It was a close shave for the passengers and cabin crew aboard SpiceJet's flight SG 1085 on March 8. It took off as scheduled from Bangalore's Kempegowda international airport for Hubli around 6 p.m. but soon ran into rough weather. Just before landing, a downpour and thunderstorm engulfed the aircraft. It appeared to lose balance and wobbled through the runway with a damaged left maingear before skidding to a halt.

While it was a miraculous escape for those on the Bombardier Q400, also called turboprop, the damage to the aircraft was beyond repair. SpiceJet discontinued its operations to Hubli thereafter.But the crash of the turboprop had an unexpected outcome. In May, Gurgaon-based SpiceJet posted its first net profit - of Rs 22.51 crore - in eight quarters. A major contributor to the bottom line was the income - Rs 61.35 crore - that the airline earned from the insurance claim on the damaged aircraft. "It is part of life. Sometimes, we pay to insurers and sometimes, we get from them," says Ajay Singh, Chairman of SpiceJet.

Indeed, Singh has been working tirelessly to nurse the airline back to health since his takeover earlier this year. His hands-on approach has led to the gradual improvement in market share, passenger load factor (PLF or the number of seats sold as a percentage of seats available) and financial performance in recent months. However, the challenges in front of SpiceJet are still daunting.

The Problems

SpiceJet was stumbling from one crisis to another for the past three years. Its losses mounted to Rs 1,003 crore in 2013/14, leading to a crippling shortage of cash to pay off debt and dues. Then, in December last year, it was the last straw. The airline was grounded after oil companies refused to refuel its aircraft due to non-payments. Singh, who had started the airline in 2005 before selling his stake to Kalanithi Maran in 2010, stepped in immediately. After getting speedy approvals from the government, he acquired 58.46 per cent shareholding in SpiceJet from Kalanithi Maran and Maran-owned Kal Airways Private Ltd in February 2015.

Singh didn't invest a penny out of his pocket in the airline until he had a fair idea of the challenges before him. Singh nearly camped in the SpiceJet office in Gurgaon for weeks doing due diligence and taking stock of liabilities. Once he had made a detailed assessment of the airline's problems, he devoted time to convincing the government about his Rs 1,500-crore revival plan. "In December, the DGCA (Directorate General of Civil Aviation) passed an executive order asking SpiceJet not to make advance booking of tickets. It is like the Reserve Bank [of India] saying this bank is going to fail. It was a sure shot way of making an airline collapse," Singh recalls.

After taking over SpiceJet, Singh has been trying to improve the on-time performance (OTP) record of the airline. Still, the airline fares poorly on the OTP parameter in four metros - Delhi, Mumbai, Bangalore and Hyderabad. In May and June, its OTP stood at 72.1 per cent and 60.2 per cent, which was the lowest among domestic carriers. IndiGo, in contrast, had an OTP of 80.2 per cent and 82.6 per cent in those two months.

Singh says a low OTP can be attributed to the three planes that it took on wet lease from Czech charter airline TVS. These planes came on board for a short period to meet the rising passenger traffic during April to June. Wet lease is a leasing arrangement whereby an airline or lessor provides an aircraft, crew, pilots and maintenance to another airline. "Our turnaround time is 25 minutes. They go by their rules. Their turnaround time is 45 minutes," he adds.

Rising from the Ashes

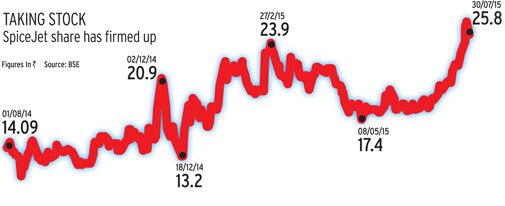

Singh, however, is turning things around on various fronts. Take market share, for instance. Between July 2014 and February 2015, SpiceJet's market share dropped every month, sliding from 20.9 per cent to 9.2 per cent. But it has picked up in recent months, touching 12.1 per cent in June.

The airline has also shown marked improvement in its PLF rate. In May and June, the airline recorded the highest PLF - 93.1 per cent and 93.2 per cent, respectively - among domestic airlines. But PLF rate can be misleading, say experts. Airlines can easily boost it through flash sales. For instance, SpiceJet has done around 11 flash sales since January, including a July offer of tickets priced at Rs1. "Such sales are part of the low-cost carrier (LCC) business. LCC is like an Udupi hotel in the sky. If you keep prices low, load factors increase," says G.R. Gopinath, founder of Air Deccan.

However, experts say there's nothing wrong with such a strategy. "An airline knows its historic PLFs for different seasons. If they can plan now, and set aside a small percentage of seats in a [future] lean season for flash sales, they can increase the PLFs without making losses," says an aviation analyst.

Flash sales would not account for more than four to five per cent of total available seats, Singh had told Business Today in March. For SpiceJet, it would also help in restoring customers' trust in a brand which was tarnished because of large-scale flight cancellations some months ago.

"For an airline to come back so quickly and be profitable in a weak quarter and fly with 90 per cent load factors is a very unique occurrence in the aviation [industry]," says Singh.

Take-off Troubles

Even as the airline gets back into shape, there are challenges galore that could delay its recovery. To begin with, SpiceJet is struggling to induct new aircraft in its fleet. Its current 34 aircraft fleet includes 18 Boeing 737s, 14 Bombardier Q400s and two wet-leased Airbus A319.

Following its crisis in December, three lessors - Wilmington Trust SP Services, Babcock & Brown Aircraft Management, and BBAM Aircraft Leasing and Finance - dragged the company to various courts seeking to de-register their (Boeing) planes with SpiceJet due to payment defaults. Once de-registered, the airline can't use those planes.

According to Singh, out-of-court settlements have been reached with all three lessors. "During this [first] quarter, we have reinducted an aircraft that had previously been returned and are in discussions to reinduct few more, which reflects renewed lessor confidence in SpiceJet," SpiceJet's CFO Kiran Koteshwar said in a statement during the second quarter results. SpiceJet has returned almost 20 planes to lessors over the past year.

Nevertheless, the whole incident has made lessors more cautious. Gopinath says the issues with lessors have given bad reputation to India and SpiceJet, in particular. "It will take time for the new management to prove its credentials," he adds.

Under the Cape Town Convention, to which India acceded in 2008, the lessors should be given repossession of aircraft in case of payment defaults by an airline. For example, in the case of Kingfisher Airlines, airport operators seized aircraft because the company owed money to them. "In India, they don't make repossession easy. They go to courts. They also remove parts. Once the aircraft is stuck in the country, the lessor loses money. The convention says that if the airline cannot pay, you first return the aircraft, and then make an account settlement," says Gopinath.

Last year, SpiceJet placed orders for 42 Boeing 737 Max planes, which will start arriving from 2018. The company is trying to prepone the deliveries to 2017. Then, there are reports of the airline buying 100 new planes from either Boeing or Airbus as part of its long-term plan.

Singh says that he could not anticipate that the aircraft availability would become a challenge in the short term. "When we went to the market, the aircraft were not available. My anticipation was that because of the troubles in Russia and some other places, there would be more planes available. Unfortunately, there seems to be more Airbus available than Boeings," he says. It is generally difficult to get aircraft in the short-term. Most orders are placed three to five years in advance.

A Thorn in Side

Nearly three months after joining the airline in 2010, the last SpiceJet CEO Neil Mills placed orders for 15 Q400s. He was confident that compact turboprops would make sense for an airline looking at expanding its footprint. First, only a limited number of airports in India can handle narrow-body aircraft (A320s or B737s). Turboprops can be operated on smaller airports where big planes can't land. The previous management thought that they would be able to tap into regional demand, connecting small towns with short-haul flights to metros like Chennai, Delhi and Hyderabad.

Also, the government policy encouraged induction of smaller aircraft. It was a diversion from the global LCC model of having single-type aircraft fleet, which keep financial and managerial complexities down and operations simpler.

The management soon realised that they required two sets of pilots, engineers and cabin crews. It also meant different contracts and additional cost of maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO).

With renegotiations, the overall costs for turboprops have come down by 10 to 12 per cent. "It has to come down more. We are halfway through. If we get the costs down to exactly what we want it to be then we can even add more aircraft. Otherwise there's a still question mark over it," says Kapoor.

If nothing works out, the last resort for SpiceJet would be to sell these turboprops in the secondary market.

An aviation industry analyst, Ameya Joshi, says with dual-type fleet, SpiceJet can get more PLF by connecting smaller cities with metros and in turn feeding into their metro-to-metro network. "They now have a workforce trained on the Q400s along with considerable number of pilots, crew and engineering staff," he says, pointing out to global LCCs like Flybe, WestJet and Allegiant Air don't have one-type fleet.

Back to Basics

There are other problems for SpiceJet. The airline has not focused on building a network over the years. In a typical LCC model, every destination should have a reasonable number of flights (per day) so that the fixed costs get amortised.

Similarly, for an aircraft, more seats translate into lower unit costs. Even if an airline is flying more passengers, the staff salaries and equipment costs are fixed for each station. That's why most LCCs have maximum seats allowed in an aircraft.

Some years ago, SpiceJet started opening too many stations with only one flight a day such as Mysore, Indore, Bhopal and Pondicherry. Last year, the company started relooking at its network with an aim to consolidate the number of stations and increase frequency between them.

The Future is LCCs

Meanwhile, things are looking up for LCCs again, and players like SpiceJet are likely to benefit from it. A recent report by CAPA says that the industry's financial performance is expected to improve further in 2015/16.

The market share of LCCs in the aviation industry is set to rise to over 70 per cent in two years, from 65 per cent currently. IndiGo's domestic market share will almost certainly cross 40 per cent during 2015/16 and could cross 45 per cent within the next two years. In such a scenario, it would be interesting to see how SpiceJet makes an effort to regain market share without compromising on profits.

Full service carriers (FSCs) are putting up a good fight. Indeed, according to a recent study conducted by regulator DGCA, there was hardly any difference in fares of FSCs and LCCs in 2014 on some routes. For instance, in the last quarter of 2014, SpiceJet's average fares for a Delhi to Mumbai flight were higher than that of Air India, IndiGo and GoAir.

This year has been spectacular for the industry with passenger traffic growing at 19.81 per cent during the January to June period as compared to last year. The drop in fuel prices allowed airlines to offer discounted fares through a series of flash sales to rev up demand. "Intense competition in domestic market led to frequent flash sales in 2014/15 that created a sudden spurt in traffic. An improvement in overall business sentiment in India also helped," says Amber Dubey, Partner and India Head of Aerospace and Defence at KPMG.

Experts point out that even though the domestic passenger traffic has nearly halved between April 2011 to March 2012 (121.51 million) and January to December 2014 (67.38 million) the market leader IndiGo has managed to increase its market share in the same period. For instance, its market share has grown from 23.8 per cent in April 2012 to 38.4 per cent in June this year.

"Whenever an airline goes down (Kingfisher or SpiceJet), IndiGo tends to benefit because of its consistency and scale," says an aviation analyst.

In fact, IndiGo is the only airline that has become profitable in the past four years. Its closest rival GoAir is also profitable but with a much smaller operations - only 19 aircraft. IndiGo, on the other hand, has about 96 planes and is adding about 10 to 15 new ones every year.

The competition is also likely to intensify in the LCC market with the launch of two regional airlines - Air Pegasus and TruJet.

Overstaffed

The rise of IndiGo coincided with the fall of SpiceJet. The SpiceJet management went overboard with staff hiring till the end of 2103. At one point, SpiceJet had employed some 140 employees per aircraft as compared to about 100 for IndiGo. It's an important metric to look at because the moment an airline breaches the 90 employees per aircraft ratio, it is seen to be overspending on staff salaries which can affect profitability. Clearly, the new SpiceJet management realised that it has to prune its staff strength if it is to become profitable.

Overstaffing took its toll on SpiceJet. Its employees eventually were not paid salaries on time last year, leading to mass exodus of pilots and cabin crew. Singh says that staff rationalisation was his top priority when he joined the airline. In 2014, the airline had 5,500 employees. "When I took over, it had already gone down to 5,000. Currently, we have about 3,800 people. After laying off over 1,000 people, our staff rationalisation plan is almost complete," says Singh.

But that was not enough. Singh also assessed the performance of senior staff who were hired by the previous management at "exorbitant" salaries. For example, SpiceJet's former VP (revenue management) Fares Kilpady was reportedly paid over Rs2.5 crore. Recently, seven senior personnel have quit the company.

There are talks of more pruning at the top. "I have to do it gradually at the senior level. I cannot create a vacuum all of a sudden," says Singh.

The Long Road Ahead

SpiceJet needs to quickly start generating profits because its promoter cannot continue pumping in money. So far, Singh has put in around Rs850 crore, which is significantly short of the amount - Rs1,500 crore - that he had planned to invest initially. Singh says the money is arranged by him from banks, trade finance, creditor finance and his own funds. Singh, who owns around 59.13 per cent stake in the carrier, has recently pledged 34.04 per cent of his stake, as per the July 17 filing to stock exchanges. He is also planning to infuse another Rs300 crore in which he will accommodate some private equity (PE) players who have not invested in the airline so far.

Recently, there were reports that Gulf carriers such as Qatar Airways and flydubai are in talks with SpiceJet to pick up a stake. Both airlines, however, have denied any discussions with SpiceJet. "We have also got offers from some foreign carriers to participate but I think it is at premature [stage]. PEs have not invested for the reason that the company didn't need cash as urgently. They bring strategic value to the company. We will take a call on the timing and the amount," Singh says.

With some stability in operations, SpiceJet is now trying to move up the value chain. It has launched three ancillary services recently -Spice Assist, priority check-in and bag-out-first.

Also, it has refocused on its premium product - SpiceMAX - that mostly caters to corporate travellers. SpiceMAX seats come with more legroom, priority check-in and complimentary meals and beverages at an extra fee of Rs500 to Rs1,000. Corporate customers spend higher amount than leisure travellers.

"The successful LCCs make 15 to 20 per cent of their revenues from ancillary sources. We just reverted to our original strategy of trying to increase the ancillary revenues. We also aim for 15 per cent target," says Singh.

The current off season is, perhaps, the ideal time for Singh to draw up a long-term strategy for network, pricing, fleet and staff. "Raising funds of about $200 million is critical to effective and executable long term strategy. A new SpiceJet has to emerge post December 2015 which has a clear strategic direction," points out CAPA's Kaul.

For Singh, the journey has just begun.