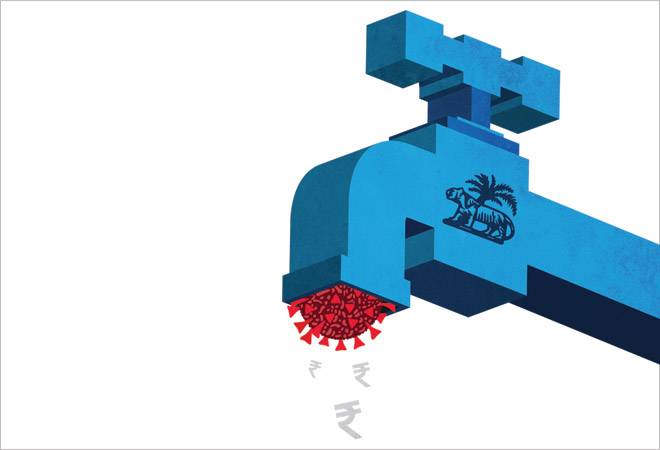

Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Governor Shaktikanta Das said in a recent interview that banks were not willing to take credit risk beyond a point. The reason: The Rs 3.74 lakh crore surplus liquidity was not reaching those hit hardest by the current crisis - non-banking financial companies (NBFCs), microfinance institutions (MFIs), micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) and mutual funds.

In fact, there was no dearth of liquidity in the banking system even pre-Covid. Risk-averse bankers were happily depositing funds back with the RBI and earning risk-free returns. The bankers retort was, why should one take credit risk in a slowing economy? Similarly, when over Rs 1 lakh crore was pumped in by the RBI to encourage banks to buy corporate bonds, bankers invested the money in PSU bonds, and made a killing. Outsmarted twice, the RBI is now reviewing the situation before deciding its next course of action. Das' words carry a subtle message - the Centre needs to step in urgently to create confidence among banks to lend. Companies are gasping for funds, and left to fend for themselves, may go bankrupt.

But not everyone agrees. "This is an unconventional war on the economy. A traditional blanket liquidity measure will not work as some will not get the benefit at all, while some others may get more benefit," says Arun Singh, Chief Economist at Dun & Bradstreet. "The risk capital in the system is very low. The surplus liquidity will not naturally convert to either lending beyond a particular risk profile or investing beyond a particular risk profile," says Suyash Choudhary, Head (Fixed Income) at IDFC AMC.

Credit Risk: The Hurdle

"The RBI is fighting risk aversion across segments in financial markets," says Arvind Chari, Head (Fixed Income & Alternatives), Quantum Advisors, an asset manager for institutional, high-networth individuals (HNIs) and retail investors. Sure enough, the problem has been there for long. It first surfaced five years ago, when gross non-performing assets (NPAs) of banks reached 9 per cent. Public sector banks (PSBs), which account for two-third of the banking system, were suddenly unwilling to lend to sectors like construction, real estate and infrastructure. The collapse of IL&FS led banks to withdraw from NBFCs too. Suddenly, private banks also switched focus from large corporate loans to safe retail segments and MSMEs. Even investors such as mutual funds, insurance companies and HNIs, which used to subscribe to commercial papers (CPs) and bonds of NBFCs and other corporates, started pulling out. Covid-19 added fuel to this fire as industries across sectors, particularly aviation, tourism, hospitality and transportation, were hit hard. "Private banks are answerable to shareholders. They will not lend when the environment is not good," says a fixed income dealer.

Last week, banks deposited a record Rs 8.50 lakh crore surplus under the reverse repo window, the highest in recent history.

Government, The Guarantor

As things stand today, no amount of liquidity injection by the RBI can solve the risk-aversion problem. "It requires intervention from the government," says Chari of Quantum.

Banks with funding exposure to NBFCs, MSMEs, MFIs, etc, do not want to take further credit exposure without loss protection guarantee from the government or the RBI. Some banks are offering additional working capital to Covid-impacted sectors, but the number is very limited. Banks also have their own risk assessments. Why will they do something that is not commercially viable?

A government guarantee will, therefore, soothe frayed nerves, according to experts. The Centre can rope in SIDBI and other institutions to offer such a guarantee. "The government can do the first-loss guarantee where loan losses would be first compensated by the government," says Ashish Shanker, Head of Investments at Motilal Oswal Private Wealth Management. The first-loss guarantee can be a minimum percentage of the loss or the full first loss. In fact, post the IL&FS debacle, the government had offered a 10 per cent first-loss guarantee to PSBs (Rs 10,000 crore) to buy high-rated pool assets (home loans and micro loans) from financially sound NBFCs up to Rs 1 lakh crore.

The SPV Model

Experts suggest creation of a special purpose vehicle (SPV) for Covid-hit sectors. The government and the RBI can put in the initial capital whereas banks, LIC and other large institution can contribute the rest. The fund size could be around Rs 1 lakh crore. "Private equity players can also be roped in. There are also options like tax-free bonds for retail investors to mobilise funds," suggests Murthy Nagarajan, Head (Fixed Income), Tata Mutual Fund.

"The government-guarantee model will work for small enterprises, which do not have the ability to issue capital instruments such as non-convertible debentures (NCDs). But the SPV model is ideal for buying paper from NBFCs or other mid-size companies," says Ashutosh Khajuria, Executive Director, Federal Bank.

"The moratorium of a quarter won't solve the problem. There has to be a fund which can support the industry for one or two years," says Shanker of Motilal Oswal.

Last year, the government had come up with a Rs 25,000-crore Alternative Investment Fund (AIF) for the battered real estate sector. The government acted as the sponsor with Rs 10,000 crore initial capital, while SBI and LIC contributed the balance Rs 15,000 crore. SBI Capital was the fund manager. In 2008, after the global financial crisis, the government had come out with an SPV model to provide liquidity support to NBFCs. The RBI agreed to purchase securities issued by the SPV and guaranteed by the government up to Rs 20,000 crore. The SPV bought high-rated short-term CPs and NCDs from NBFCs, creating liquidity.

Recapitalisation of PSBs

The government can also provide PSBs capital to help sectors worst hit by the virus outbreak. It had earlier come up with the Mudra loan scheme where banks provided collateral-free loans of up to Rs 10 lakh.

Bank of America Securities has recommended the bond model to recapitalise banks. Under this, the government issues bonds, which are subscribed by banks. The money collected by the government comes back to banks as capital. Banks earn interest on bonds, which is actually the net inflow from the government. According to Bank of America Securities, there is a need for recapitalisation worth $7- 15 billion (Rs 52,600-1,12,500 crore).

"We shouldn't paint all NBFCs with the same brush. There are NBFCs with high capital but they may face asset liability issues because of a one-sided moratorium," says Shanker of Motilal Oswal.

RBI's Revaluation Reserves

According to Bank of America Securities, the RBI is sitting on Rs 9.6 lakh crore revaluation reserves, which can be used to recapitalise banks. These reserves arise from revaluation of assets that are undervalued on the books. However, tapping these will be a difficult exercise. Though the Bimal Jalan Committee had recommended setting minimum capital levels and transferring excess surplus to the government last year, transfer of such reserves is not permitted under RBI rules. "There are significant strategic and operational constraints in monetisation of revaluation balances," the Jalan committee itself had noted.

Also, the reserves represent the valuation gains on foreign exchange because of appreciation of the dollar against the rupee. Any sale of forex assets to book gains will result in a fall in foreign exchange reserves, which are currently equal to 10-11 months of imports. Given the high volatility in the rupee's value against the US dollar post-Covid, this may not be the right time to explore this option.

Tapping Global Funds

Many NBFCs, MFIs and Fintechs, which were earlier solvent, are likely to fall short of funds post-Covid due to losses on the asset side. "The asset side problem won't be solved by debt," says Shanker of Motilal Oswal. To aid cash-strapped infrastructure companies, the Centre recently gave 100 per cent tax exemptions to sovereign wealth funds to invest in the sector. The government could look at tapping such funds.

MSME Minister Nitin Gadkari recently suggested a Rs 10,000-crore Fund of Funds (a pooled fund that invests in other funds) for the sector. Under the proposal, MSMEs would tap the capital market and the fund would buy 15 per cent equity. There are also suggestions like strengthening the bill discounting model. "The government should work with large scale and mid-size companies for facilitating bill discounting (advance against bills) and factoring (purchase of debt by banks)," says Singh of Dun & Bradstreet.

Expanding the HTM Bucket

Banks currently keep government securities and bonds under three categories -- Available for Sale (AFS), Held for Trading (HFT) and Held to Maturity (HTM). Going forward, banks can be encouraged to invest in government securities (G-Secs), state bonds and corporate bonds to address the problem of surplus liquidity. AFS and HFT attract mark to market losses for any rise in yields and fall in market prices (they have to be liquidated within a shorter time period). Since in a post-Covid world, the chances of such losses are high because of fiscal stimulus and higher market borrowings resulting in higher yields and falling bond prices, banks prefer the HTM route (securities and bonds can be owned for a longer period). "A rise in the HTM bucket could create an appetite for government bonds because you are not allocating risk capital," says Choudhary of IDFC AMC.

However, Murthy of Tata Mutual funds says compared to PSBs, private banks don't have excess statutory liquidity ratio (SLR), which offers the scope for buying securities if the HTM window is hiked from the current 25 per cent. SLR is the amount banks have to maintain in the form of cash, gold or securities.

Lender of Last Resort

The RBI has assured that it will not allow any NBFC to fail. But lenders are wary that a post-IL&FS situation, where no one came to their rescue, could surface once again. There are demands for a direct funding line from the RBI, which doesn't seem to be a possibility for now. The RBI could, however, support government-backed NBFCs since there is a sovereign guarantee.

"Most of RBI's efforts have been to ensure that the bond market does not go out of control," says Chari of Quantum. The government plans to increase borrowing by Rs 4.2 lakh crore to a massive Rs 12 lakh crore in 2020/21 is likely to push up the yields or interest cost. There could be rating action by global rating agencies. "The next wave of liquidity mismatches and defaults will happen soon if impacted sectors like MSMEs are not supported. MSMEs have fixed expenses to pay. There is lack of demand. The pressure from vendors for payments will soon increase," says Singh of Dun & Bradstreet.

So, at the moment, it's up to the government to come up with a stimulus package.

@anandadhikari