Sanjay Kapoor, CEO, Bharti Airtel Photo: Vivan Mehra/www.indiatodayimages.com

When he is feeling troubled,

Sanjay Kapoor allows himself a half-smile and talks of samosas. Not because the piquant snack, a health hazard as good as any, is comfort food for

Bharti Airtel's head of India and South Asia, but because it is at the centre of his favourite allegory. "In 2001 and 2002, a samosa cost 40 paise and a mobile phone call Rs 8 a minute. Now a samosa costs Rs 8 and a mobile call 40 paise a minute. It should never have happened."

During the good times, asking Kapoor a question is like flicking on a switch. His answers are comprehensive and spot on, just short of sounding rehearsed. But these days the half-smile and the samosa come up often because of the systematic dismantling of the telecommunications industry by a government desperate to repair its finances.

India became the world's

most competitive market for telecom when former telecom minister A. Raja issued a bunch of licences in 2008 - in the so-called 2G scam - taking the total number of mobile phone operators to 13. As an inevitable outcome, tariffs crashed. In the last three years alone, they have fallen 40 per cent. Alongside, the economy went into a slowdown, restricting consumers' willingness to pay and necessitating heavy discounts. As a result, the profit margins of every operator have crashed.

The first auction of spectrum, the airwaves that carry telephony services, proved to be a double-edged sword. In 2010, when the government called bids for spectrum in the 2,100 megahertz (MHz) band, which enables the data-intensive third generation (3G) services, only a small amount of it was on offer, creating an artificial scarcity. Spectrum-starved companies, which had to either have 3G in their bouquet of offerings or lose highpaying data users, bid the moon. The auction magically repaired the government's finances by netting Rs 67,000 crore but put the companies on a debt track that has placed a burden of nearly Rs 2 trillion on them (a trillion equals 100,000 crore).

This should have been a wake-up call. It was an encore of the European experience, where 3G auctions were held around the turn of the century. The bids were exorbitant and debt followed. Many of the winners struggled to survive and changed hands. The regulators, who in European countries are industry experts, not bureaucrats, learned their lesson and changed the system for allocating spectrum. In Sweden, for example, auctions are held as in India, but the bids there are amounts of investment the company will make. A commitment to cover all of the country is built into the contract. The singleminded intent is growth of telephony.

India remained sanguine. The government, unperturbed, approved in November a one-time fee on spectrum already held by operators. Operators were given 4.4 MHz to start services when the government opened the sector to private participation in 1994. In later years, they got more to ease network congestion. For spectrum beyond 4.4 MHz, they will have to pay for the remaining period of their licence. For everything above 6.2 MHz, they will have to pay retrospectively from July 2008.

Revenues from telecom can no longer be seen as a quick fix for India's fiscal deficit: Marten Pieters Photo: Shekhar Ghosh/www.indiatodayimages.com

The move will deal a blow of Rs 31,000 crore to the industry, which believes it is a second payment for the same spectrum since the operators have been paying for it over the years in the form of higher revenue shares. The government, however, wouldn't let go of the golden eggs, only now the goose is staring at death.

On November 15 Finance Minister P. Chidambaram called telecom a "stressed" sector. That was the day after the

auction for 2G spectrum closed and Chidambaram was not the only one in the grip of morose thoughts. The auction, which attracted bids worth Rs 9,400 crore - less than a fourth of what the government had put down in its calculations for this year's Budget - was not just a wake-up call; it was like being hit in the face with a wet slipper before daybreak. The auction was the result of the Supreme Court's February 2 order cancelling permits for circles allotted in 2008 in a questionable manner. It came with a high reserve price recommended by the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, which, in the wake of the 2G scandal, may have thought it better to err on the side of overestimation and avoid being accused of causing a loss to the exchequer.

The

auction was held over two working days either side of Diwali and turned out to be the fizzler of the festival season. Only five companies submitted bids, of which Bharti bid for just one slot - slots of 1.25 MHz were on offer - for only one circle, Assam. Many see this as a token move to make sure that no one saw the company as boycotting the auction. The bids by Idea, Videocon and Telenor were not a true indication of market interest either.

They were bidding to get their licences back. Only Vodafone, which bid in 14 circles, was looking to augment its spectrum bank. Naturally, the bids were feeble, and in many cases there were none at all. Four of the 22 circles, including the biggest markets of Delhi and Mumbai, received no bids. Of the 18 that did, only the bid for Bihar was above the reserve price, albeit only nine per cent above. The other 17 were won at the reserve price - not an indicator of an auction's success.

Even the Rs 9,400 crore that this auction netted will trickle in over time.

Winning bidders have the option of paying only a third up front and the rest in instalments over 10 years at nine per cent interest. For those whose licences had been cancelled, no payment may be necessary in the first three years since their 2008 payment will first be offset against the new licences.

The shortfall, Rs 30,600 crore, would have pushed the fiscal deficit, pegged at 5.1 per cent in this year's Budget, to more than 5.4 per cent if everything else remained unchanged. Except that many things have changed.

With slowing growth, low tax collections, and disinvestment far below target, the finance minister is already talking of a 5.3 per cent deficit, while Vijay Kelkar, who headed the 13th Finance Commission, says it could go up to 6.1 per cent.

Industry expects 50% of revenues to come from data by 2016

Revenues from telecom can no longer be seen as a quick fix for India's

fiscal deficit," says Vodafone's India head Marten Pieters. But the government is not done yet. It hopes to make up for some of the shortfall through the one-time fee on spectrum. And here we need to pause and look at the monster that has quietly crept up on the industry: a change in the government's attitude.

"The earlier model was of low upfront fees and an operator paid more as it grew. This model ran successfully with great benefit to the consumer and the economy. Now we have moved to a model of high upfront fees for spectrum, without diluting the payments to be made as one grew," says Himanshu Kapania, who runs Idea Cellular, the only telecom stock to trade higher than its last year's closing price.

The belief has gained ground that spectrum is a treasure trove, which can bestow untold riches on the operator. The operator, on its part, is there to absorb the higher cost and insulate the customer from the impact of the higher cost. This is untenable.

90% of the revenue in India comes from voice, despite the hype around data. The handset shift to 3G will take time: Sigve Brekke Photo: Shekhar Ghosh/www.indiatodayimages.com

"If the costs go up, they will have to be borne by the consumer and society," says Kapania.

And the economy, too. The government's change of model comes at a terrible cost. In the developed markets of Japan, South Korea, and Germany, telecom contributes up to 4.5 per cent to the GDP. India, on the other hand, is a paradox. The second largest market after China gets only 2.2 per cent of its GDP from telecom, a figure which is on the wane.

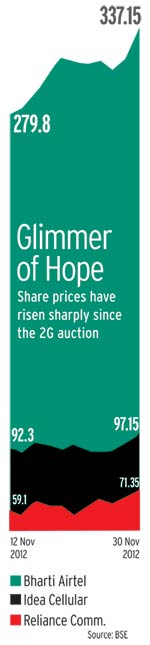

And yet, the auctions have not been without their silver lining. As bids whimpered, pleasurable echoes were heard far and wide. All telecom stocks except Idea Cellular had been 'underperforming' this year, that is, trading below their price of December 31 last year. They have begun to close the gap.

On the Bombay Stock Exchange, Bharti Airtel had gained 20.3 per cent by November 30, the day this article was finalised, compared to its price on the first day of the auction. Reliance Communications has shown similar gain. Idea, already the best performing, had gained 5.5 per cent.

The secret to this is far out. A bevy of research reports from investment banks say things look better because they cannot get worse, that the failed auctions have spared the companies crippling cash outflow, and that the fear that Reliance Industries will bid for the spectrum - presenting a new, formidable challenge to the incumbents - did not materialise after all.

On the Monday after the auction, Credit Suisse came out with a report titled 'The Turning Point'. It talked of a better future for telecom now that the auction was over and tariffs, among the lowest in the world, might go up. Bank of America Merrill Lynch, on the day after the auction ended, upgraded Bharti and Idea "on positive outcome of the 2G auction". Its verdict on policy decisions was telling. They "could be favourable hereon (unlikely to get worse at least) leading to potentially lower cash outflow from operators".

The government raised Rs 9,400 cr from the 2G auction

Telecom Secretary R. Chandrashekhar seeks to reinforce this conclusion. "Eighty to ninety per cent of the policy stabilisation process is over," he says. "The telecom industry has seen some very good days and then there were some bad times. But the best days are ahead."

Some of the operators, too, are daring to dream again. "We can get back to the golden era of post-2006 provided we correct the structural defects," says Airtel's Kapoor.

If costs go up, they will have to be borne by the consumer and society: Himanshu Kapania Photo: Nishikant Gamre/www.indiatodayimages.com

Sigve Brekke, who heads Telenor's India operations, goes a step beyond to say the company, which reclaimed six of its nine circles in the auction, will turn cash positive in 2013, that is, its revenues will exceed the operating cost. On November 29, Brekke's boss, global CEO Jon Fredrik Baksaas, announced that one of the company's circles, Uttar Pradesh East, had broken even in just three years. According to him this was the quickest breakeven for a circle in India. Next year, he hopes to make similar announcements for the other five.

However, that will take a lot more than just reclaiming circles and resuming services.

In 2009, when Tata DoCoMo started a price war with its new one-paisa-per-second scheme, Deepak Gulati, its head of GSM business thought it was the most innovative pricing the Indian telecom industry would see. That it may have been, but it was not the best for the industry's health. In fact, it was the beginning of the worst.

Soon every operator, 13 at that point, took to ultra-low tariffs. Not that they had an alternative, this being the most competitive market in the world. Free minutes and discount coupons rule. Ten to 11 per cent of customers switch operators every month. That is 80 million a year and more.

"It is like the industry is standing on quicksand. I'll be surprised if there are investors and shareholders who are not asking difficult questions to the CEOs about how they are going to be sustainable," says Kapoor.

Vodafone's Pieters agrees: "The current pricing levels are not going to support future growth and they have already hit the industry. We expect a situation where tariffs will go up." It is a principle Telenor agrees with - "We are nearer the bottom of the pricing curve than ever before," says Baksaas - but the reality may be a little different.

Tata DoCoMo may have started the tariffs' march to the rock bottom, but it was Uninor, Telenor's India brand, that pushed it along with its discounts to lure and keep customers. Its schemes, like two-paise-a-minute and five-rupees-a-day, ensured that it not only held on to its subscribers but also added new ones even after its licences had been cancelled.

"We always take the position where we are the cheapest. That is our value proposition," says Brekke. Ever the challenger, with no 3G spectrum to offer high-end data services, and now limited to just six circles, Uninor will be hard pressed to appeal to customers without talking tariff. Things may however begin to change with consolidation. Not strictly the M&A kind, which anyway becomes more difficult with the government saying the acquirer must pay separately for the spectrum.

"Consolidation always begins in the minds of consumers. Despite 13 players, the top four or five accounted for most of the market. The second is physical consolidation. Even before these auctions consolidation happened because of economic viability," says Kapoor.

Etisalat of the UAE and Bahrain Telecommunications, which had 42.7 per cent in S Tel, have already left. Some players shut down circles. Finally, during the auction, people for whom it was not making sense truncated their operations.

Sunil Mittal, Kapoor's boss and Bharti's Group Chairman, has often said that in the end there will be no more than half a dozen players standing. It may not happen soon on a pan-India basis, but it is already happening in each circle.

With reduced competition, and more control over tariffs as a result of it, data usage will be more likely to take off as operators will be able to charge for it without worrying too much about losing users. That will change the fortunes of the industry, since data users pay more and will boost return on investments. What's more, they stretch the peak usage hours. It is not uncommon for smartphone users, the main drivers of data usage, to be fiddling with their phones while their spouses snore.

80 to 90 per cent of the policy stabilisation process is over. The best days are ahead: R. Chandrashekhar Photo: Yashbant Negi

"Data is witnessing strong growth across the industry. We have over 32 million data users. Also the contribution of data revenue has gone up consistently. We have more than 2.1 million active 3G customers in India," says Pieters.

Airtel has put all its might into driving data usage. It recently opened a Network Experience Centre in Manesar, near Gurgaon, which has a 3,600-square-foot screen, the world's largest of its kind, showing minute details of what Airtel's users are up to, and the troubles they might be facing.

If a customer needs help with an Apple device or a Samsung Galaxy, Airtel is there to help. It monitors performance across devices. It watches the URLs customers go to and suggests those she might like to go to. It makes sure there are programmes at every stage to be accessed. "The moment we see a smart device latching on we make sure all the settings are in place for the customer to use efficiently. We make sure the customer has the best possible experience. Data is all about customer experience," says Kapoor.

Brekke - you guessed it - disagrees. "Ninety per cent of the revenue in India comes from voice, despite the hype around data. The handset shift to 3G will take time," he says. Kapania brings in the broad perspective. It was easy, he says, to grow voice in India. Indians always liked to talk; the phone gave them the opportunity to talk while being out of earshot. Data is trickier. It is a new need that customers need to feel. Besides, data needs an eco system of content, device, and service provider and has to be promoted by operators who do not provide the content.

But the trends are encouraging. All of Japan's mobile phone users are on 3G. Half of those in the US are data consumers. India will get there. Already one can see data's reach. Bal Thackeray's death brought Mumbai to a halt, but a stray comment in Palghar stirred the pot. That comment was made by someone using data.

Utpal Agarwal, a lawyer who was looking to change jobs in 2009, almost missed an interview when he did not check emails for two days. Never again, he swore, and acquired a BlackBerry. Now with law firm AZB & Partners, he clears 90 per cent of his email on the phone. The question is: will the government play ball? The portents are not great. And that could mean another round of disputes.

The one-time fee has already elicited a joint protest letter from Airtel, Idea and Vodafone to the Prime Minister. Signed by Kapoor, Kapania and Pieters, it says: "... there is no justification or legal basis for any unilateral imposition of any additional charges in the form of a one-time fee for spectrum held by operators which has been legitimately paid for in the form of higher revenue-share."

Next up is re-farming. The government plans to take efficient spectrum - in the 900 MHz band - from old operators, and redistribute it to level the field for newer operators. This spectrum requires less investment in infrastructure than that of the 1,800 MHz band and above.

The industry fears that Rs 25,000 crore worth of investment will be in jeopardy and fresh investments worth Rs 1 trillion required if the efficient spectrum is taken away and its holders fail to repurchase it. The point is that if the incumbents are allowed to repurchase the 900 MHz-band spectrum, the intent cannot be only to level the field. The money, as ever, is playing its role in deciding telecom regulation.

Someone in Airtel's Gurgaon headquarters, the building that glows in strips of red after sunset, will be talking some more about samosas.