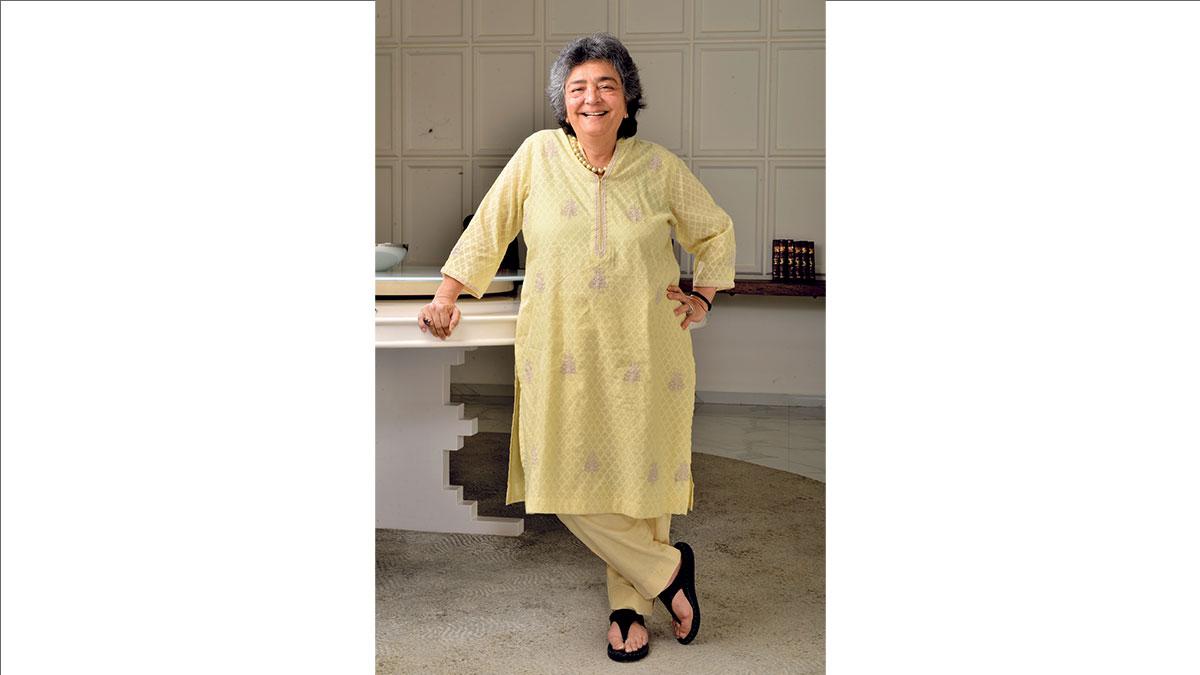

She is one of India’s top corporate lawyers and the go-to person when some big deal or restructuring is planned. From the acquisition of Jaguar Land Rover by the Tatas, the L&T-Mindtree deal, the Cairn-Vedanta deal, SoftBank buying a stake in Ola or, more recently, the HDFC-HDFC Bank merger, Zia Mody, Co-founder and Managing Partner of AZB & Partners, has had a role to play in all of them. In an interview with Business Today’s Global Business Editor Udayan Mukherjee, she reveals what attracted her to the legal field, her inspiration, and the business leader she looks up to. Edited excerpts:

Q: Zia, let me begin by asking you if it is an exciting time to be a lawyer in India today, because there’s so much going on—in the M&A landscape, with foreign direct investment pouring in, and even the much spoken about judicial activism in the public sphere. It must be exciting.

A: Look at my face, Udayan! Isn’t it looking excited? I think it is one of the most fascinating periods for any young lawyer to be part of the entire development of corporate M&A, and of legal jurisprudence—either arguing in court or being a young corporate attorney sitting in on a mega M&A deal. The world has changed from about 20 years ago, where law was not necessarily the first calling of choice. But now, becoming a lawyer and hoping to aspire and reach the top of your game is very much a possibility and a dream that many youngsters want to dream. And therefore, we are seeing many more talented youngsters join the legal profession than we saw before. So, the simple answer to your question is a big yes.

Q: Actually, I don’t remember the profession being such a major part and parcel of public discourse as it is today; all this talk about the judiciary actually being an offset to the executive. Do you agree with the resulting allegations of judicial overreach, or do you support the view that the judiciary needs to become part of public life as it seems to have become in our country today?

A: There are times when there are troughs and peaks of what you call judicial activism. Personally, I welcome judicial activism. Yes, sometimes it can be overreaching, when you end up calling the government back on weekends and ask them to give you a school report. But other than that, it is what keeps all three branches [of a democracy] in check, reminding each that they are ultimately accountable for their behaviour. It is clear to me there are some things that would never have happened without judicial intervention. You take the writ of habeas corpus, the matter of undertrials being kept in prison, the situation in orphanages, so many public interest litigations which have led to change in legislation, better government behaviour, and a sense of wariness that if you overstep the moral line, the Supreme Court is there to haul you up and ask you to be accountable.

Q: You have worked with so many CEOs and managements over the years. Would you say Indian promoters innately respect the law or are they always trying to work around it, bend it, or tweak it in some way?

A: As always, there’s no one easy answer. There are CEOs today who, over the last 10 years, have changed and recognised that trying to skirt the law or be over cute, or go too close to the edge, is not productive because when the regulator comes after you, then you have to answer for all that cuteness. So, many CEOs today come and ask me—what is the right course of conduct, which is the least risky, maybe just a little risky, but they no longer ask for the outright risky path; they just don’t want to know that. So, the risk appetite, if you like, has reduced, which is a change in the DNA of the culture of the Indian firm. These are larger firms that go to market, often with a lot of foreign direct investment in them, and a reputation which needs to be protected. And so I see this change for sure in these CEOs.

Then there are, of course, smaller companies where you have a mix. There are some that still have a high risk appetite and are willing to face regulatory intervention. And there are some which may yet be small, but know that private equity (PE) will come for them, and they will come at a premium only if your track [record] is good.

Q: I want to get back to the start of your story, Zia. As a young woman, were you always going to be a lawyer, having been born into such an illustrious legal fold, or was there something intrinsically or philosophically attractive about law as a profession, which drew you in?

A: No, I don’t think at the age of 20-25, I would have been attracted by the philosophy of law. As a young girl, it was very exciting to see my father practising as a lawyer. And he was in court every day, but the whole family would have dinner together. And then you would hear all these conversations—one side of the conversation anyway—through a walkie-talkie phone that existed in those days. It was always frenetic, energetic, argumentative, you know; having to win every time, fighting everything as a war, never a skirmish. And, given that I also have quite an argumentative nature, it appealed immediately.

For me it was almost like osmosis. I don’t remember ever wanting to do anything but the law.

Q: It must have been heartbreaking to lose your father to Covid-19 last year. What are your key learnings from Soli Sorabjee, the jurist? Just inspiration as a young woman, or are many of the things in your guidebook drawn from what he taught you?

A: I think the value system, which he asked me to follow from the first day. I worked in America for nearly five years at a firm called Baker & McKenzie, New York, and came back essentially to get married and step into another world altogether. My desk was a small, 4 ft by 5 ft desk which I shared with my senior, and we had no secretary. It was sweaty and packed and full of papers. And, it was really starting from scratch. It was arguing in court as opposed to an M&A transaction that I would be working on in New York. My father was in Delhi, I was in Bombay. So, we never really got to practise in the same city. But he would always tell me—don’t forget that the ultimate person you are arguing before is a judge, and that you are always an officer of the court; that your client is important, but never more important than your reputation with the judge. And he always used to tell me that if you say one thing wrong in one matter, before one judge, you have had it. They all have lunch together, and you would have ruined your reputation over one lunch. When you are brought up on this advice, you always have to do the right thing. That doesn’t mean you can’t fight heart and soul for your client. But there’s a limit beyond which you need not travel. And, ought not to travel. Your sense of self-worth and confidence, and your ability to sleep at night without vexing about what you did during the day is far more important than winning that fight with the wrong means. So I’ve always grown up to acknowledge clients as important, but not vitally necessary to my existence if they cross my moral compass.

And with those values, the clients in turn respect you because they understand that the moral compass you deliver to them is for their benefit. I am not getting anything out of their good behaviour, I’m just protecting them. And slowly and surely as you grow older, and fatter and wiser, people take you a little more seriously. So that was one of my father’s greatest lessons to me and counsel to me. Just make sure whatever you do, you’re able to deliver the advice in a manner that you don’t regret delivering the next day.

Q: And what he may or may not have told you was that all these judges who had lunch together, were mostly men. There could be no doubt that you were entering a male bastion. What was it like? Would you tell a young woman who is considering law as a profession today that things are vastly different than when you got into this profession?

A: So it’s in two buckets, Udayan. Today, if you’re a practising counsellor or a barrister, as a woman, even after so many decades, I will say it is still extremely tough. I’m not sure I can put my finger on it, other than to say that it’s a difficult world to break into. And, as a woman, it absolutely requires extra time and commitment to show that you are as good as your peer who is a male.

I remember when I was a young barrister, I would always work 30 per cent more than my male counterpart because I was capital P for paranoia. I couldn’t afford to make a single mistake in court, because I was so conscious that I was probably the only woman who was arguing that matter on that day. So as arguing counsel, still not good at all. I think we have a long way to go. It is very hard to be dancing and prancing and acting day after day for eight hours, preparing for another five hours at night for the next day, and having to multitask as a woman without the essential social infrastructure and ecosystem.

As a corporate lawyer or as a non-litigating lawyer, it has become much easier for women. Not terribly easy, but much easier. And that is simply because in today’s world, everybody needs talent. And if they need talent, then women are talent. So, you can’t afford to just let any bright woman drop off the landscape and fade away from the firm without making that effort to retain that incredible source of talent. So, it is getting better for sure on that front.

Q: You’ve been at the forefront of many of these recent PE deals like the SoftBank-Ola deal, which have created such a large number of unicorns. What do you make of this trend? I was speaking to your friend Ronnie Screwvala, who said PE can become an end in itself. Would you sound a word of caution as well, given the kind of valuations that are being drummed up by PE infusion in India today?

A: You can’t have it both ways, right? You can’t say I want these incredible valuations but not welcome the person who is going to give them to you. So, it is the mix between where the promoter wants to draw his or her own line, and the PE investor that is willing to bet on you. For the young unicorns, the PE [investor] is betting on individuals who will have the energy to turn the value that they give into even higher values. And in today’s world, India is getting a very nice share of the wallet from the world of private equity.

You take a promoter like Ronnie, who has been successful time and again, and he has basically been able to create these incredibly valuable institutions and companies, so people are betting on him and the young people that he’s working with. If they provide the value, then they expect an exit, for that’s the rule of the game—if you want a value which is great, give me an exit that is greater.

And so that cycle and that merry-go-round goes on but I think that PE is immensely important and valuable to the country because it has allowed the world to recognise our companies. And it has put a value on our companies that didn’t exist 10 years ago. So, today when you see our mid-sized companies, not necessarily our listed ones, these young entrepreneurs getting access to this money can only be good. And if the exit is something the PE asks for, you negotiate it, you get the best deal you can. That’s the price of the money.

Q: I also want to ask you about some of the big deals which are happening in the disinvestment landscape. What kind of legal bedrock is important to get these transactions done in your eyes? Because, on one hand, you try to sell a BPCL and on the other hand, you freeze retail prices of fuel for months leading to huge losses. Do you think some of this legal provisioning needs to be in place to be able to attract high quality bidders for some of the government assets?

A: The government was pretty smart in the Air India deal where we represented Tata. Ultimately, the government to my mind behaved like a private party transacting. So, if the entire debt burden would not have been taken over by a good bidder, they dealt with that. When it came to unions and employees, they dealt with that. So, I think the disinvestment arm of the government has finally figured that for the best value, they’ve got to offer an attractive deal. So, when you are talking about BPCL, if the losses continue and the deregulation issue and the pricing does not get resolved, the government is simply not going to get a good price.

Q: I also want to ask where you stand on this whole controversy brewing in Karnataka, with the high court upholding the ban on hijab in colleges. If you were part of this case, what would your contention be on a matter which has struck such a national chord?

A: My personal view is that religion is such a personal aspect of one’s daily life, that to intrude beyond a point is always counterproductive.

Any ill will is not as important as the feeling of security that you need in a population of this size. This has to be resolved in a way where communities don’t feel scared and think of leaving the country. They shouldn’t feel they aren’t part of the motherland. So, the Supreme Court will resolve it, I’m sure.

Q: Finally, having worked with so many top industrialists over the last couple of decades, if you were to single out one or two people who really struck you as men of impeccable integrity, who would those be?

A: My few interactions with Mr Ratan Tata have all been fantastic; always clear-headed and the constant refrain was always, what was the right thing we should do? I think that has been the DNA of the group for as long as I can remember.

There are other business houses which have been absolutely exciting to work with, just for their sheer intellectual brilliance and their execution capability. But I would still say that if I have a fondness for one group, it would be the House of Tata.