Look around you. In your pockets, your home, your office. On your way to office or a vacation. Look at how you communicate with colleagues or loved ones. How you cook. How you wash clothes. And shop. Or pay your bills. In fact, look at everything you do when awake. What’s common? It’s something that’s hidden, inanimate, seemingly innocuous, but omnipresent. And it just stopped the world.

“A single semiconductor chip has as many transistors as all of the stones in the Great Pyramid in Giza. And today there are more than 100 billion integrated circuits in daily use around the world—that’s equal to the number of stars in our corner of the Milky Way galaxy,” the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA), a US trade group, says on its website.

Yet there aren’t enough chips in the world to meet the skyrocketing demand. Global chip sales hit $48.8 billion in October 2021, a 1.1 per cent increase over September and a 24 per cent jump from October 2020, as per the SIA. And why not? Semiconductors, after all, are the brain of every electronic device. For instance, without a chip to control the motor’s speed, an electric toothbrush would be, well, just an ordinary toothbrush. A car houses anywhere between a few hundreds and thousands of chips that handle everything, from the basics of keyless entry to the complex engine control unit (ECU). And one can only imagine the number of chips in high-end defence systems or spacecraft.

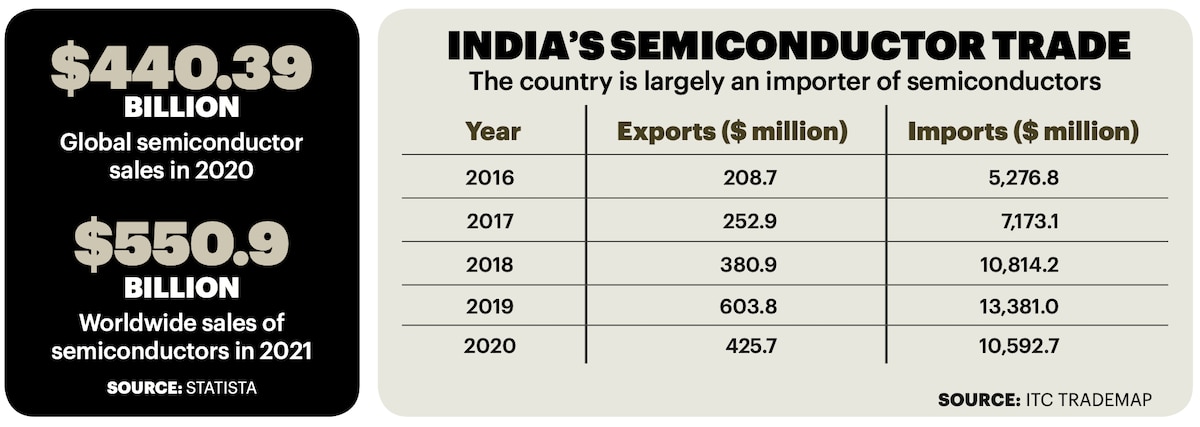

When Covid-19 forced the world to lock down last year, the chip ensured we did not hit a standstill. Smartphones kept us connected, data servers kept the information flowing, laptops and computers let us work or study from home, while automation meant parts of the global supply chain still creaked on. But that created new problems. “The digitisation of everything has led to unprecedented demand for semiconductors. This has led to an industry-wide shortage of critical third-party components that are needed for chip manufacturing. In addition, the manufacturing process for chips is complex, multi-tiered and usually multinational, leading to difficulties in transporting materials across borders during the pandemic,” says Nivruti Rai, Country Head, Intel India, and VP, Intel Foundry Services.

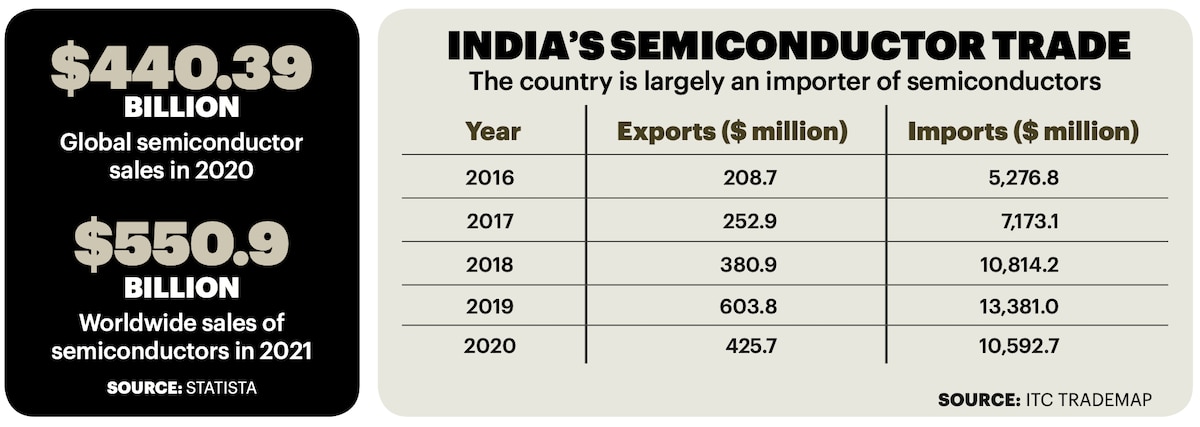

The chip industry is as global and complex as the chip itself is. The industry that was worth about $440 billion in 2020, as per research firm Statista, is estimated to grow to about $550 billion this year, on its way to crossing $600 billion next year. It is an industry that made countries realise it was more fruitful to be an integral part of the ecosystem than being its customer. Among those countries is India.

The country has a strong foothold in the designing leg of the ecosystem, with companies such as Intel, Micron and Samsung (Semiconductors) housing some of their R&D centres in India. However, India has no skin in chip manufacturing and relies solely on imports. “Roughly, India imports $10 billion worth of semiconductors. About 40 per cent of our imports originate from China, and 26 per cent from Hong Kong,” says Prahalathan Iyer, Chief General Manager, Research and Analysis, India Exim Bank.

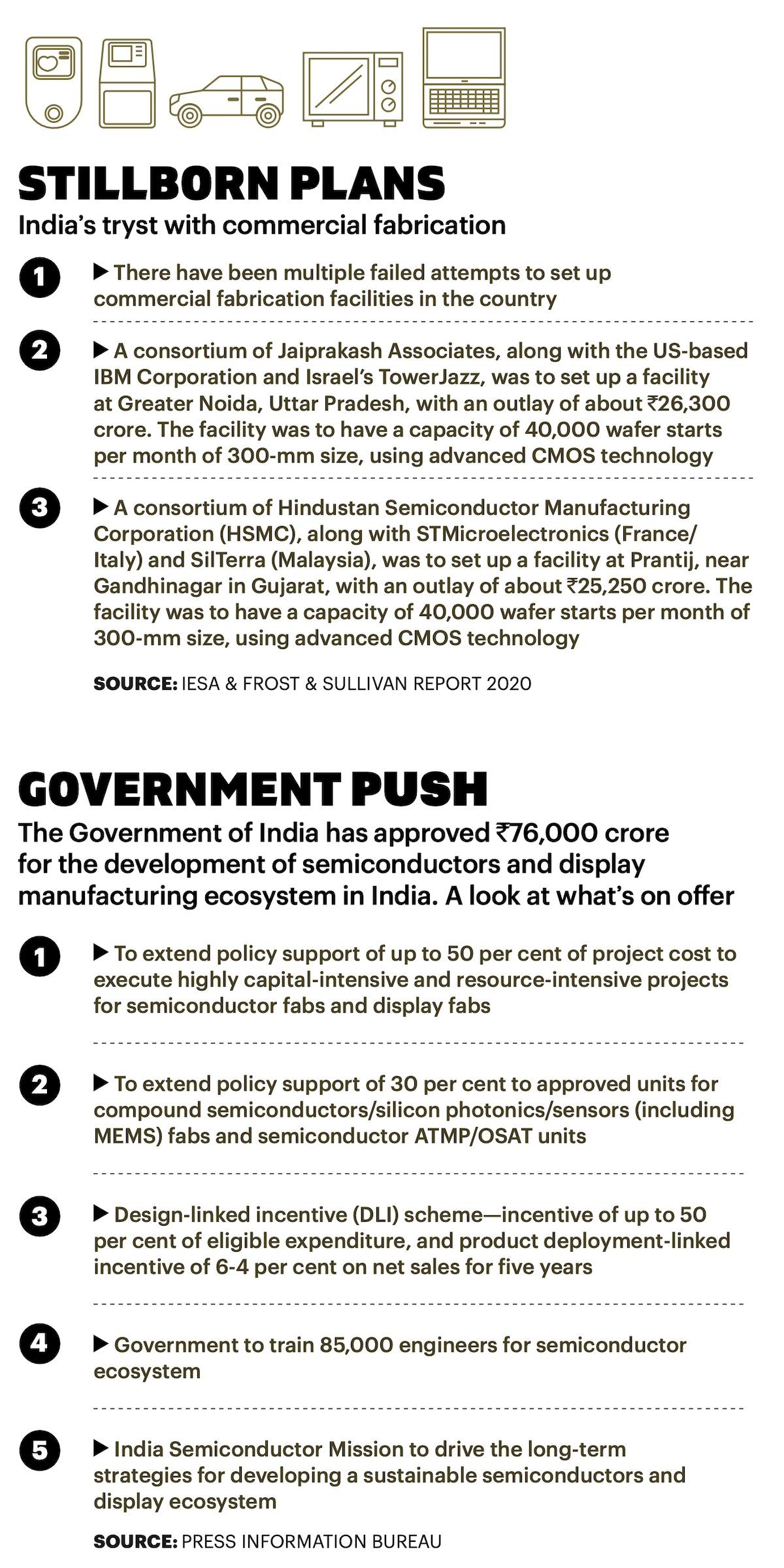

It’s this gaping hole that the government is trying to fill with a scheme to promote domestic manufacturing. The focus is not just on making chips, but also its components, so that it benefits the entire domestic electronics manufacturing industry. “The PM’s vision and support for this has been steadfast and the recent `76,000-crore package will transform and leapfrog India’s electronics and semiconductor industry, and will catalyse investments, entrepreneurship and jobs,” explains Rajeev Chandrasekhar, Union Minister of State for Electronics and Information Technology, as well as for Skill Development and Entrepreneurship (read full interview on Page 37). This, he adds, will make India’s domestic electronics manufacturing a $300-billion industry by 2025-26 from a $75-billion market in 2020.

The Global Trail

The chip industry’s headliners are the likes of Intel, Micron, Nvidia, AMD and Qualcomm, whose chips power devices such as smartphones, laptops and gaming devices. That, though, is the front-facing layer of the ecosystem.

Firms such as Intel, Samsung and Micron are known as IDMs, or integrated device manufacturers, as they both design and, for the most part, manufacture chips. On the other hand, the likes of Nvidia, Qualcomm, AMD and Taiwan-based MediaTek only design chips. These so-called fabless companies outsource the production to contract manufacturers. The top pure-play manufacturers, or foundries, include Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), China’s Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC) and GlobalFoundries.

These manufacturers first turn silicon powder into wafers. Then dozens of transistors are printed onto these wafers and connected by copper wires to convert them into memory chips, microprocessors, or the complex systems-on-a-chip (SoCs). These processes could involve anywhere between 300 and 700 steps. The machines that handle these processes are made by companies such as Netherlands-based ASML, Japan’s Tokyo Electron and US-based Applied Materials. Once printed, the chips are shipped to testing and packing facilities such as those of Amkor Technology in the Philippines and Unisem Group in Malaysia. When ready, the chips are shipped back to the designers. In a nutshell, chipmaking is a time-consuming task. “It depends on the complexity of the chips. From conceptualising to actual production, it can take anything between 15 and 18 months. For other less complex chips, it takes around 8-12 months for the final resulting product,” says Balajee Sowrirajan, MD, Samsung Semiconductors India (SSIR).

However, the industry’s complexity runs beyond a globally diversified ecosystem to include a web of rivalries and cooperation between companies. For instance, as an IDM, Intel is both a designer and foundry, meaning it could be producing chips for rivals. Despite that, it is planning to shift more production of its high-end chips to TSMC. Its rivals such as Qualcomm and AMD also use TSMC, as does Apple, its biggest customer.

Of course, the underlying strain is that each company is looking to diversify its supply chain. The need for that has become more pronounced during the past couple of years. For example, Apple said supply chain issues cost it $6 billion in sales in the September quarter and could have a bigger impact in the last quarter of the year.

No More Chips

Interestingly, Apple CEO Tim Cook said the shortage was for legacy nodes, which use older manufacturing methods, rather than the modern, high-performance chips that power its gadgets. This harks back to the start of the pandemic.

In early 2020, when nations were imposing lockdowns, automakers realised car sales would be hit and reduced orders for chips. On the other hand, given the ballooning demand for smartphones, computers and other consumer electronics, foundries like TSMC recast their spare production capacity. However, it’s not as if chips for consumer devices were readily available. Lockdowns meant component factories, testing and packaging facilities, and other parts of the supply chain were also disrupted. There were natural disasters as well. A winter storm in February forced NXP Semiconductors and Samsung to close their plants in Texas. Then, a fire forced Renesas Electronics (whose chips are used by the likes of Toyota, Nissan and Honda) to shut its Japan plant.

There is also the Sino-US economic war, which intensified after Washington imposed restrictions on SMIC. This made it hard for the China-based foundry to supply to US-based clients, forcing them to turn to the likes of TSMC and Samsung. However, hardly any foundry had spare capacity given the consumer electronics boom. By this time, the demand for cars had rebounded, leaving automakers scrambling. This chain of events was exacerbated until the world ran short of chips. In all, Goldman Sachs estimates the shortage affected over 169 industries globally, with the automobile industry hit the hardest. As it was in India.

“The shortage of semiconductors to Tier I and Tier II suppliers of OEMs has affected supplies of engine ECUs, keyless entry, ABS systems, infotainment systems, etc.,” says Rajesh Menon, Director General, Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers (SIAM). The electronics industry was also not immune. Chip shortage has pushed back Super Plastronics’s lead time for smart TVs from 30 to 120 days, says CEO Avneet Singh Marwah.

And it’s not as if foundries can scale up manufacturing overnight to match demand. “The biggest challenge in increasing production capacity is the huge investment, especially when making new clean rooms. Other issues include long lead times to install manufacturing equipment, securing skilled operators, and sufficient water and power,” explains Takao Yagi, General Manager, Semiconductor Sales and Marketing Center, Toshiba Electronic Devices and Storage Corporation. It can take as many as three-four years for a new facility to start commercial production.

Foundries, though, have started the expansion process. For instance, TSMC has partnered with Sony to invest $7 billion to build a plant in Japan. It is also building a new foundry in the US, as are Intel, Texas Instruments and Samsung. Automakers are also locking down contracts. For instance, Ford has tied up with GlobalFoundries, while BMW has partnered with Qualcomm to provide chips for its upcoming range of electric cars.

Not just companies, countries have also laid out plans. The US Senate approved $52 billion for CHIPS for America Act earlier this year, while India has approved `76,000 crore for development of the semiconductor and display manufacturing ecosystem.

Make in India

“A country that is now aspiring to be an electronics hub in the electronics global value chain, which is India, is also now faced with a growing global concern about the concentration of semiconductors in certain geographies, that may or may not be resilient over the medium term or long term,” says Union Minister Chandrasekhar. “And therefore, there is an added reason and rationale for India to explore the semiconductor opportunity in the context of electronics opportunity growth and semiconductor sovereignty, security, as well as product categories like EV.”

India’s role in the global chip ecosystem has been limited to chip design. “India is a semiconductor design powerhouse due to its excellent engineering talent,” says K. Krishna Moorthy, CEO and President, India Electronics & Semiconductor Association (IESA). While setting up a design centre requires millions of dollars, “the return on investment in terms of the design work is very good”, he says.

But India’s ambitions lie further down the ecosystem—to be a part of the manufacturing process. For that, it first needs to sow the seeds of a longer-term vision to attract investors. “You do not get billions of dollars if you do not give the investors long-term policy views. And also, we can start building the surrounding ecosystem of metals, chemicals, minerals used in semiconductor manufacturing first, as well as set up assembly, testing, marking, and packaging (ATMP) facilities, and develop them to a maturity level in two-three years,” says Moorthy. “These will act as a pull factor for fab houses.”

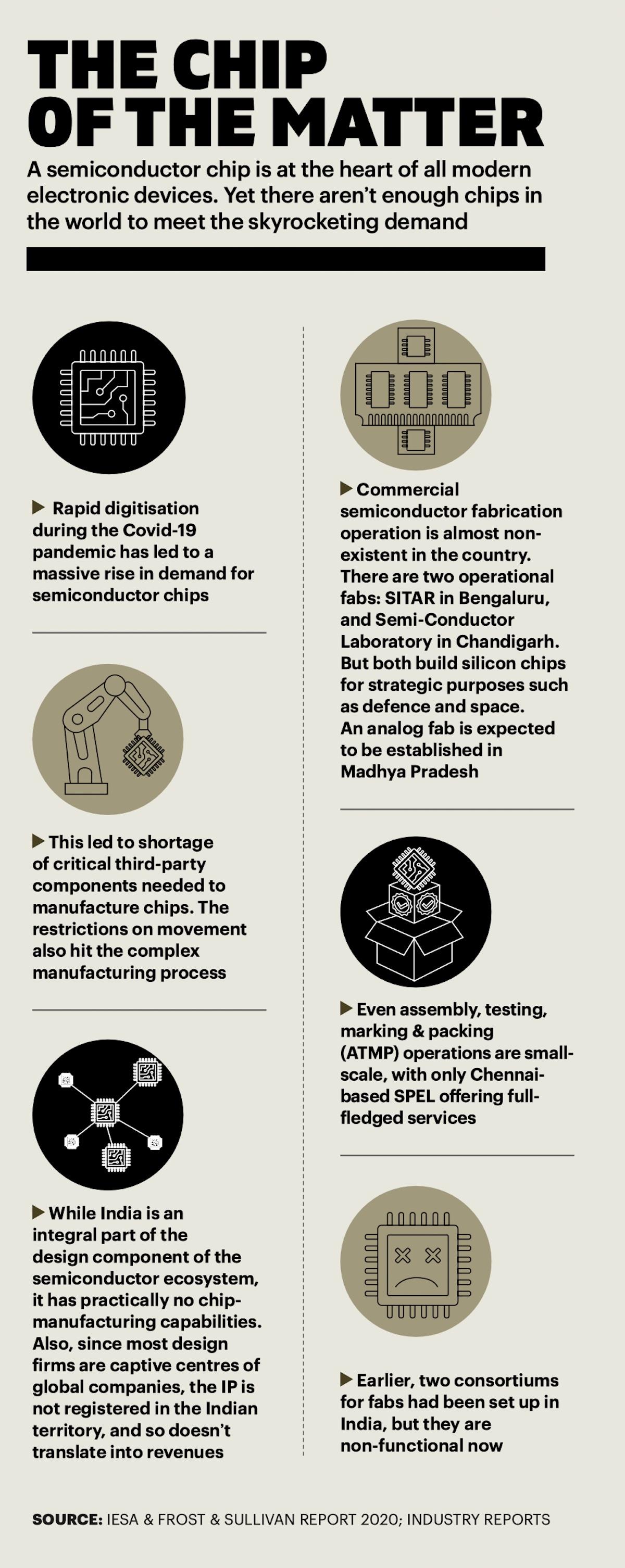

India has two operational fabs. But their chips are for strategic sectors such as defence and space. Among the country’s fabless companies is Bengaluru-based Saankhya Labs, which focusses on communication chips, including for 4G and 5G communication. But like many of its global peers, Saankhya uses chips made by TSMC and Samsung. It is this outsourcing that India wants to bring in-house. That could become a reality in the next five years with the programme for development of semiconductors and display manufacturing ecosystem in India.

The scheme is designed to strengthen the entire electronics manufacturing ecosystem in the country. Along with offering policy support of 50 per cent of project cost on a pari-passu basis to eligible applicants with technology and capacity to execute highly capital-intensive and resource-intensive projects, the government will offer support of 30 per cent of capital expenditure for setting up compound semiconductors and ATMP, etc. To strengthen the fabless ecosystem, an incentive of 50 per cent of eligible expenditure and product deployment-linked incentive of 6-4 per cent on net sales for five years will be offered under Design-Linked Incentive. Plus, 85,000 engineers will be trained to work in the semiconductor ecosystem.

Fabless companies are welcoming the government’s ecosystem-led approach. As Parag Naik, Co-founder and CEO of Saankhya Labs, explains, “If you want to be a truly developed country, develop technology to increase the GDP. You have to be a powerhouse in electronics. And to have one big Intel, there have to be 150 or 200 smaller mini Intels in the country.”

As India goes about achieving its ambitions, industry players have some words of advice. And caution.

For one, India should begin its manufacturing journey starting with the widely used legacy nodes and not advanced ones, says Anand Ramamoorthy, MD, Micron Technology (India). “Like in most industries, if you just start with advanced nodes, by default the yield and the economies of scale will not set in until a few years down the line. And since we’re coming from behind, it makes more sense to look at the current supply chain shortages. Because we are finding that much of the shortfall in automotive markets is not of leading-edge, but lagging-edge products.”

Neeraj Bansal, Partner, Risk Advisory and COO, India Global, KPMG in India, says a deciding factor for location of semiconductor manufacturing facilities is proximity to companies that are the end users of semiconductor components. “In India, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh are leading manufacturing hubs for automobile, mobile phones and industrial parts, and setting up semiconductor manufacturing facilities adjacent to these end consumers would be advantageous to both,” Bansal explains.

But the industry should be cautious as the chip shortage now could become a case of oversupply in a matter of months with beefed-up production. “The industry has witnessed several ups and downs over the past five years. The momentum witnessed in 2016 was eclipsed by challenges like rapid technological changes, the adoption of new technologies and consolidation in the space,” says Anku Jain, MD, MediaTek India.

After all, it took about 2.3 million stones to build the Great Pyramid of Giza.

@nidhisingal