Just two years ago, few outside Gujarat's Patan district had heard of the tiny village of Charanka. It is home to the tribal Ahir community at the eastern end of the great Kuchchh desert. Acres of wasteland owned by the community grows little except the occasional wild bushes.

One, no country in the world has set up 100 GW of solar capacity. Not even Germany - the biggest proponent of solar energy - whose capacity is 38 GW. Nowhere in the world has a country added 15 GW of solar capacity every year. "It is not an easy task by any means, but we are determined to make it happen," says Goyal.

That doesn't mean that a focused approach can't get India to the target. But consider what the Modi-Goyal duo is up against. It requires an investment of Rs 6.5 lakh crore (nearly three times India's defence budget) at a time when the Indian banking system is already laden with bad and doubtful debts of more than Rs 10 lakh crore. It requires 1,095 sq km of land (equivalent to 3,60,000 football grounds) when the country is embroiled in a raging debate over land acquisition rights. It requires 400 million units of solar modules when the country's solar module makers can manufacture only 70 million units in seven years. Though it's clean energy, it will still pose questions of viability as solar energy costs Rs 6 to Rs 7 per unit against the average cost of power of Rs4 per unit today. And, importantly, the new capacity will face the distribution and evacuation challenges that are the bane of India's power sector. "The evacuation and grid management is a big challenge, and if we look at expanding renewable resources the challenge becomes more steep," says Amit Kumar, Partner, Energy and Utilities, PwC India.

Indeed, at the end of the day, even if the target is achieved, it will only produce roughly 22,000 MW of power (solar panels work at 22 per cent efficiency) - that too in day time. That spike and ebb (at night) is another challenge India's grids may have to deal with whenever the capacity is up and running. Banmali Agarwala, CEO, GE South Asia, says the blend of renewable energy up to 20 per cent is manageable but beyond that this could destabilise the grid.

Lofty Ambition

It will be nothing short of a miracle if the Modi-Goyal combine achieves the target. As against India's ambition to set up 100 GW, the total solar power generation capacity in the world stands at 177 GW. While the global capacity has been set up over 15 years, India has set out to achieve its target in a short span of seven years. To stitch together India's solar story, Modi entrusted his additional principal secretary, P.K. Mishra, to help Goyal. Mishra is a confidant of Modi. He was chairman of Gujarat State Regulatory Commission for five years. His job is to take the bureaucracy along, and support 'out of the box' thinking in Goyal's ministry.

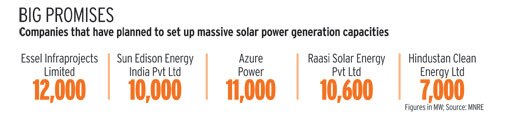

At a renewable energy conference in New Delhi in February, 200-odd Indian and foreign companies signed on letters of commitment to set up 266 GW of wind, solar and other renewable energy projects against India's current installed capacity of 230 GW. At least 166 GW of that was solar power commitment.

But there is a big question mark over whether the intent to humour India's prime minister and the power minister outweighed the intent to put such capacities on the ground. After all, SunEdison, which operates solar plants totaling 100 MW, committed 10,000 MW of solar and 5,200 MW of wind power plants. Axis Wind Energy, whose website is under construction, has committed 12,500 MW - the second-highest - of renewable energy. Interestingly, most announcements are in the form of MoUs and not concrete agreements.

Yet, such scale has never been achieved. As against India's annual target of 15,000 MW, the maximum annual capacity has been added by China at 12,000 MW in 2012. But nowhere near that since. In 2014, the US added the maximum 6,200 MW, its best ever. For the record, India has historically added around 1,000 MW per annum.

"These calculations are based on the improvement in technology and cell manufacturing cost reduction. But this (tariff reduction) can be done much faster, if the government intervenes by reducing interest rates, allowing dollar-denominated bonds, reduction in capital cost or introduction of other financial instruments," says Anurag Garg, Vice President of the solar business at Schneider Electric India. As solar cell technology has improved in terms of efficiency and economies of scale, solar power generation cost has fallen from Rs15 per kWh to Rs6-7 per kWh. Further improvement could bring it on a par with thermal power, which currently costs Rs4 per kWh.

Funding Blues

At a capital cost of Rs6.5 crore per MW, the cost of setting up 100,000 MW of solar plants works out to Rs 6.50 lakh crore. Even at a debt-to-equity ratio of 1:3, this will require debt to the tune of Rs 4.5 to Rs 5 lakh crore. Promoters will have to bring in funding of Rs 1.5 lakh crore. Another Rs 7-8 lakh crore is required for grid infrastructure and equipment manufacturing.

By all accounts, it's a big task. The government has yet to come up with a proposal for debt funding beyond the banking system. And the banking system has already hit the sectoral ceiling of 16 per cent for the power sector. Of the Rs 63 lakh crore of bank advances, more than Rs 9.5 lakh crore has been to the power sector.

Promoter equity will also not be easy to come by since corporate India's total debt of Rs 41 lakh crore limits promoters' elbow room. Foreign equity or debt investment is difficult because largely solar power generation continues to be a subsidised business. Goyal, however, informed Parliament that subsidies for rooftops have been reduced from 30 per cent to 15 per cent with the intention to eliminate them soon. "Risk capital is expensive. The nature of solar projects is such that once you mitigate the construction cost and get connected to the grid, you just have to do the right generation. This will create cash flow. This becomes an ideal situation for pension funds to come in and earn yields on annuity basis," says Puri of Hindustan Power. Besides, solar parks, even grid upgradation needs enormous funding. The Indian grid has an installed capacity of 260 GW. By 2022, it will be roughly 500 GW, needing an investment of Rs 43,000 crore by Power Grid Corporation. "Negotiations are going on with the Asian Development Bank (ADB), World Bank and state governments to stitch a soft loan," says a top official in the power ministry.

"The best way is dollar-denominated bonds, or government-backed green bonds," suggests Vineet Mittal, Vice Chairman, Welspun Renewables Energy Pvt. Ltd*. Goyal and Finance Minister Arun Jaitley are in talks to allow access to affordable international funds. Foreign funds are demanding stability in currency. One way is hedge fund pool, says a top official in the finance ministry. Pools ensure that the government will compensate for any depreciation in the currency. There is a market to hedge medium-term foreign exchange risk, but it is 'expensive' as foreign funds see the life of a solar plant at roughly 25 years and are pushing to mitigate risks, says the official. The biggest drawback is that international funds prefer equipment sourced from established international players. And that's not in sync with Modi's 'Make in India' promise as solar is one of the 28 items listed for local manufacturing under the initiative.

Land Blues

Charanka-like farms with roughly 20 GW capacity will require at least 324 sq km of additional land. The Wasteland Atlas of India says that India has 4,70,770 sq km of wasteland, and that the planners have considered just three per cent of this for roughly 400 GW in the country. But that is in theory. "Availability of land at a suitable price is an issue. The land acquisition bill has already increased the compensation amount to four times. This will limit the area that can be brought under the solar energy," says the CEO of a power company. "Tamil Nadu has the best solar policy, but it is unable to attract investments. It is only because land is not available at a suitable price," he added.

The Saffron State Push

During his campaign for the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, Modi inaugurated Welspun's Neemuch solar plant, and called it saffron revolution - taking a leaf from the green revolution four decades ago. As the PM, he now hopes to take all saffron states along. Since May, states have, for the first time, issued tenders to set up 6,000 MW of new solar plants.

Other than this, these states are aggressively pushing environment and other clearances. Madhya Pradesh's state agencies are working to start 2,000 MW of solar farms at Rewa, Neemuch and Agar on about 28 hectares of wasteland. "We are committed to providing round-the-clock good quality electricity to every citizen in the state. Solar and wind energy play a critical role in providing access to those living in remote areas of the state," Chief Minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan had told BT in an earlier interview.

"We understand this issue. Most of our projects are in plug-and-play mode. Agencies from the Centre or states or their joint ventures, are developing them, and later we can get equity partners from the private sector," says Upendra Tripathy, Secretary, MNRE.

In Rajasthan, also run by the BJP, Chief Minister Vasundhara Raje Scindia is busy attracting investments. Rajasthan has installed capacity of 868 MW while projects of 829 MW are under implementation. Rajasthan receives maximum solar intensity in the country and has low precipitation, while there are long stretches of land available to set up plants. The state is now looking at bigger projects of 100 MW and above.

In October last year, Rajasthan revised its Solar Energy Policy, 2014. It allowed projects to use agriculture land without land use change. This resulted in proposals and joint ventures of 32,000 MW from corporate houses such as Adani Enterprises, Reliance Power, IL&FS, Essel Infra, Azure Power and US-based SunEdison. Rajasthan Solar Park Development, a state government subsidiary, is developing two solar parks of 1,400 MW at Bhadla and 1,000 MW in Jaisalmer.

"We have tried to interweave these (initiatives) to create a progressive, farmer- and industry-friendly policy. The state is fast emerging as one of the largest solar hubs of the country," Scindia told BT.

In fact, Chandrababu Naidu, the BJP's ally in the National Democratic Alliance, was the quickest among the chief ministers to get an in-principle nod for two solar parks in Kadapa (1,500 MW) and Kurnool (1,000 MW) districts of Andhra Pradesh on November 28, last year. Kadapa would be the country's largest solar park. The total installed capacity in Andhra Pradesh is 250 MW; the target is to take it to 5,000 MW in the next few years.

Equipment Conundrum

At 2.5 GW per annum, India's solar module manufacturing capacity is woefully inadequate to meet the annual demand for 15 GW. At the same time, India has mandated use of locally manufactured solar cells for 3,000 MW installations (where developers have sought subsidies). The US has challenged these norms at the World Trade Organization.

"India doesn't have manufacturing capacity to cater to this need. Neither do domestic players have access to capital to scale up their operations rapidly. There is a huge challenge for the government to help them scale up the capacity. One of the ways is to assure them off-take," says Kumar of PwC.

Viability Gap

Unfortunately, most state-run distribution companies - which will eventually buy the more expensive solar power - are in no financial condition to absorb the higher costs. So far, lack of political will has prevented state governments from charging higher rates from consumers. In India, 21 out of 29 state distribution companies are incurring losses. Rajasthan, the state most aggressive in solar power capacities, has a debt burden of a whopping Rs77,453 crore with accumulated losses of almost Rs 6,000 crore. Madhya Pradesh is about Rs 10,000 crore and Rs 5,246 crore, respectively.

Anil Sardana, CEO of Tata Power, remains circumspect. He says the big challenge is creditworthy off-take of power. "The financial health of many distribution companies is poor, causing delays in payment for the power they procure," he adds. Tata Power has 54 MW of installed solar capacity in India, and is expanding its presence in Rajasthan.

Arundhati Bhattacharya Chairperson, State Bank of India, during a discussion on Financing Renewable Energy at the recently concluded Re-Invest, shared her concern about the health of distribution companies, and feared they may refuse to use renewable if it continues to be unviable.

The buck stops here, says, Sujoy Ghosh, CEO of US-based First Solar's India chapter. His company is the world's biggest panel manufacturer and is developing 200 MW capacity in Andhra Pradesh and Telengana. "If the power purchase agreement (PPA) becomes stable and bankable, it will not only make investments viable but will also give confidence to the ecosystem," he says. Today, investors are looking at the off-take surety. Arup Roy Choudhury, Chairman and Managing Director of NTPC, says he will only set up solar plants if state distribution companies assure to buy power at a 'sustainable' tariff.

One option is to bridge the viability gap by issuing tradable renewable energy certificates (RECs) that are bought by polluting industries to meet their carbon reduction commitments. However, REC trading has flopped in India. In 2014/15, the MNRE issued roughly 96 lakh certificates, but only 30.6 lakh could be traded. Out of this, roughly 10 lakh were from solar players alone, though only 39,000 were traded, that too at the floor price. "The health of distribution companies is not great, and most of them don't honour renewable purchase obligations," says Rahul Gupta, Director of Rays Experts, a firm setting up plants in Rajasthan.

Tackling Tariff

One of the biggest challenges Goyal faces is in bringing solar tariff at parity with the grid. New solar units produce power at roughly Rs 6.5 per unit. In comparison, coal based plants produce power at Rs 3 to Rs 4 per unit. This makes solar plants unviable until the government provides subsidies.

The amendments in the Electricity Act, 2003 pending in Parliament mandate thermal generators to add a certain percentage of new capacity from renewable resources. Most of these generators are public-sector companies, and once these amendments become law, these can be pushed ahead. This will allow big thermal companies such as Tata Power, Adani Power, Reliance Power, NTPC, and JSW Energy to leverage their balance sheets and asset base for cheaper debt (they will get a better rating from credit agencies).

In February, NTPC was asked to set up 15,000 MW of solar power capacity. "The government may also ask other profit-making PSUs, such as Coal India and SAIL to invest in solar, adding up to around five to six GW," says a senior RSS leader, actively working in the energy sector. It remains to be seen how their shareholders react as power generation is not their core business. "But they do consume electricity," the leader countered.

In the budget session, Power Minister Goyal clarified that the ministry is not looking for subsidy-based solutions. Mishra and Goyal also pushed other bureaucrats to look for plan B, C and beyond. "All we want is to reduce the tariff by another Rs1," says secretary Tripathy. Solar projects have four cost elements - cost of money, cost of capital, cost of operations and cost of dispatch. The idea is to reduce the cost of money. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) recently reduced the repo rate by 50 basis points but that's not good enough. Currently, Power Finance Corporation, Rural Electrification Corporation, IFCI and Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency are lending at 12.5 per cent to 13.5 per cent. "At this rate it is difficult to make projects viable," says Mittal of Welspun.

The other idea being debated is bundling expensive solar tariff with the cheaper thermal tariff to arrive at a weighted average tariff. There is roughly 48,000 MW capacity in the country (thermal and hydel) which may retire by 2022, and a majority of this has a tariff of less than one rupee per unit. However, power ministry bureaucrats may puncture this idea. They prefer all ageing plants be refurbished with the supercritical technology to retain their coal linkage, which would be more lucrative, but would increase tariff.

"Our experience around the world says that once the commodity (electricity) comes down it expands the market size," says Ghosh. The Rs 17 a unit tariff saw 50 MW a year addition, and today we are seeing roughly 2,000 MW a year with Rs 6.5 a unit, he adds.

Meanwhile, at Charanka, the stream of visitors hasn't ebbed since the park was opened. The village now hosts 6,000-odd tourists annually, just to see the farm. A recent high-profile visitor was Bhutan's Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay in January. Whether the Modi-Goyal duo achieve their target or not, any number of solar parks that will be set up around the country will definitely provide local employment to the likes of Hitesh. And if they also become tourist destinations like Charanka, who would complain if India achieves even a fourth of its target?

Glossary

Explanation of key terms

REC: A renewable energy certifi -cate is issued to the operator of a renewable energy unit. This can be traded at the exchanges.

RPO: Renewable procurement obligation is a must for distribution companies to buy renewable energy on a predetermined target. This is meant to give renewable energy a push. It also allows discoms to move towards a green energy blend.

RGO: It stands for renewable generation obligation. The government is making it compulsory for thermal power companies to add renewable resources in their portfolio.

FEED-IN-TARIFF: In this a separate bid is not required for allocation. The promoter can plan power units anytime of the year, and can supply to their consumer as per conditions of PPA and grid rules.

PV: Photovoltaic modules convert solar energy into electricity using semiconductors. The photovoltaic method creates electric current or voltage, upon exposure to light.

OPEN ACCESS: This is a grid management tool that allows generation companies to directly sell electricity to the consumer. VGF: Viability Gap Funding is a fi nance tool where a state determines the tariff and assures that the gap will be funded by the state's resources.

BUNDLING: This is a new formula the government is developing where certain unscheduled units from thermal and hydel plants with cheaper tariff will be bundled with expensive solar before it is offered to the discoms.

(*The print version of this story had mentioned the incorrect designation of Welspun Renewables' Vineet Mittal. It has now been corrected. We regret the error.)