the company's network of Resident Dealer Sales Executives (RDSEs), an army of 7,743 that covers 93 per cent of India's 3,854 tehsils. These are men and women drawn from the local population. Surveys had shown that village people did not really trust English-speaking attendants in shiny showrooms. RDSEs collect data and sell cars, each of the two functions equally vital to the company.

Pareek has a fat log book. A swish of its pages can tell you that village Sasa in Gujarat's Saluja tehsil has 10,000 people, three government schools with a combined 24 employees, a primary health centre with six employees, branches of Dena Bank and Canara Bank, and 10 farmers with land holding larger than 10 acres. The village has 400 two-wheelers and 40 tractors but just five four-wheeled passenger carriers. Pareek's eyes light up by the time he reaches that last bit. "As much as 4.8 per cent of our sales are in villages with less than 100 households. Last year we sold our cars in 46,000 villages. A large number, you might say, but that is just seven per cent of total number of villages in the country. Our mission this year is to raise that number to 100,000."

Maruti has set up 500 new sales and service outlets in small places in the last five years, adding to its already formidable network (see Here, There and Everywhere). It has started a Maruti Mobile Service, which will come to your house in a village to service your car. There will be a thousand of those by the end of this year.

What the Eye Can SeeM. M. Singh has been with Maruti for 30 years, the last 10 as head of manufacturing. He is a much respected figure on the shop floor. But this was too much. Having observed the conveyer belt in the engine assembly at the Gurgaon factory, he said it was stopping every now and then. The plant manager refused to believe him. As far as the eye could see, the line was running smoothly. Singh told him to install a counter on the conveyer and report the findings in a week.

The plant manager came running to him after three days. The conveyer, he said, was pausing 800 times every day: only for a fraction of a second, but it was pausing all right. The problem - related to tightening of nuts and fool proofing - was fixed and the output went up by 20 to 30 engines a day without anybody even noticing the change.

"I have images in my mind of all the parts of our factories. I can see what others do not. You have to involve yourself to that level," says Singh, in a manner so down to earth that he seems incapable of grandiloquence.

This ability to see has made Singh a popular speaker at corporate conferences, where he gives out his secrets without fear. "Nobody can replicate us. By the time they get to where I am, I will have moved to another level."

The levels indeed change fast. Every year Singh exceeds his cost reduction target. It was Rs 351 per vehicle for April-November last year, but he had touched Rs 628 by the middle of December. Before you scoff at the figure, multiply it by the annual production of 1.2 million. The total manufacturing cost has fallen nearly 40 per cent in seven years.

When Maruti introduced the K series of engines in 2008/09, its tool cost - a key indicator of production cost - worked out to Rs 185. Singh said he wanted it brought down to Rs 22, which was the tool cost for the old engine. In five years it has come down to Rs 25. (The old engine, though, has moved to another level at Rs 13.)

The guiding principle at the factories is that the machine and the conveyor must not be made to wait. O. Suzuki is known to say that nobody should be paid for walking. Moreover, if a worker walks 20 steps to get to a component bin, that is 40 steps for each component. If his shift produces 200 cars, that is 8,000 steps for him, leaving him exhausted.

I can see what others do not. You have to involve yourself to that level: M. M. Singh, Head of manufacturing, Maruti

So the components have been brought closer and closer to the assembly line worker, not an easy task given the layout of car factories. The walk is now a tenth of what it used to be a few years ago. In some cases, there is no walking needed. In these cases, Singh has moved to a new level, monitoring the bending and lifting by each worker. Components are now placed to his left and right and as much as possible at a comfortable height.

There are meters installed all over the factories to measure electricity and water consumption for each car. During the two tea breaks of 7.5 minutes in each shift, the assembly line is stopped and all lights switched off, leaving only the tea shacks lit up. "It is in our DNA to switch the lights off when leaving the desk," says Seth, the CFO.

Most of the components now move from one place to another without consuming electricity, they simply slide on pulleys and rollers. In some cases this gravitational pull-fuelled system starts right where the component suppliers offload their trucks.

For two months every year, starting February, Singh works seven days a week. On Sunday he prepares a list of things he wants to achieve the next financial year. The other days he holds sessions with workers, supervisors, engineers and managers telling them about his plans. They, in turn, get back to him with suggestions and ideas of their own.

Last financial year, Maruti saved Rs 350 crore by implementing suggestions made by the rank and file. Most of it was the small things. For example, the company used to pay a supplier Rs 734,000 every year for the seal of leak testing machines. The seal is now made in-house and the bill is down to Rs 130,000.

"The workers have understood that if we are to survive we have to be cost-effective and the best in quality, that they will do well if the company does well," says Singh. But what if they get other ideas, as they did at Manesar in 2011 and 2012?

Taking strife out of LabourThe Gurgaon factory has been free of labour trouble for nearly 14 years. However, Manesar has been a different story; it was even a different company: Suzuki Powertrain India, which was merged with Maruti in 2012/13. It also had its own system of recruitment, conducted through two external agencies.

The workers stayed in small, rented accommodation, often four to a room, and had nothing to do after work. Manesar also had a high percentage of workers provided by contractors, over 50 per cent as per some estimates. The workforce there was new to the company, its age profile young. In consonance with the ambition of their generation, they were restless.

That was in contrast to Gurgaon, where many of the workers have been working for 20 years or more and take pride in their uniform, which gives them a high status in their villages. The large number of seasoned workers in Gurgaon kept the ambition of the young in check. "Your time will come," they told their juniors.

Manesar did not have such a calming influence of seniors.

It does now, to an extent. About 150 senior workers from Gurgaon, who lived near the Manesar factory, have been transferred there. Still, the average age of Manesar's 4,800 workers is 29; for Gurgaon's 7,200 it is 35.

There is a lot more happening. "We have done away with the recruitment companies and the contractor. We have gone back to the system we had in Gurgaon. We do a complete background check - we look at where the candidate comes from, how is his family. Candidates are first taken as apprentices and watched for a whole year. The apprentice then takes an examination and is selected as trainee for two years. The most important thing is the attitude," says Chairman Bhargava.

A portion of the recruitment is being done under a new system. If there is a fall in demand, some of them will be retrenched. The person who joined last will be the first to go. If the demand picks up, the guy laid off last will be the first to come back. All regular workers' vacancies will be filled from this cadre, unless somebody turns out to be a bad apple. "The idea is to keep them and give them the motivation of becoming regular workers," says Bhargava.

Eventually, the new system will account for about 30 per cent of the total workforce, which is also the percentage of demand swing that occurs every once in a while.

"Unfortunately our law does not have a provision for temporary workers. You do want flexibility in the workforce because demand is flexible. So people take contract workers and the system gets misused," says Bhargava. "We do not want hire and fire, we want temporary workers. What we also need in India is some kind of social security system."

Some other companies, too, are beginning to embrace this system. "There is no other way," says the human resource head of a financial services MNC.

In the first decade and a half of its existence, Maruti had facilitated housing for its workers in the nearby villages of Chakrapur and Bhondsi. Over 2,000 houses, all owned by workers, were constructed. The company now wants to revive the system.

Talks are on with the Haryana government for flexibility in building laws so a large number of high-rise buildings of small units can be constructed. "That is the way to lower the cost for each worker," says Bhargava. Maruti will help them get land, finance, architects and contractors.

And MD Ayukawa is not alone in facilitating communication with workers. All senior managers are bonding with their underlings. Workers representatives are sent to Japan to understand the systems there.

"I never questioned my father. But both my sons and both the daughters-in-law question me. They also question their mother-in-law. In our time, the mother-in-law's word was law. If things have changed so much at home, they must change at the factory," says Singh.

So he and the other senior managers often tell the workers how the company is doing, how the market is doing, the triumphs and the tribulations. "You have to get them involved," says Singh. "Once they feel involved, they can produce unthinkable results."

He has numbers to back his belief. Many would think of Rs 350 crore saved through workers' suggestions as unthinkable.

{mosimage}What If

Maruti can do well in the short term but the longer term may prove more challenging. Given the bottom-heavy structure of the Indian market, by 2020 it is possible that Maruti may be able to retain its signifi cant volume share of the small car market given its traditional positioning and/or lack of interest from global majors.

It's hard to predict the future. However, Maruti's share of revenue and profi tability is likely to face high pressure because the high-volume, low-price segment barely generates any profi t in absolute terms, even after taking into account Maruti's depreciated asset base.

Can Maruti fi ght a global player in the long term? It is possible that Suzuki could change the paradigm in India. However, in no other market has it been able to effectively compete with the likes of Toyota, Ford, Volkswagen and Hyundai.

Suzuki's withdrawal from the large car market in the United States, its lack of signifi cant presence in the premium small car market in Europe, and its marginal position in the emerging car market in China, indicate it struggles to compete in markets where global majors have a focused presence.

It has performed well only in the small car markets of India and Pakistan during decades when global majors did not show much interest.

What if Toyota or Ford were to deploy the strength of their global resource base to compete in India?

If success is survival, Maruti is going to be all right. If success is thriving...

Vikas Sehgal, Managing Director & Global Sector Head - Automotive, Rothschild

For full version go to businesstoday.in/maruti-sehgal

|