In an industry that is barely 12 years old in the country, the second generation of microfinance entrepreneurs has already burst onto the scene. What’s different about Microfinance Entrepreneurs Ver 2.0? Most of them are either MBAs or have given up lucrative corporate jobs; unlike the previous generation of microfinance institutions (MFIs), which typically started as non-governmental organisations (NGOs) without any proper structure or business model, the newer lot is registered either as non-banking finance companies (NBFCs) or Section 25 companies, which essentially is a non-profit structure in a corporate form. Also, none of them is looking at microfinance as teary-eyed charity. Sure, they love working with the poor, but what they offer is financial services for the poor and, often, are funded not by grants but professional investors. Accordingly, they are leveraging technology, hiring professionals, improvising on existing MFI models, and looking beyond the traditional microfinance bastion— and, indeed, pure microfinance itself—of south India. Says S. Viswanatha Prasad, whose two-year-old fund, the Bellwether Microfinance Fund, is the first of its kind: “We want to help build the next generation of MFIs by expanding the (microfinance) pie.” Adds Sitaram Rao, an industry expert: “They are all fiercely independent and some of them are using their lives’ savings to start microfinance in remote regions.” So, just who are these new kids on the MFI block? One of them was a principal architect of Vikram Akula’s SKS Microfinance, another is the son of a former Chief Minister, two others helped build Cashpor, a UP-based MFI, yet another worked with a leading financial institution before diving into microfinance, while the other three boast of equally impressive track records. Take a look:

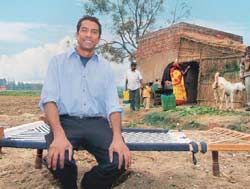

Rural market maker

Harsha Moily uses microfinance to create a rural market place.

Harsha Moily, 36

Year of Founding: 2005

Focus: Microfinance and related areas such as insurance

Current Size: 27,000 customers for micro-credit

Current Equity: Rs 1.45 crore

Funding Plans: Rs 8 crore from a US-based VC and high networth individual

— Rahul Sachitanand

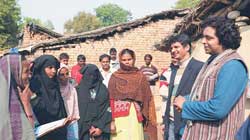

Banker of the GT road

Manab Chakraborty’s Mimo Finance lends to the poor of Uttarakhand.

Manab Chakraborty, 52

Year of Founding: 2006

Focus: Microfinance for women in urban and peri-urban areas

Disbursals: Rs 5.76 crore

Plans: 4 lakh clients by 2011

Current Equity: Rs 1.19 crore

Funding Plans: Looking at long-term investors

Uttarakhand needs help. Chakraborty says more than 35 per cent of the state’s population of about 85 lakh people live below the poverty line. “We want to expand along the GT Road because the poor in urban and urbanising areas need financial services as much as the rural poor,” says Chakraborty. His ambition is to reach 4 lakh customers in three years and a million by 2015—mostly in northern India. “Microfinance is very satisfying. You help others and you help yourself,” says the man who owns 30 per cent of the MFI.

— Kapil Bajaj

Urban innovator

Kolkata-based Arohan is tapping the urban poor.

Subhankar Sengupta, 34

Year of Founding: 2006

Focus: Urban poor in eastern India

Disbursals: Rs 16 crore

Plans: To reach 250,000 clients with a loan portfolio of Rs 100 crore+

Current Equity: About Rs 2 crore

Funding Plans: Looking at equity infusion from institutional sources, and borrowings from banks

Sengupta has taken the advice to heart. While the rural poor are undoubtedly a bigger market for MFIs, the 34-year-old’s Arohan has chosen to focus on the urban poor. For good reason. Remarkably, 25 per cent of West Bengal’s population is estimated to live in Greater Kolkata—that is within 50 km radius in the districts of North & South 24 Parganas, Howrah, Hoogly & Nadia—creating one of the world's largest human habitats (nearly 25 million). Arohan’s urban clients range from microentrepreneurs to small and marginal farmers to wage labourers. So far, the MFI, which has been funded by Mahajan’s flagship firm Bhartiya Samruddhi Finance and angel investor-cum-journalist Swaminathan S. Anklesaria Aiyar, has a customer base of 23,000 with a cumulative loan disbursement of Rs 16 crore (loans typically range from Rs 5,000 and Rs 10,000 each). What’s next for Arohan? “It’s time to scale up—from raising the loan limits to bringing in more innovative products to expand geographical coverage area,” says Sengupta.

— Ritwik Mukherjee

Comrades in arms

Two friends and a common mission.

Rakesh Dubey, 36 & Anup Kumar Singh, 36

Year of Founding: 2006

Focus: Families below poverty line

Disbursals: Rs 35 crore

Plans: Lend Rs 1,000 crore by 2013

Current Equity: Rs 1.97 crore

Funding Plans: Talking to Sidbi and other investors to raise Rs 16 crore in additional equity by 2012

Thanks to their long experience in the industry (the duo has trained at Grameen Bank in Bangladesh, besides Nepal and south India), Singh and Dubey have come up with a hybrid model for their MFI that uses both agents and the selfhelp group (SHG) concept. Here’s how: The agents are used to help get groups of customers, and the groups themselves are allowed to be larger than Grameen Bank’s limit of five and closer to SHG’s size of 10. “The idea is to give greater flexibility and reduce costs,” says Singh. Sonata has over 30,000 clients and a total outstanding of Rs 16.2 crore—a growth of over 300 per cent in one year. In August 2007, Sonata even acquired another MFI to get a toehold in Madhya Pradesh.

— E. Kumar Sharma

Universal lender

Kishore Kumar Puli is looking beyond micro-credit, and the poor.

Kishore Kumar Puli, 36

Year of Founding: July 2007

Focus: The poor in rural and periurban areas, and also educational institutions in villages

Disbursals: Rs 3.5 crore

Plans: Disburse Rs 300 crore by 2013

Current Equity: Rs 2 crore

Funding Plans: Have an equity base of Rs 10 crore by 2013; also tap banks and other partners for debt

What makes Annapurna different from other MFIs, the MBA from Hyderabad’s Osmania University, says, is that it is looking at both poor and near-poor clients (for example, personal loans for Class IV government employees), and also rural educational institutions. “The bottom line is we intend to offer as many products as possible to serve the needs of varied segments of the clientele,” says Puli, who’s also done a longish stint at Vijay Mahajan’s BASIX.

Like some of the other MFIs featured in this story, Annapurna is leveraging IT to lower costs and improve delivery and service. Puli’s goal is to halve transaction costs to 7-8 per cent and grow from four branches to 70 over the next five years. “We want to reach out to the untapped and under-served regions and hit total disbursals of Rs 300 crore in that time,” says the laptop-toting Puli. No wonder, he is a man in a hurry.

— E. Kumar Sharma

Delivering hope

Praseeda Kunam serves one of India’s poorest districts, Rewa.

Praseeda Kunam, 33

Year of Founding: October 2007

Focus: Rural poor women

Disbursals: Rs 3.7 lakh

Current Equity: Rs 8 lakh

Funding Plans: Is in talks with Opportunity International, Australia , and Michael and Susan Dell Foundation

Rustling up Rs 8 lakh, Kunam set up Samhita Community Development Services as a Section 25 company. “Our entire approach is geared towards establishing the microfinance distribution channel and using it to deliver various non-financial services that are so desperately needed by the poor,” says Kunam. Courtesy her husband, Balachander Krishna Murthy (an IIT and University of Chicago alumnus), Kunam plans to leverage IT to track her customer’s performance on social, economic and health fronts. “The possibilities are endless, but we will take one step at a time,” says Kunam, who picked Rewa because the region ranks low on most development indices.

— E. Kumar Sharma

Speedy money

4,500 customers within a month of launch? This man has done it.

P.N. Vasudevan, 45

Year of Founding: December 2007

Focus: Microfinance and other products

Disbursals: Rs 5.5 crore

Plans: Reach 150,000 customers in the first year alone

Current Equity: Rs 7.5 crore

Funding Plans: Looking for PE funding

Smart use of IT is what drives UPDB’s spectacular performance. It has introduced a centralised processing system at the corporate office so that the various branch offices can focus on selling and send the documents to the head office by courier. A web-enabled software in turn hooks up all the 9 branches with the centralised database, giving the branch managers access to application status, customer payment details etc on a real-time basis. This has resulted in lower overheads at branches and, ultimately, lower cost to customers. “We offer loans at 25 per cent with a rebate of 2.5 per cent for prompt payments because I don’t want to pass on high costs of overheads to customers,” he says. No wonder the customers are queuing up. Vasudevan’s next brain wave: ESOPs for the field force, which typically comprises high school graduates. “It is to make them understand that they would participate in the profit,” says Vasudevan. This is one gesture his team wouldn’t have too much trouble understanding or appreciating.

— Nitya Varadarajan