During a recent visit to Delhi, 17-year-old Sunny Vohra from Punjab’s Guru Har Sahai in Ferozepur district, was fascinated by the smartphones his cousins were gaming on. Once back home, he couldn’t find the brand in any store; calling up stores in Chandigarh—nearly 230 km away—didn’t help. Finally, he called up his Delhi-based cousin to find out where to buy the phone. His cousin shared a few links; Vohra went online, and a slew of brands on e-commerce platforms—some of which he had never heard of—serenaded him with options. While he had been searching for a POCO phone, he bought one from iQOO, a brand he hadn’t heard of earlier, based on the positive reviews on the platform. The phone arrived, he unboxed it and found a charger with the vivo branding. That’s when he realised iQOO was from the familiar Chinese company’s stable. And many of his friends use vivo phones, which have responsive after-sales service.

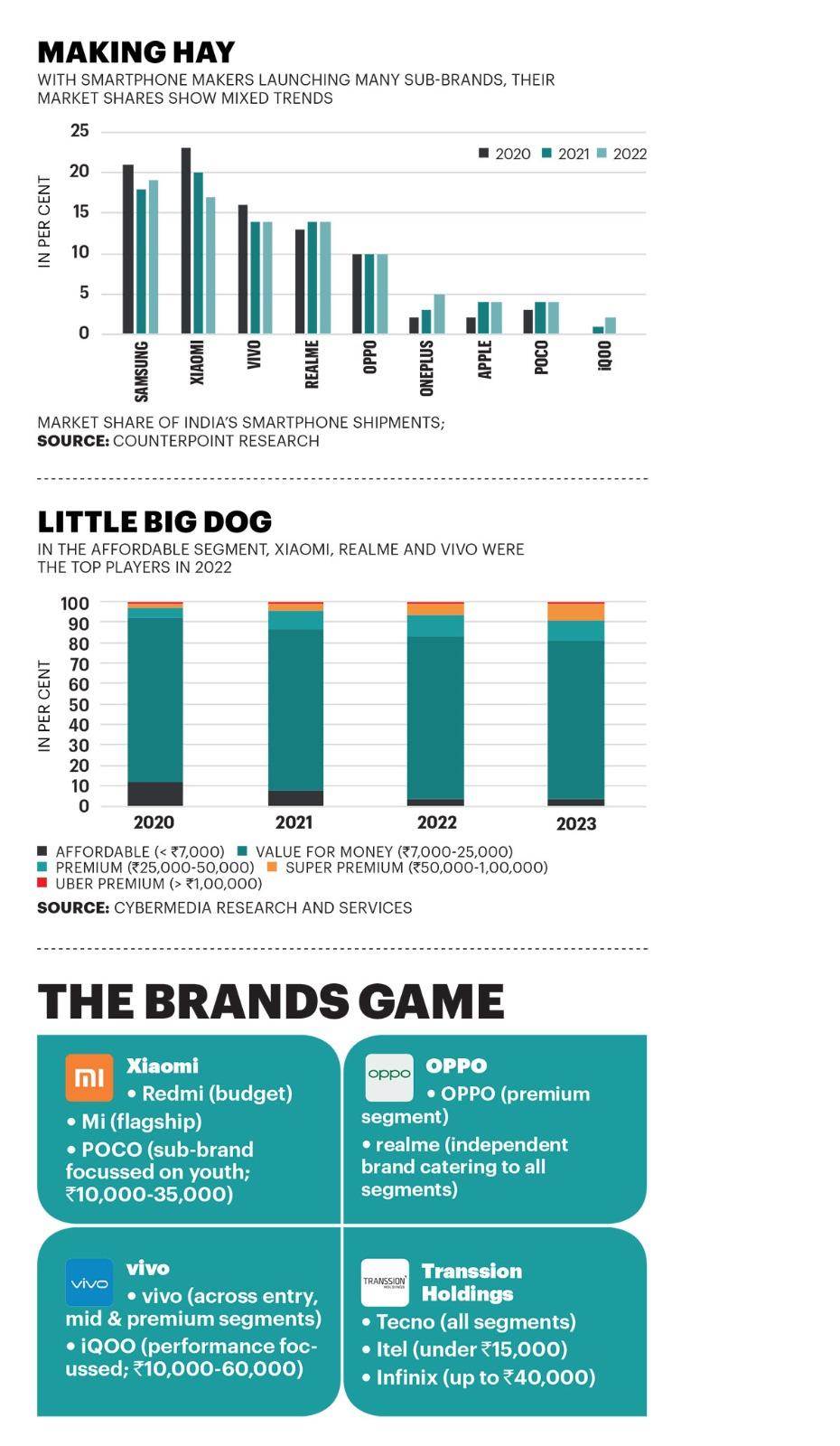

Chinese smartphone firms have been wooing the Indian consumer for quite some time. Now, they have upped their game by launching phones packed with features like never before, but with separate branding, and at prices lesser than the bigger brands. You want a camera phone? I got one. You want one for gaming? I got one. You want long battery life? I got one. And customers are lapping them up. According to data from Counterpoint Research, second brands have steadily grown their market share in the past few years. In fact, realme—a brand from the OPPO stable—has surpassed the market share of the mother brand.

Wooing Customers

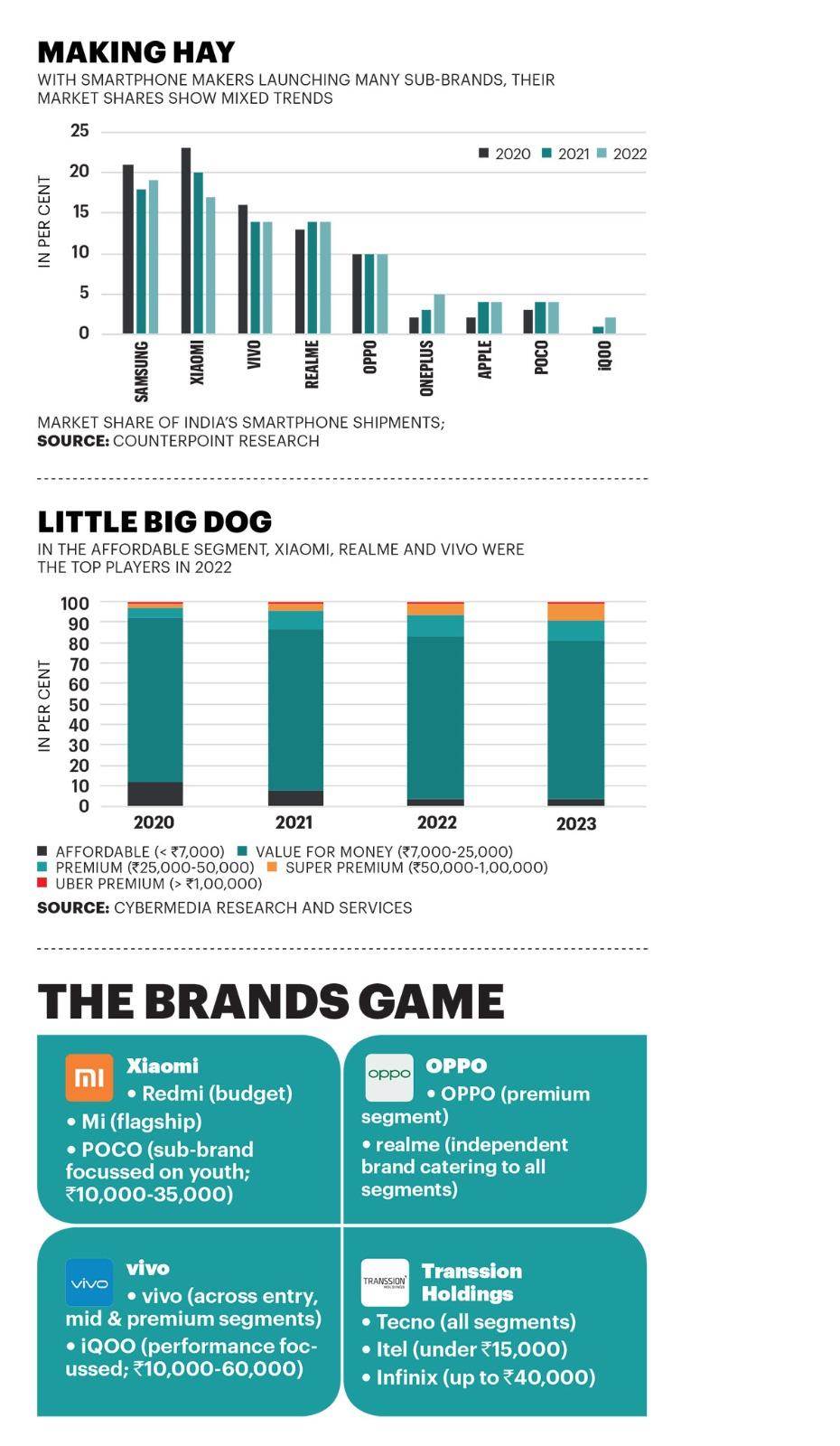

The Indian consumer, too, isn’t buying their first smartphone. Now, they want more features, and are willing to stretch their budgets for that. Earlier, most smartphones sold in India would cost less than $200, says independent technology analyst Satish Meena. And while the price-sensitive buyer is ready to spend more, “they are not willing to pay the same price, as say a Samsung or Apple, to the Chinese manufacturers”, he says, adding that these companies are creating sub-brands or second brands to cater to customers moving up the value chain.

For instance, Xiaomi, which dominated the sub-Rs 20,000 segment since coming to India in 2014, struggled to make a mark in the Rs 25,000-plus price band, which was then dominated by OnePlus. To counter this, it launched a sub-brand called POCO in 2018. Similarly, OPPO, popular in the Rs 30,000-plus segment, didn’t make much headway in the sub-Rs 20,000 category, where Xiaomi’s Redmi line dominated. To target this space, OPPO came up with realme. Unlike POCO, realme functions as an independent entity and a brand. Likewise, performance-specific iQOO was birthed when vivo decided to cater to the GenZ and youth.

Customers are willing to spend more on better smartphones also because their replacement cycle, which used to be 12-18 months earlier, is three years now, says Meena. “So now, they are looking for brands that can give them a device that can last that long.” Also, according to Chandrashekhar Mantha, Partner at Deloitte India, the Chinese smartphone firms are trying to create aspirational value for customers with their second brands. “India is a price-sensitive market, and when you go down the price bands into budget segments, the brand loyalty becomes low,” says Prachir Singh, Senior Research Analyst at Counterpoint. Therefore, it’s necessary to create an aspirational brand. “You can introduce a lot more products that will enable creation of a product and engagement ecosystem, which will then come under the premium category,” says Mantha. Is building an ecosystem the longer game then for these Chinese smartphone makers? More on that later.

Giving them what they want

“The sub-brand strategy is basically a way for them to target new segments of consumers... Segmentation has long been a strategy in consumer goods, for example, from companies like Procter & Gamble or Coca-Cola. Smartphone brands realised that as smartphones themselves became less about the technology and more like commodities, they had to follow suit,” says marketing veteran Alex MacGregor, who has worked with brands such as Meizu, OPPO and OnePlus.

Nipun Marya, CEO of iQOO, says the most important way to segment the market is by user needs. Catering to specific demands is the reason for this upsurge. vivo, for instance, realised this trend three years ago when it launched iQOO in 2020. “There are different segments in the market, and you cannot really stretch beyond your [brand] positioning because the whole crux of the brand is that you have to stand for something. vivo stands for the camera... We felt there was a gap, because many people today look for the best multitasking experience and the best gaming experience. And this is where we think iQOO is very well positioned, to serve this performance-hungry consumer,” says Marya, adding that even the target audience of the brands is very different—while iQOO targets 20–25-year-olds, vivo focusses on 26-27-year-olds.

It’s not easy, though. POCO’s first device, the F1, disrupted the market. But customers had to wait for two years for its next device, as it’s not possible to create disruptors all the time. And that led to a gap of two years where POCO could not leverage the legacy of F1. Himanshu Tandon, Country Head of POCO India, says that while the product was good, the company did not have enough products in the pipeline to sustain the brand. “That was the mistake we made... waiting for the next perfect product.”

Customer preferences aren’t restricted to just features, says Marya. Unlike earlier when offline retail dominated, many consumers prefer online channels. Online is also a good way to make the product accessible. “If your price point is low, the distribution has to be cheaper, because your margins have to be managed. Hence, it’s important to have a very strong online play,” says Deloitte’s Mantha, adding that online is critical to achieve scale. For offline play, companies need to have a strong mother brand. Plus, they also need to be premium. For instance, say industry observers, brands such as Apple, Samsung or OnePlus have dedicated stores.

Why don’t an Apple or a Samsung need to create sub-brands? That’s because their brand positioning is so strong that customers buy their phones just because they are made by them, say industry watchers. And is such a strategy utilised only in India? Not really, but nowhere is it possibly as prolific as in India, say experts. In developed markets, Apple and Samsung, for all practical purposes, have a duopoly and there aren’t as many price points to cater to as in India. But this strategy could work in a market similar to India’s, say industry watchers.

Core Synergy

The sub-brand or second brand concept isn’t new; it has been used extensively in the FMCG space. There are two ways of doing it—one is called a branded house strategy; the other is called the house of brands strategy, where you have multiple brands in a company. For instance, in the FMCG space, Unilever has multiple brands—such as Dove and Lifebuoy, which are separate brands within the same company. In a branded house strategy, the mother brand is omnipresent. For instance, the Tata group that has Tata Salt, Tata Tea and even Tata Motors. Marya of iQOO, says smartphone makers do things a bit differently. “Wherever we think there is background synergy possible, we try to utilise that synergy, and wherever we think the two brands need to be distinct, the brands are distinct,” he says, adding that it is always beneficial to have synergy for R&D, manufacturing and after-sales service, like iQOO and vivo do. Similar is the case with POCO. But on the front end, “our sales team, planning team and marketing team are different,” adds Tandon.

Incidentally, OnePlus—that integrated with OPPO globally in 2021—uses the back-end synergies of the latter. But it has a distinct identity. “OnePlus was able to build a large business on the back of identifying the tech enthusiast crowd and focussing on this niche with their product and marketing in India. Even though there have been many changes, they’ve still managed to cultivate a huge following and the brand is widely regarded as one of the best in the market, which in turn commands premium prices and likely profits,” says MacGregor. OPPO’s other brand realme, launched as an independent brand and legal entity, uses only the mother brand’s facilities to manufacture its products.The Ecosystem Play

While these brands were introduced with a specific target audience in mind, market acceptance has led to them offering smartphones across price bands. That, say experts, is to ensure that the brand has an offering as a customer moves up her smartphone journey.

With some of these brands being present in price bands similar to their mother brands, isn’t there a chance of cannibalisation? Mantha says a little bit of cannibalisation might happen “but at the core of that target segment, there is very limited play because it’s completely focussed on a different set of customers”.

But it is the diversification beyond smartphones—into IoT devices, laptops or televisions—that seems to be the long game. For instance, realme has a portfolio of products across flagship smartphones, wearables, laptops, tablets and TVs. Similarly, Infinix Mobile, part of China-based Transsion Holdings (that also has brands like Tecno and itel), has smart TVs, audio accessories, laptops and more. “For most sub-brands, the transition into multiple categories will happen going forward. This is a part of the overall ecosystem strategy, which brands are adopting in the overall smart ecosystem, and not just smartphones,” says Counterpoint’s Singh.

And lest we forget, Apple, Samsung and now OnePlus have well-defined ecosystems. “You need to create an ecosystem wherein you have your consumers on the same platform using various products and services. It can take the shape of a loyal community and further strengthen the brand,” says Mantha, adding that marketing communications can be channelised with the rich consumer behaviour data and one can also retain customers for a longer time. “It can also help you to understand trends, expectations and preferences that become key inputs to your product strategy. So, creating an ecosystem is possibly going to be the way forward,” he says.

Whatever be the strategy, what this means for customers is more choice and better products at reasonable prices. Companies, too, will be aware of customer preferences and design products that are winners. A win-win for all, don’t you think?

@nidhisingal, @abhik_sen