Everybody loves a gift. That’s the basic principle for businesses looking to build a customer base or entice existing customers into spending more. And it also holds true for elections in India, where political parties go all out to bring in votes by promising schemes and incentives that can run into a few thousand crores of rupees, if not more, that eventually come out of the taxpayers’ pockets.

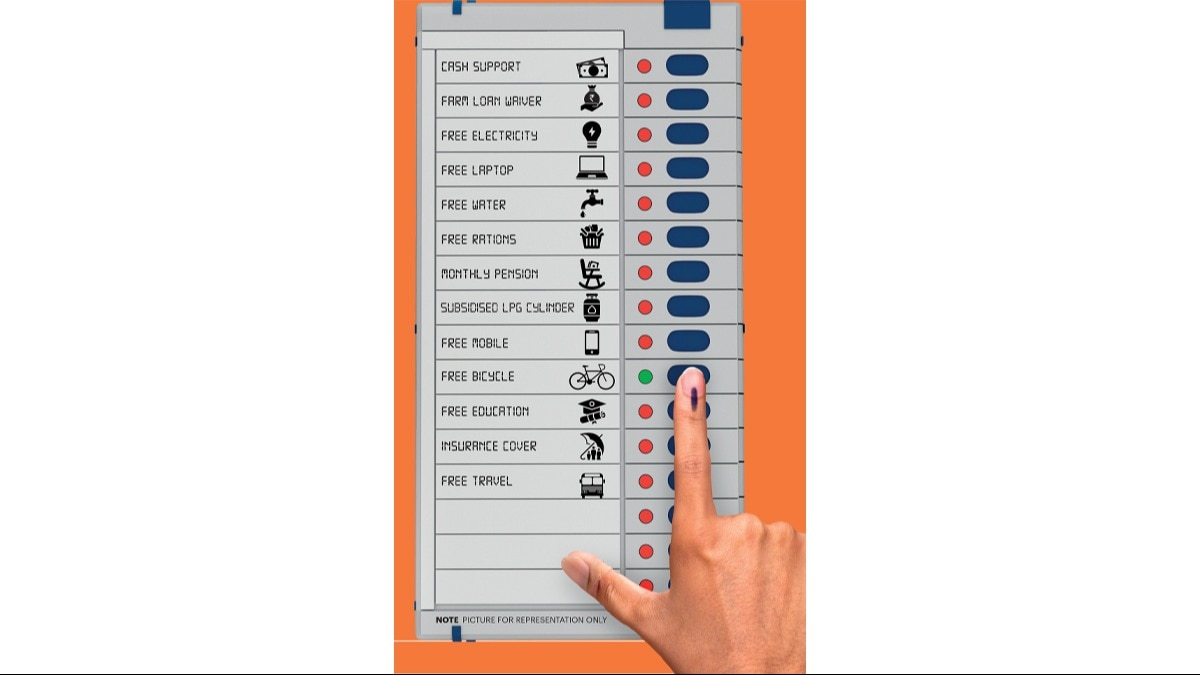

Not surprisingly then, the recent state elections saw promises of doles and new schemes flying thick and fast. From farm loan waivers and government jobs to free education, higher cooking gas subsidy, financial packages for women, laptops for college-going students and reverting to the Old Pension Scheme (OPS), political parties left no stone unturned in trying to win voters during the recent assembly elections in the states of Mizoram, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Telangana (see chart ‘On Offer: A Reading of Poll Promises’). Prior to that, assembly elections in Uttar Pradesh and Karnataka also saw such promises.

That’s not all. Bowing to popular demand, the government had as part of the Union Budget 2023-24 set up a four-member committee led by Finance Secretary T.S. Somanathan to review the New Pension Scheme (NPS) for government employees. More recently, the central government has extended the free food grain subsidy scheme by another five years at an estimated cost of Rs 11.8 lakh crore.

The stage is now set for the General Elections in 2024 and the state polls are expected to help political parties assess how far the promises of freebies helped them in getting votes. For instance, the freebies offered by the Congress in Karnataka are seen to have contributed to its win, while the BJP’s Ladli Behna Yojana is seen to have given it the edge in Madhya Pradesh.

While election freebies are not a new trend in Indian elections, the issue has become hotly debated in recent months. There have also been concerns raised on such largesse in recent years as the central government and the states try to become more fiscally responsible, while the finances of many states remain under pressure after the Covid-19 pandemic. There is also a growing realisation that the cost of these schemes has to be eventually borne by the voter, often in the form of higher taxes.

Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman had raised the issue at a recent election rally in Telangana. She noted that freebies are being announced across many states without taking their financial feasibility into account. “False promises are being made and political parties promote them but when it comes to the allocation of funds, they backtrack,” she had underlined. Earlier, even Chief Election Commissioner Rajiv Kumar has voiced concerns over this phenomenon.

Despite the Centre’s strict adherence to fiscal deficit targets in the previous years and Prime Minister Narendra Modi questioning the freebie culture—especially after the debt crisis in neighbouring Sri Lanka—economists remain wary about higher government spending ahead of the General Elections in 2024, although for now it seems that the central government’s fiscal deficit goal of 5.9 per cent of GDP will be met and it will remain conservative in its spending. “Competitive populism has remained a dominant theme in state elections, not just with the Congress, but also the BJP,” brokerage Nomura has highlighted in a recent report.

Investors were worried that a poor showing by the BJP in the state polls would increase the risk of more fiscal populism, the Nomura report says, adding that a BJP victory across most states does not necessarily reduce the likelihood of competitive populism recurring as a dominant theme in the 2024 General Elections.

Experts also note that often the exact fiscal impact of election-time promises on taxpayers may only be felt after about 12-18 months of the government being formed, by when the schemes have been fully implemented. Though the cost of such promises is often hard to gauge, a recent report by SBI Ecowrap on the Arithmetic of the Karnataka Budget estimated that almost Rs 60,000 crore annually would be required to fulfil the five pre-poll guarantees of the ruling dispensation.

“For the current fiscal (rest of the year), it is estimated that Rs 35,000-40,000 crore is required to fulfil the guarantees, a part of which was already accounted for in the FY23 budget. In effect, the subsidy has been increased by Rs 14,500 crore in FY24, compared to the FY23 Revised Estimate primarily due to enhanced subsidy for energy and food supplies,” the report notes.

There are also a number of cases with the Supreme Court on the issue. For instance, in October this year, the Supreme Court issued notices to the Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan governments, the central government and the Election Commission on a plea seeking comprehensive guidelines to bar political parties from distributing cash and other freebies at the expense of taxpayers.

What is a freebie? While there is no definition as such of what constitutes a freebie, economists believe that any measure that does not have a long-term impact on development can be categorised as one. These can be anything from farm loan waivers to free laptops.

According to a recent report called State of State Finances 2023-24 by PRS Legislative Research, subsidised items can be broadly classified as merit and non-merit goods. “The consumption of certain goods and services such as education and health by an individual may have wider benefits for the society and the subsidisation of such goods can be considered socially desirable,” it says. However, providing subsidies for non-merit goods may not involve wider social benefits, the report notes, pointing out that in 2022, the Reserve Bank of India had also observed that increasing expenditure on non-merit subsidies can constrain the space for capital expenditure.

N.R. Bhanumurthy, Vice Chancellor of Bengaluru-based Dr. B.R. Ambedkar School of Economics University, notes that there is a need to differentiate between freebies and social sector measures announced during polls that can have a long-term development impact. According to him, farm loan waivers have limited impact on consumption demand, but in the long term, have negative implications on the fisc and limit resources for other important social sector expenditure. “It is a freebie as it does not have a long-term impact on growth and development, or on productivity,” he says.

However, a free bus service for women, as has been promised in many states, can have medium- to long-term implications on the female labour force participation rate. Similarly, the extension of the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PM-GKAY) will help address the nutritional status of the poor and their productivity. “Freebies add to the public debt burden. From day one, they impact the regular budget, public debt and the fiscal deficit. They do not add to the GDP in the current or the future period,” he adds.

Sacchidananda Mukherjee, Professor at Delhi-based think tank National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP), notes that it is the government’s discretion on where to spend, but there is a need for a cost benefit analysis of such measures to households. Some of these such as food subsidy or employment guarantee can be recurring expenditure, while others such as those on providing laptops and phones can lead to a one-time spike in expenditure. “It is important to note that some subsidies such as those on electricity and water can free up spending in households that can then be used for consumption and lead to higher revenue for the government as well,” he says.

Mukherjee’s recent analysis has found that the 18 major and nine minor states faced fiscal stress in the Revised Estimates of 2022-23. “Given the experience of revenue mobilisation and expenditure management in 2022-23, states [should] adopt a cautious approach in setting the Budget Estimates for 2023-24,” says his paper called State Budget Analysis of 2023-24: State of Indian State Finances.

The PRS report also highlights that several states continue to budget revenue deficit, thus constraining capital outlay. The outstanding liabilities or accumulated debt of states has also risen again in recent years, partly due to expenditure, such as farm loan waivers and debt takeover from the UDAY scheme. In 2020-21, states’ fiscal deficit limit was increased to 5 per cent of GDP due to the adverse impact on revenue receipts because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Outstanding liabilities of states were estimated at 29.5 per cent of the GSDP at the end of 2022-23 as against 26.7 per cent at the end of 2019-20.

Over the past several years, states have spent close to 8-9 per cent of their revenue receipts on providing subsidies. States can provide subsidies on various items such as electricity, public distribution system, education, health and transportation. Subsidies form a part of revenue expenditure, which is used for largely non-capital formation items such as payment of salaries, pensions and interest liabilities, and dominates the Budget expenditure. On the other hand, capital expenditure tends to be lower but is used for capital and asset formation. Typically, high revenue expenditure is frowned upon and most governments focus on increasing capital expenditure, as is being done now, in order to boost growth. Higher subsidies can often mean a need to review the capital spending.

“A significant portion of such subsidies are spent to provide subsidised or free electricity. Concerns have been raised over rising subsidies for non-merit goods in several states. Providing such non-merit subsidies may constrain the fiscal space available for capital expenditure,” says the PRS report authored by its researchers Tushar Chakrabarty and Tanvi Vipra. For instance, as much as 97 per cent of Rajasthan and 80 per cent of Punjab and Bihar’s total subsidy outlay went towards subsidising electricity in 2021-22.

The report has also analysed the benefits of the recent trend on financial assistance to women and notes that of the five states that are implementing or have announced cash transfers for women, all except Madhya Pradesh have budgeted for a revenue deficit in 2023-24 (see box ‘Cash Support’). “Cash transfers to women can improve their bargaining power within households. However, implementing such large-scale cash transfer schemes without rationalising existing subsidies and benefits may increase the revenue expenditure of the governments,” it has cautioned.

There are also widespread concerns about the fiscal impact of reverting to OPS or even a hybrid pension scheme that would benefit state and central government employees who joined service after 2004. Recently, a few states like Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Punjab and Himachal Pradesh have announced a reversal to the OPS from NPS. “Internal estimates suggest that if all the state governments revert to OPS from NPS, the cumulative fiscal burden could be as high as 4.5 times that of NPS, with the additional burden reaching 0.9 per cent of GDP annually by 2060,” RBI says in its latest report, ‘State Finances: A Study of Budgets of 2023-24’. This will add to the pension burden of older OPS retirees whose last batch is expected to retire by the early 2040s and, therefore, draw pension under the OPS till the 2060s, it warned.

The RBI report also highlights that states’ total outstanding liabilities are budgeted to fall to 27.6 per cent of GDP for 2023-24 from the peak of 31 per cent in 2020-21; however, the debt to GDP ratio could exceed 25 per cent as at end-March 2024 (BE) for 25 states and union territories. However, the overall fiscal outlook for the states remains favourable in 2023-24, it adds.

However, do these issues really matter to the Indian voter, many of whom are still struggling to make basic ends meet and the tantalising promise of a government job or free mobile phone seems too good to pass on? A recent report by Bank of Baroda that studied the socio-economic profile of the five states where polls were held in November says that their economic and social profiles are very different from one another. “It may be stated upfront that economic elements may not have a significant bearing on the election outcomes,” it says.

M. Govinda Rao, Emeritus Professor at NIPFP, Chief Economic Advisor of Brickwork Ratings, and a member of the 14th Finance Commission, notes that electoral budget cycles are a phenomenon that exists in all democratic systems. “People look for short-term benefits and governments want to win elections by giving them at the cost of long-term growth-enhancing expenditures... People want benefits now though this will burden the future,” he says.

While redistribution is a legitimate function of governments, Rao notes that it is important to realise that it involves opportunity costs. “Even when redistribution has to be done; it is better to give cash transfers than giving subsidies to avoid relative price distortions,” he advises.

Apart from the General Elections, next year will see more states, including Andhra Pradesh, Odisha, Haryana, Maharashtra and Jharkhand, go to polls. Populism is likely to take centre stage in these elections, along with issues like inflation (especially in food prices), jobs and demands for a caste census. But with the focus on capital expenditure and fiscal prudence, political parties may have to maintain a fine balance between fiscal profligacy and vote-bank politics. That could be a tightrope to walk.

@surabhi_prasad